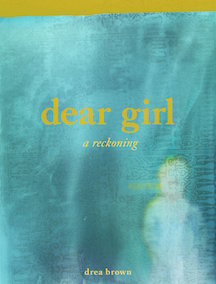

dear girl: a reckoning, by Drea Brown. Gold Line Press, 2015. $10, 48 pages.

Whose silken fetters all the senses bind

—Phillis Wheatley (from “On Imagination”)

Drea Brown’s chapbook, dear girl: a reckoning, renders a vivid, wracked, and delirious rewriting of Phillis Wheatley’s transatlantic journey in the hold of a slave ship. This is a collection that seeks to explore the haunted, the scuttled, the bound, and the broken histories evoked by the Middle Passage. In remembering Wheatley’s trip from West Africa, aboard the schooner, Phillis, to Boston, where she was sold into captivity, Brown articulates the legacy of slavery and racism in the United States as an ongoing trauma, as a series of violent dislocations that have become embedded in the DNA of American identity. Brown’s collection begins and ends with poems announcing that: “the dead will have their due.” The dead will have their due because: “they will speak from graves or whisper into the ears of poets who search oceans, to begin here with rupture or capture or loss.” Loss provides a point of departure for Brown: the loss of homeland, the loss of freedom, the loss of self, the loss of life. These accrue in the black body as it crosses the Atlantic, steering the narrative of dear girl. Brown’s reckoning begins when she incarnates “the phantom limbs of cultural memory,” excavates “tombs of historical trauma,” and queries “what the body or the spirit stores and aches to release.”

In dear girl, bodies dissolve and reappear, forever shrouded in the darkness of cargo and coffins. The darkness that haunts these poems opens a space where a dialogue between the ghosts who perished during the Middle Passage might speak to the descendants of their kin. The space where “eyes become eyes in the dark” is also the space where historical gaps might be bridged. The restructuring of this space in Brown’s narrative provides hope. Brown writes:

for a moment reader allow me to reach

further into the water to find something akin to

mercy or salvation.

By returning obsessively to the churning waters that robbed Wheatley of her freedom, Brown explores the complicated heritage of the poet’s work. Wheatley herself glossed over the agonies she suffered during the Middle Passage in her poem “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” which reads:

Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

Brown’s chapbook provides a compelling rejoinder to this poem, which is problematic despite its affirmative ending. Brown’s prose poem, “phillis land-ho!,” grapples intensely with the complications that come from being renamed after a “sarcophagus at sea.” The poem ends:

phillis whose name meant slave and sounded like sorrow song. nothing about her was her own. name body tongue god. how to become this new thing when you have already learned you are human?

For Brown, Wheatley’s importance dwells not in her embrace of the Christian God, but in her resistance to the “scornful eye” that castigated her “sable race.”

dear girl: a reckoning continues the tradition of resistance through writing embodied by Phillis Wheatley. Drea Brown’s writing joins the ongoing conversation about the legacy of slavery participated in by Robert Hayden, Nathaniel Mackey, Amiri Baraka, Paul Gilroy, Toni Morrison and many others. This collection of poetry is cyclonic in its re-envisioning of historical trauma. Brown’s formal and experimental control ensure that the ever widening gyre of this poetry holds fast. The center that holds here revolves in motions of renewal and avowal. Brown implicitly hopes we might begin to come to a reckoning with who we are, if we have the courage to conjure and confront the “marvelous horrors of past-not-passed / tenebrous and fleshly thunderous things.” That Phillis Wheatley never escaped the “past-not-passed” of her transatlantic ordeal is nowhere more evident than when she speaks of the imagination in the language of her bondage. Silken fetters remain silken fetters, with sharks following. Drea Brown chums the waves with these luminous poems of witness. In these waters, the dead might rise again and we might come a little closer to the sharp teeth of “tenebrous and fleshly thunderous things.”