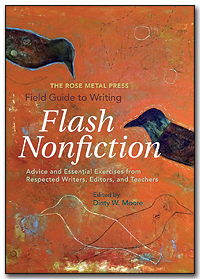

The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Nonfiction: Advice and Essential Exercises from Respected Writers, Editors, and Teachers, edited by Dinty W. Moore. Rose Metal Press, 2012.$15.95, 180 pages.

The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Nonfiction is the first book-length discussion of this increasingly popular form, and the third in the publisher’s series of craft guides. Twenty-six essays deconstruct various aspects of writing narrative nonfiction in the very short form. Contributors offer practical exercises while exemplifying their personal approach at execution—at times clearly, particularly for the more experienced, though occasionally leaving the new writer hungering for more instruction.

Across the spectrum of notable essayists, contributors include Robin Hemley, Judith Kitchen, Eric LeMay, Lee Martin, and Sue William Silverman. Editor Dinty W. Moore offers an introduction and history of the genre, accounting for both international influences and contemporary evolutions made here in America. In part, Moore credits the “energy and activity” of flash fiction for the rise of its nonfiction counterpart and admits both have capitalized on the short form’s suitability for digital venues.

What this craft guide does well is in refraining from pigeon-holing the genre by suggesting strict guidelines or definitions. Yet in freedom there remains the challenge for writers to experiment and tinker—not always for the better. After all, what is “good” flash nonfiction? In his introduction, Moore addresses the one quality that appeals to both editors and readers: “the writer’s experience of the world made small and large at the same time.” Yet how many words does that take? Two hundred? Five hundred? A thousand?

Contributor Barrie Jean Borich discusses the challenge of writing to such a limited word count: “Most short shorts are not written in a flash. If we are essayists, our first instinct may be to keep adding more, making more connections, applying yet another angle on metaphor.” The challenge, she argues, is in working at length to tighten, trim, and fine-tune the work to its “decisive moment”—to find the precise subject that can be addressed in a flash of a moment.

Where the emerging writer may need more guidance is in the shaping of beginnings and endings. Although the prompts provide opportunity to explore a “decisive moment” and precise subject in a limited narration, there is not much time spent on acknowledging that a flash story—nonfiction inclusive—still must have something of an arc. As readers of flash, we expect a hook in the opening and a resolve in the conclusion that leaves us satisfied; yet the challenge of fitting in these elements within a very short piece can be overwhelming for a new writer. While the contributor essays demonstrate a taste of how structure is approached, there is little discussion about how those decisions were made and what choices authors may consider.

Brenda Miller touches on the beginning and ending lines in her essay, “Swerve,” which mirror one another and fulfill what she describes as “the same attention to language as one would give to a poem.” Anne Panning suggests that “in flash nonfiction, the opening is not as rigidly fixed as it is in flash fiction” in that it needn’t “begin in medias res the way short fiction does.” Yet, how does one determine what a suitable entry point is and how does one wrap a story around to conclusion in flash nonfiction?

In fact, what is the difference between flash fiction and flash nonfiction. The latter is ostensibly based on the “truth.” But truth is suspect: no memory is “true” exactly to the events that happen. Storytelling by definition is fiction, even if it is labeled “nonfiction.” That said, it’s the categorization of a text as nonfiction or as fiction that shapes how the reader experiences the piece. In the nonfiction writing world there is at least an ethical obligation on the part of the writer to recall events to the best of the writer’s knowledge. In other words, the best definition of nonfiction writing is not that it’s “true” but that it consciously avoids trying to be false.

In her contribution, for example, Peggy Shumaker speaks to one piece where she “chose deliberately to leave the scene unresolved,” suggesting this approach may bring “energy” to the piece. “Unresolution” may bring energy but it also perhaps doesn’t include the entire truth. Such approach appears elsewhere, as when Maggie McKnight discusses how framing works to “shape” a brief narrative.

Jenny Boully’s contribution, “On Beginnings and Endings,” addresses why she “adore[s] beginnings” and why she “fear[s] endings with the same intensity.” But for the writer seeking advice on how, exactly, to execute such integral parts of storytelling, there is a bit of disappointment in this guide for its lack of direct address on the matter. As Moore says in his introduction, we need the large world contained within the small—but it’s the execution of how to do so that many writers new to the genre will find frustrating.

The collection does, however, provide tips for dissecting the heart of a nonfiction story. As an example, Rigoberto González contemplates the split second between memory and the memory-trigger, isolating how to use image as a larger representation. In the essay “Writing in Place,” Bret Lott urges writers to consider their “matter of life and death” selections to fit in the “absolutely compressed form.” These are valid considerations for the writer of any essay, yet the guide zeros in on how these elements are even more critical in the short form.

With the rise in popularity of flash nonfiction, this Field Guide demonstrates how and why the genre is so inviting to both writers and readers: this is a form well-suited for experimentation and hybridization. Contributors provide examples of flexibility within condensed memoir and essays and, though practical instruction is offered that the more advanced will find useful, writers new to the flash form may wish to consult titles listed in the “Further Reading” appendix to gain an even broader sense of structure.