Struggling against an “arctic blast” rare to New Orleans and its un-insulated homes, the mechanical thermostat in my house dithered just below 55 degrees, so I decided to seek refuge in NOR’s well-heated office. There, I fumbled through the very first issue of the magazine: Miller Williams’s New Orleans Review 1.1, published fall 1968 in a roomy 8.5×11 format.

In the days after Williams’s death on January 1 at the age of 84, it wasn’t just the cold that put me in the NOR office, but a curiosity about the person that started a magazine that has played such a central role in the writing and editing experiences of myself and so many others.

Miller Williams, a Loyola University professor between 1966 and 1970, came here under the agreement that he would be allowed to start a literary magazine, and, interestingly enough, most brief bios of Williams don’t mention Loyola University without acknowledging that he founded the NOR.

After his arrival in New Orleans, he quickly went to work establishing a network of support, relying on the many writers he knew and establishing new connections as well. By early 1968, he and NOR’s editor-at-large, Bill Corrington, had helped establish the New Orleans Consortium – a co-op consisting of Loyola, St. Mary’s, Dominican College, and Xavier University. The consortium pooled resources together to fund visiting writers. In his founding of the New Orleans Review, Williams had founded a community of support for writers and readers that fed the literary scene in New Orleans and beyond.

His student assistant between 1967 and 1968, a Loyola English major named Ralph Adamo, remembers Williams being a mentor of sorts, holding seminars on Beat poetry from a brown recliner at his house (on account of the spina bifida), and encouraging students to take part in the readings hosted by the consortium. “I’d give him twenty pages of poetry and he’d return it all marked up,” Ralph recollected. “They created a community for us, but also for themselves. It was kind of a scene.” Ralph’s first publication resulted from meeting the editor of Shenandoah at one of NOR’s reading events. Ralph, a poet himself, would return to NOR and serve as its editor between 1994 and 1999.

Williams used NOR to prop up established writers while also providing some validation through publication for emerging writers. When he founded the magazine, he wasn’t preoccupied with predictions about the magazine’s future esteem or possible lack thereof. But what he did predict in a way was the evolving importance of the emerging writers he decided to publish. Literary magazine editors do this, or at least should do this, with each issue published.

When a previously unpublished writer or emerging talent shares a binding with an established writer, say Joyce Carol Oates (issue 1.4, p. 326), an assertion is made and the mechanism of the literary world is offered new fuel. In its forty-seven years, New Orleans Review has been a launch pad for many new writers who have gone on to accomplish a lot of good things. Poet and novelist Rosellen Brown (issue 1.4, p. 362), who would publish her first of many books one year later, poet Alvin Aubert (issue 1.3, p. 275), who would publish his first of many poetry collections three years later and win a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, poet William Heyen (issue 1.2, p. 127 and 191), who would win NEA and Guggenheim fellowships and publish in The New Yorker, and John Matthias (issue 1.1, p. 52), who would soon publish his first of many poetry collections, are just some of the emerging talents Miller promoted in the early pages of NOR and in doing so helped affirm each writer’s potential.

A lot of these writers were in their twenties and thirties when Miller published them. It’s hard to gauge the impact that publication in Miller’s NOR had on the careers of these writers, but it’s clear that Miller saw something in their work that has been borne out in the years that followed.

And now, with Loyola students interning every semester, observing and taking part in the publication process, the magazine has more ways to support the evolving scene.

When did I start paying attention to NOR’s impact on my life? As a student intern back in 2003, I didn’t understand the magazine’s significance in my life and work, that I would soon use my internship experience to help edit the Washington Square Review, that I would someday return to NOR and be a fiction editor. It’s hard to predict how much it matters. Literary magazines replenish a well of creative material for readers and writers to experience, maybe not today, maybe in a different publication, but someday it all comes back to this magazine. NOR is where a lot of things begin. It is, after all, where I met my wife, which neither Williams nor I (anybody) could have ever predicted.

As the issues continue to roll out, hopefully for many years to come and with Miller’s vision and efforts in mind, a lot of the excitement will come from not being able to predict how much of an impact NOR will have. Even better, this is the kind of excitement that all literary magazines enjoy.

Peyton Burgess teaches creative writing and composition at Loyola. More about him here.

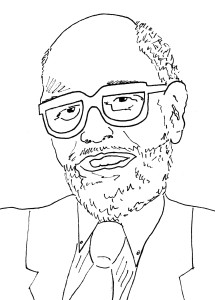

Illustration by Katherine Villeneuve

THERE WAS A MAN MADE NINETY MILLION DOLLARS

There was a man made ninety million dollars

had a vision of hell was afraid of the dark

knew that he had walked in evil ways

corrected his wife to death tortured his children

one to the priesthood and one to the crazy place

had done things besides so unspeakably dark

he could not honestly ask for God’s forgiveness

as he was only afraid and could never say

I’m sorry, Lord. He wanted such redemption

as wipes a life not clean but wipes it away

and knew that with all his money he could have it.

Spent his ninety million and ninety more

for fifteen years of the best brains to be had

in mathematics space-time and madness

and had him when he was eighty by God

a simple time machine which should not now

bend any imagination out of shape

went back seventy years to the same town

found himself at ten delivering Grit

stole the one car there was and ran himself down

left himself across a wooden sidewalk

who barely lied to his mother or masturbated

and went directly to heaven, if any can;

could never be the man who killed the boy

because he never lived to be the man

having died at ten delivering papers

survived by his parents, grieved by the fifth grade,

the first death by car in the whole county

killed by a runaway Ford with no driver

or if a driver, none to be found.

—Miller Williams (issue 5.2)