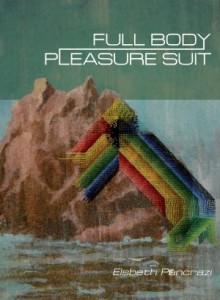

Full Body Pleasure Suit, by Elsbeth Pancrazi. Tavern Books, 2017. 76 pages, $17.

Elsbeth Pancrazi’s debut poetry collection Full Body Pleasure Suit consists of a series of linked poems in four sections, in which a first-person narrator leads readers through a place where virtual and object worlds collide. Through this liminal reality in which human interaction is mediated by screens, Pancrazi’s speaker guides us with confidence: we may not know the context of this space in which we find ourselves—its name, how it came to be, or its properties—but we can trust that the speaker knows. In this way, the book traffics in both utter mysteriousness and perfect clarity, like a long, visceral dream in which the dreamer understands the bizarreness that surrounds her even if it defies all earthly logic. The setting for these poems does not operate like a mere concept, therefore: through the power and certainty of Pancrazi’s language—with its insistence upon specificity, rich imagery, humor, and music—the reader experiences this world as if she were really there.

The four sections of Full Body Pleasure Suit present subtle variations in form and also serve to construct a romantic narrative of sorts. Starting from the very first poem, “When you fell asleep with your fingerprint on the sensor,” an “I” and a “you” are established: “I kept your hand warm. I kept my hand above the hand / on your controller….” The book continues to chronicle the two characters’ unfolding relationship, their attempt to navigate each other while navigating the alternate reality that houses them.

At first, I wondered whether the “I” and the “you” both referred to the speaker—denoting perhaps a self of the past and a self of the present (although the book’s sense of time is certainly not linear). In many ways, the series could be read as the speaker’s attempt to re-inhabit her own body, to utilize the same properties of this world that separated her from her body in the first place in order to find it again. The cover copy, meanwhile, states that the “I” and the “you” are indeed two separate characters. It’s a testament to the book’s strengths that both readings are possible.

There’s no question the four sections form an arc in which the speaker seeks intimacy with the beloved (perhaps herself) in a world that insists upon the opposite. It is precisely because of this opposition that physical intimacy comes to represent more holistic intimacy for the speaker, where the body becomes a site of resistance, a site of true union, within a virtual world. The contrasting forces of connection and isolation are apparent in numerous poems. In “We were standing together in a stand of everpink pines,” Pancrazi writes,

I was watching from above,

as from the canopy of trees you’d built

because I’d said we should unplug.

…

Watched myself begin to kiss you

on the mouth. But this was impossible—

In this poem, as with several others in the collection, the speaker is watching herself interacting with the beloved as if watching a movie. In this way, the implied distance is even more striking: not only is the onscreen moment of intimacy between the “I” and the “you” unsuccessful, the “I” is fractured across multiple spaces, thereby relegated to the position of passive observer as versions of herself attempt intimacy across these various divides.

Further in the book’s first section, in “Your dream has music, mine has,” Pancrazi’s speaker asks, “If you won enough tokens / for a global search what would you look for first? / I’d try to find one of our bodies.” In “At the voice transmission kiosk,” the first poem of the second section, she writes,

Listen, my throat

sooted with calls

rising like a chimney’s

indignant finger

to prod the sky

I wanted to tell you—

Each time, the speaker’s quest for intimacy is thwarted by the unpredictable, but seemingly predetermined, forces that surround her. At the end of second section, however, the speaker takes an “amnesia capsule,” declaring to the beloved that “On our honeymoon / I’m going to // forever first.” This transition into the third section, one long poem called “Body Swap,” suggests that the erasure of memory is crucial for union.

“Body Swap” unfolds as an ecstatic merging of the two characters’ bodies, and touches down in what appears to be a new setting:

I inhabit your softness and feel your softness

I inhabit your strength and control your strength

I inhabit your bruise and create your bruise

I inhabit the fullness and weight of your body in the hospital bed

being wheeled down the hall

As is true throughout the collection, the dynamic between the two characters is difficult to define—a mixture of love, loyalty, and varying distances, with the occasional suggestion of violence. Furthermore, the setting of the beginning of “Body Swap” begs the question: have we returned to the more recognizable world of the “past” (a literal hospital bed in a literal hospital), or are we embarking upon some kind of sci-fi medical procedure? The question, delightfully, proves unanswerable. “Body Swap” continues with the speaker, who is now merged with the “you,” being discharged from the hospital, eating at a diner, checking herself into a hotel (and masturbating in the shower), visiting a concert hall, going to work, and traveling to both the past and the future. The long poem ends with an incantation both creepy and sensual, with each reiteration commanding its own page: “I inhabit your body. // I inhabit your body. // I inhabit your body.” In the book’s final section, the characters appear separated once again—the union ruptured—but the reader senses that something has been learned, if not gained, from the experience of fusion.

What grounds Full Body Pleasure Suit, and therefore allows it to fly off in any direction it chooses, is Pancrazi’s skillful command of language. She offers the reader such striking phrases as, “pond sewn with many scattered swans,” “the long, rough tongues of grass,” “shards of bark,” and “cutlery racket.” The collection is saturated with these instances of rich imagery and diction. While the speaker attempts to pilot her own disembodied state, the reader is permitted the entirely embodied experience of Pancrazi’s textural and rhythmic lines. Moreover, she seamlessly weaves elements of our everyday life into the virtual life the book creates, in moments like, “Then dawn began to crossfade in,” or “a backlog of desire / updating my torso,” or “everpink pines.” It’s these subtle moments of integration that give the reader the unsettling sense that Pancrazi’s tech-ruled reality might be our own, after all—or else the one we’re careening toward. Regardless of whether her world is indeed our own or another world entirely, one thing remains certain when Pancrazi’s in charge: poetry plays a critical role in our navigation of the reality that surrounds us. No matter the obstacles, language is the medium that facilitates intimacy with others as well as with ourselves.

Cassie Pruyn is a New Orleans-based writer born and raised in Portland, Maine. She holds an MFA in poetry from the Bennington Writing Seminars and a BA from Bard College. Her poems and reviews have appeared in AGNI Online, The Normal School, 32 Poems, The Los Angeles Review, Poet Lore, The Adroit Journal and many others. She is the author of Bayou St. John: A Brief History (The History Press, 2017), and Lena, winner of the Walt McDonald First-Book Prize in Poetry (Texas Tech University Press, 2017). She teaches at Bard Early College in New Orleans.