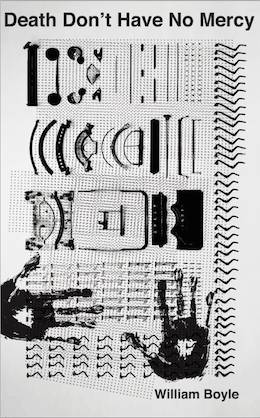

Death Don’t Have No Mercy, by William Boyle. Broken River Books, 2015. $15. 194 pages.

William Boyle, author of the new short story collection Death Don’t Have No Mercy, has ideas about crime. Moreover, he has ideas about crime fiction. His gritty stories are peopled with hopeless drunks, losing boxers, fuck-up thieves, and more than one remorseless psychopath. At the same time, they’re the kind of stories where, just as you’re thinking, “Hey, this scenario is sort of similar to ‘The Killers,’” one character says to another, “It’s like that Hemingway story ‘The Killers.’” In one, an unpublished writer caves in his no-good brother’s skull with a typewriter. There’s nothing coy or meta about it, but Boyle’s consciousness of his writing’s place in literature shows through.

So, what about crime? Why read about it? It might be because you’re curious, like Calhoun, the protagonist of the title story. The tale opens with him wondering why he, a middle-aged barfly, has stolen a Walkman from a neighborhood kid. Whatever the reason, he’s delighted to find that the tape inside plays classic country and blues. Calhoun wanders through his routine, wondering about the rightful owner, a Black preteen in the Bronx who chooses Hank Williams and Memphis Minnie as the soundtrack of his life. Meanwhile, the readers wonder about Calhoun.

This is crime-as-education, crime as life-affirming-leap-over-the-walls. It’s one of the things crime fiction can offer its readers: a chance to go everywhere, to look at and listen to what we’re told to ignore, to get out from under the Law’s inevitable oppressions for a minute. This is all pretty much harmless. Calhoun even tries to return the Walkman after he’s copied the tape.

Then the story ends with violence that has nothing to do with Calhoun’s precious little larceny. If you’ve been reading for any of the reasons I just wrote about, it’s a sickening turn, a repudiation: no, crime’s not for the curious. Crime is ugly, incomprehensible nonsense. Crime kills and confines. It never frees. You read about it because you’re probably a bit of a monster yourself, and you like seeing nasty stuff happen to people—another thing crime fiction offers its readers.

That’s the first story. Boyle spends the rest of the book elaborating these ideas. In “Poor Box,” a drunk called Angelo first tries to steal donations from his mother’s Brooklyn church, then gets himself in trouble cadging drinks from gangsters. About to be shot, he’s seized by the need to confess his sins. By the grace of God, he escapes and flees to Manhattan, where he’s taken in by a priest.

So far, so good: it looks like we’re reading an epiphany story, with a character jarred into a changed self by his brush with death and disaster. But that isn’t how things end up. Angelo steals the priest’s jacket and wallet, then buys a bottle of wine and a ticket upstate; “Poor Box” proves to be about a guy who first fails to rob the Church for booze money, undergoes some trouble, then succeeds and gets his drink.

Similarly, in “Poughkeepsie,” after a burglary goes bad, a small-time crook hides from the cops on the roof of an apartment building, where he conducts a tortured review of his life beneath a full moon. The morning after, he climbs down, robs an old lady, and drives off to uncertain freedom in her car. The characters in these stories are trapped in their own identities, the reader trapped with them. Crime doesn’t lead to change or enlightenment, only back into the criminal self.

A parallel dynamic is at work in “Far From God,” in which a gunman who should be lying low is convinced to run off with a woman he’s just met, and “Here Come The Bells,” in which a well-meaning dude gets wrapped up with a crime boss’s underground-boxing-and-debt-collection business in order to pay an ex-girlfriend’s medical bills. Both stories come to impressively bloody ends. What’s interesting is that they both get there by means of their central characters’ breaks with reality. These guys start out normal enough, but they end up murderously nuts.

Boyle defies the convolutions of plot and counter-plot that crime and suspense stories often rely on. The action begins with concealed motives, threatened betrayals, entrapment—all hallmarks of the crime plot—but ends with unmoored violence that responds less to those things than to the characters’ own insanity or paranoia. Once again, we’re presented with one version of crime—call it crime-as-compelling-chain-of-events—only to have it snatched away and replaced with another version—call it crime-as-eruption-of-fucked-up-character.

All of these stories take place within a pretty limited radius, centered on New York City. We visit the Bronx, Coney Island, some other seedy parts of Brooklyn, the rundown towns of downstate. Here young men live in basements alongside their mothers’ old pianos. Barflies stop by the local in the morning to get whiskey poured into Styrofoam coffee cups. Italian fathers make their own wine, and when characters get something for free, they get it “on the arm,” an expression I had to look up. Boyle’s characters imagine escaping, but Montreal is as far as their imaginations will take them, the edge of their known world. I’m tempted to call the picture he paints “accurate,” but I’d have to know the locale much better to make that judgment.

This is a man’s world. In eight stories there are eight male protagonists. Women mostly enter these narratives as victims, sex partners, or spurs to crime—sometimes all three at once. This is true to the pulpy genre Boyle works in, or at least to certain segments of that genre, and, to his credit, his configurations of violent men and untrustworthy women are rarely rote. For one thing, considerable interest is lavished on dames with disabilities. Along with two stories that center around sexualized victims of total paralysis, Death Don’t Have No Mercy features a memorable femme-fatale dental hygienist with an amputated arm. The mix of desire, admiration, compassion, and disgust for these damaged female bodies is one of the most uncomfortable and interesting aspects of Boyle’s book. Maybe it also expresses another idea about crime and crime fiction, this one more deeply submerged and conflicted than the others. Call it crime-as-obsession-with-the-vulnerable.

Then again, maybe this is just another expression of that first idea, that crime is not for the curious. Hard to imagine anyone more confounding of curiosity than a person who can’t move, speak, or even frown. In the end, the effect of these stories is something like locked-in syndrome, the crimes the characters commit as desperate as the blinking of men imprisoned in their own bodies.

Is that what crime fiction has to be, ought to be? Maybe, maybe not. Me, I think there’s still a case to be made for curiosity, unintelligible violence and hopeless paralysis be damned. I’d like to hear some more of that country-and-blues tape made by the kid from the Bronx. I’d like to see what Boyle would do inside the head of that one-armed dental hygienist.

Jamie May is a graduate of the Creative Writing Program at Florida International University. He’s at work on a mystery novel set in an early Soviet prison camp.