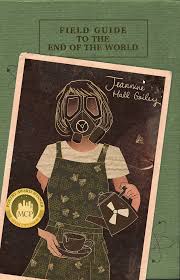

Field Guide to the End of the World, by Jeannine Hall Gailey. Moon City Press, 2016. 79 pages, $15.

In 2006, I stood in a clearing near Fort Richardson, Alaska, and watched as a Blackhawk lifted my husband and five other Airborne Rangers into the winter morning. They spun upward and hovered, low enough for me to see each man fall forward onto an air current, but too far away to know which one was Tom.

Iraq was already happening. Then Afghanistan. Changes in uniform patterns and ceremonial coins. A bronze star. There’s a picture on our wall of a man no one can find, sitting on a donkey, sweating.

Field guides riffle our bookshelves like mice. Guides written about knots and altitude and the limits of edible, guides for comforting the children of men who are shot at or trucked over bombs. I’ve read that embracing death is the most efficient way to avoid it, and the only way to ambush what’s following you is to walk in circles.

I know what I want from a book that promises survival: it’s got to be green. I want it to know more than I do, no matter how many times I finish it. It’s got to wear a gas mask, it needs to fit in a coat pocket. And it has to be poems. I want twenty-two of sixty-five titles to begin with “Introduction to–” so I know it’s all over, but not over.

Jeannine Hall Gailey’s most recent poetry collection, Field Guide to the End of the World, is a beast. It’s an event. Reading it is a reminder of the bodies we inhabit, their crushable clocks and colossal failures. Field Guide won the 2015 Moon City Press Poetry Award and was released in August in a volume that seems too slim for the magnitude of risk it controls. Perhaps what makes this book a must-read is that the speaker plays with humor and danger as only a dying person can.

The poems are post-WWI French surrealism meets American zombie movie meets hospice terminology meets the exact weight of a love letter. Nothing is certain. “Introduction to the Limits of Metaphor: A Love Poem” leans over the side of a bridge between realism and the unconscious daring of André Breton:

I have a wool sweater on my heart

you wear socks on your voice box

I am red lipstick you are the pair of shoes that goes with nothing in the closet

you are an untidy and scorched omelet I am a fallen soufflé

I am season one of Lost you are season nine of the X Files

I am missing organs I am the fallen starlet you are the boy born without a face

we are a pile of fur and feathers leather and oil stain

Civet cat and cigarette perfume wine glass and poorly knit rug (11)

While Breton fueled a literary movement on automatic writing and the reaches of the brain most connected to dreams in the early twentieth century, Gailey pulls that same strange thread into 2016 via post-apocalyptic postcards with Food Network, Martha Stewart, American Girl and HGTV. Pop culture drifts through the apocalypse on the same raft as a poet. Gailey warns us to “never write about dreams. There is nothing more boring than other people’s dreams” in “Introduction to Dream Interpretation.” But the poem is a suggestion in metaphor and vanity:

Find yourself a good oracle. If seven skinny cows eat seven fat cows, you might

want to watch out for the king’s wife. Angels or demons might be involved. If

the angel is spinning, it’s time to pay attention.

A good story needs no decoration, this much we know, but perhaps that rule applies particularly to apocalyptic writing, where poetic gymnastics do little to keep our skin on. We need poems that identify and instruct. We need poems that tell us how to survive the way a breath of subzero air trains us to sip slowly.

True to field guide form, Gailey ends the book with “A Story for After,” assuming there is an after. Even army manuals do this. At the end of a guide that has asked us to picture our deaths countless times, we will need to know how to find breakfast in the morning. Gailey leaves us beside a disappearing fire:

I draw a line in the dirt with a fork and draw a

picture – a house made of a square and triangle, a single daisy in the yard, and

two smiling stick figures. This is what we dreamed of, the day we awaited has

arrived. There are no more shotguns or dusty trails lined with diseased corpses.

…

All I need right now is you, the simple weight of your hand, the

warmth of your breath, and this last cup of coffee to tell me – we are miraculous.

Let me tell you, reader, this is all we need in a field guide, even as we fall from helicopters into one war after the next: brute strength, and the kind of optimism that feeds on reason.