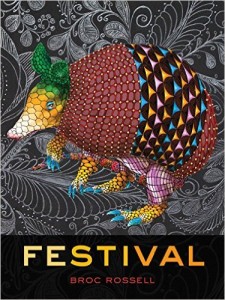

Festival, by Broc Rossell. Cleveland State University Poetry Center, 2105. $16, 98 pages.

It is common knowledge among poets that in Italian and Romansh, “stanza” translates to “room,” evoking the paradox of separation and connectedness, of transitioning within a discreet experience, such as a memory or reading experience. It is a relatively tired conceit, yet I can’t help but feel that the reading experience of Festival, Broc Rossell’s first full-length collection, is much like walking from one room into another, from space to unique space. Artwork by Aaron Cardella, ghostly ovular black-and-white images, like shrunken heads, or faces blurred by sonograms, appears throughout the book. Rossell productively works upon what Fredric Jameson called the failure of “cognitive mapping,” the inability of the mind to grasp the vast manifold of networks in which it’s inscribed. Indeed, while no sustained narrative develops, the poem makes sense locally, at the level of the stanza and across pages, inducing in readers the sense that the poem’s global sense is within reach. Reach, is in fact a central concern of Rossell’s: what can be kept from slipping beyond the reach of memory, what should be let go of as one moves from adolescence to adulthood, what declines into defamiliarization. Beauty and calm are found within those transitions and struggles. Festival is incantatory without attempting revelation, calling up aura and the actual, through a kind of lyrical dialectic.

This effect is augmented by the great number of seemingly memory-based moments across the book, its periods of conventional lyricism and its focus on setting and place. In one of the poem’s early episodes, Rossell writes, “In this version they shoot the white kid first. I am taken to a small but comfortable house on the verge of two landscapes, perhaps a forest and shore, where citizens wear a symbol of the void stitched to their chests…” Place grounds the poem, while events and reflections feel disembodied.

Rossell’s writing in Festival shifts form—there are page-long prose sections, and sparse, three-line, 12-syllable episodes:

The stars are closer

They move closer every year

Maybe this year there will be no snow.

The language is both analytical and narratological, chronicling declining suburbs and revivified self. Rupture and fracture are everywhere, and still the book-poem goes on.

Indeed, the tone of the writing is often conditional and ambiguous, which reads not as an effort at creating some kind of cheap ambiance invoking the strange or impending, but rather an attempt to speak to the fallibility of memory . Rossell addresses the ways in which the mind, even in the moment (precisely in the moment) of an actual experience, perceives and reacts. The piecing together of disjointed fragments is precisely how memory works:

Hope is a form of penance

like an oil rig

spouting as it bores,

I climb to discover the rock

Or the Virgin of Guadalupe visits

and labor assumes a purpose.

Romance purports a dialectic between loss and solace

but this clerestorial poem

has no house

admits no refuge

denies anything I can

remember

Though Festival is “I”-heavy, it is neither a solipsistic “I” nor the late modern/contemporary conventional poetic “I” that privileges catharsis. Instead, he uses a kind of anonymous “I” that is invested in a dynamic movement from particular to general experiences. Rossell, like George Oppen, John Ashbery, or Catherine Wagner, employs poetry not as a provider of “truth,” but rather as a tenderer of “truth.” Festival has no climactic, neat ending but instead raises open-ended questions, enacting one of the book’s main themes: the inadequacy of narrative to satisfactorily explain. Rossell’s poems create a feeling of “provisionality.” Resolution is postponed, and Festival plays with the inadequacies of narrative, even while implicitly arguing for the value of narrative through its numerous iterations. Rossell resists providing the reader with the kind of poem they are familiar with—conventionally transparent and linear. One can even read this choice as commentary on consumerism and its accompanying predictability: familiar package, familiar form and content, easily digestible. As the philosopher Theodor Adorno once noted, “When impulse can no longer find pre-established security in forms or content, productive artists are objectively compelled to experiment.”

While a distinctly meditative book of verse, Rossell’s reflections are investigative rather than pedantic, raising questions, not providing answers, though still remaining emotionally relevant and connected to the external world. He writes, “I want to kill a president, //just one” or in another episode:

It’s a ragpile

we bloomed out of in 1682

and in 1919 the quality of buttons

the thickness of stamped wool

and lynching still

about half a dozen

a month omega.

Festival offers the poem that plays hard to get. Here is writing that can be described as generative rather than directive, with Rossell and his reader participating in a collaboration from which ideas and meanings are allowed to develop. Rossell puts the poem in the readers’ hands; rather than explaining the poem to the reader, he rather “calls attention to,” thus creating a dynamic poem that resists didacticism. And so, Rossell’s poetry is like—in Adorno’s words—“Brecht’s plays, whose program actually was to set thought processes in motion, not to communicate maxims.”

Festival ends with a short excerpt from Simone de Beauvoir’s Ethics of Ambiguity, in which she explains the festival as the pinnacle of the transitory: where unhappiness is lost, happiness found, and joy evolves into new unhappiness. What follows is perhaps the most compelling section in the collection, which brings this concept to bear. It begins:

There are the water tanks. There is the skateboard in the ivy. There is the dirt lot with haphazard BMX jumps eroded into pebbled mounds and hollows, behind the row of shaggy, rotting eucalyptus.”

And ends:

My brother has been sent away. No one else is home. I take the boxes that are already in the driveway and put them in the car. I can feel the drugs wearing off. There is someone in the passenger seat wearing a shirt with my name across the back. I drive to the end of the block, put the transmission in park. There are cars speeding down the hill and more climbing it. I pass through them. Here I go.

In moments like these, which permeate Festival, Rossell reads, compellingly, like the illegitimate child of Will Oldham and Don DeLillo circa White Noise, evoking grim intelligence and bemusement, a particularly American numbness, and an underlying, quiet watchfulness and fascination. Skateboards and BMX bikes are keystones of ‘90s suburban American alternative adolescence, more redolent of Black Flag and Blue Velvet than Madonna and Top Gun, indicative of the desire to escape from the the usual authorities and experiment with controlled risks. But when the “festival” of adolescence becomes familiar it no longer offers all it once did, and when it falls into decline it creates a vacancy within that space and within those who have known it. With writing as complex and haunting as an empty amusement park, Festival does the traveling carnival complex justice.

Adam Day is the author of A Model of City in Civil War (Sarabande Books, 2015) and the recipient of a PSA Chapbook Fellowship for Badger, Apocrypha, and a PEN Emerging Writers Award. He directs The Baltic Writing Residency in Latvia, Scotland, and Bernheim Arboretum & Research Forest.