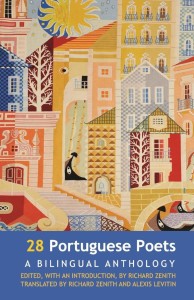

Margarida Vale de Gato is a Portuguese poet, translator, and Fulbright Scholar. Her first book of poetry, Mulher ao mar (Woman Overboard) was published in 2010, followed by Mulher ao mar retorna (Woman Overboard Returns), and Lançamento (either meaning to begin or launch, or to throw or cast) in 2010 and 2016 respectively. She earned her PhD in North American Literature and Culture with a dissertation on Edgar Allan Poe in modern Portuguese poetry, and teaches American Studies and Literary translation at the University of Lisbon. She has translated works by many 19th and 20th century authors, including Vladmir Nabokov, Oscar Wilde, Henri Michaux, Lewis Carroll, Alice Munro, and many others from English and French to Portuguese. Her poems are also in the recent anthology 28 Portuguese Poets (Dedalus Press, 2015).

INTERVIEWER

You translate and have written about many classic authors—particularly Edgar Allan Poe. Why Poe? Is he a special case that has influenced Portuguese literature to a greater degree than other canonical U.S. authors?

VALE DE GATO

When I had to choose a topic for a PhD dissertation, since I was working as a literary translator and had an MA in American Literature, I knew I wished to combine American and Translation Studies, and it did not require much research to understand that Poe was not only one of the mostly translated authors into Portuguese, but also one who had a very rich literary fortune. Mark Twain has nearly the same number of translated titles, but the difference is that he does not have such an high impact when you overlap the literary systems. Poe is unique in literary history since in his case—mostly due to the unrepeatable event of him having been translated by Baudelaire around 1856 and throughout the sixteen years of the French writer’s career—you really have to bring translation into the design of the development of literature and think outside boxes within strict national borders. So, Poe is very important for transatlantic modernity in literature, which of course includes Portuguese literature. I studied the influence in lyricism, where “nevermore” was taken as a catchword to signal the lament of the divorce of literature from action, and then there is a whole tradition of symbolist poetry caught by the “undercurrent of suggestion” sustained in the “Philosophy of Composition,” up to Fernando Pessoa, who would be very critical of Poe’s excessive emphasis on ratiocination, but at the same time draw from his mathematical mysticism. It is also noteworthy that Poe, who liked to absorb all that came from the other side of the Atlantic, was acquainted with a couple of Portuguese literary myths, including Inês de Castro (the prince’s lover who was killed by the king and later disinterred so that the court acknowledged her as queen), and some of the mysticism around the Portuguese word saudade; in fact, Poe adapted in The Southern Literary Messenger a reference to a Portuguese play by Almeida Garrett, and the phrasing he used in respect to saudade recalls the “mourning and never-ending remembrance” celebrated as a poetic achievement in “The Philosophy of Composition.”

INTERVIEWER

How do you separate or connect the identities of classic American or European writers from those of contemporary Portuguese readers?

VALE DE GATO

Let me narrow the question down to US writers, which are my scholarly field, and where “classic” can really mean 19th century, thus overlapping with “modernity.” For a time, I believed we were still living in “the long 19th century.” I am no longer sure where we are right now—with all kinds of terrorist and totalitarian regimes overthrowing the good legacy of the 19th century that was democracy and republican values (do not mistake values with party), and still with an unclear replacement for the awkward legacy of capitalism. But I’ve tried in my career and life to bring such writers to life, such as Emerson who’s spurred a tradition of environmental literature and ecocriticism, and Thoreau for giving us civil resistance, and Emily Dickinson in her subverting the government of masculine grammar.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned that though we are no longer in the “long 19th century,” you can’t define where we as a society are in now. Do you see detectable changes in literature as we move away from 19th century values? And do you think there is a way to approach contemporary writing (or even art) in a similar way as you approach much of the 19th century literature you have translated?

VALE DE GATO

Well, maybe I am so fond of studying the 19th century and early 20th century because that’s the start of things that still affect us—complex geopolitics, textual commerce, circulation of insubstantial capitals, blurring of fact and fiction overlapping in the same media, etc.—and yet it has quite reached the World Wars and the subsequent threat of mass destruction. What comes after that maybe is not so much post-modernism but post-apocalypticism. As for contemporary literature, I read a lot of it and teach some. The mixture of the casual and the complex is what is more baffling about it—and more exciting, as in society. How do we reconcile these things: the fact that we are more and more haunted by what’s shattered while at the same time building more and more complex systems of fluidity and speed?

INTERVIEWER

Much of your own poetry is focused on the act of poetry itself. Is this an intersection of your academic and creative work?

VALE DE GATO

One line of a late sonnet of mine reads “I’d like to make love and poetry at once / & by any cost subvert Italian verse.” Poetry, love, sex—and God, and activism—are things that to me have always been linked with the same quality of excitement, the excitement at the brink of a revolution. I like to write about what thrills me and poetry is obviously one of those things. The fact that I teach poetry and that I have a hands-on approach to diverse traditions of poetry through translation makes it exciting to unmake poetry, too, and I guess I write about it. What I mean is that it’s not so much the academic part that interests me, the meta-poetry, but the focus on poetry as one of the amazing facts–and struggles–of life.

INTERVIEWER

How do the works you’ve translated inform your own writing and poetry?

VALE DE GATO

Translating poetry has certainly improved my ear and widened my lexical choice. Sometimes it is hard, though, to write while translating because you are immersed in the other poet’s voice. Sometimes you allow for immersion to overflow your “poetic sentiment,” and this somehow gives you a greater margin to play with in rewriting, because you partake of the authority of whom you are stealing from. Also, my job as a literary translator has allowed me wonderful literary discoveries and long-life relationships, like Michaux and Sharon Olds, to cite just two writers I might not have deepened my acquaintance with if it were not for translation.

INTERVIEWER

In response to translation and your own poetry, you mentioned that translation often forces you to immerse yourself in the artists whom you are translating. What does it mean for you to “steal” from an author you are translating?

VALE DE GATO

Fair game. Unfortunately, if you do it too much, you might get caught.

INTERVIEWER

When you translate pieces, do you focus more on the diction of a piece, or the feeling the piece gives you? Do you think there is a middle ground between literal and “artful” translation?

VALE DE GATO

Yes, artists like to be radical. But translation is important for my balance, and I hope my translations do take the reader midway to another’s diction. To answer the first part of this question—poetry is made with words, so there is actually no opposition between feeling and diction.

INTERVIEWER

I have only ever written in English and am interested in learning about your process of writing and translation as a poet. How do you approach translating your own works? Are things added and lost in the process of translating an original piece, despite the fact that you wrote it?

VALE DE GATO

I very much like George Steiner’s concept of “restitution,” which according to him is the ultimate (and rare) stage of translation—when it makes us read for the first time what was already there. So when a poet self-translates s/he is making new discoveries about what was found in the poem in the first place. Translation reminds us of the transient nature of speech, however much poets would like to believe in the staying powers of words. Poetry, on the other hand, is also sustained by the faith in the chance encounter. And translation, despite all, is one of the activities that requires more purposeful choices. I enjoy the dynamics.

Anahi Molina is a student and writer based in New Orleans. Her writing has been published in The Millions and Big Muddy. Follow her @anahianabye.