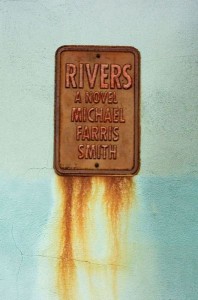

Born in rural Mississippi, the son of a Baptist preacher, Michael Farris Smith has been heralded as a new voice in Southern fiction. Smith’s numerous literary voices, though, are as autonomous from Southern fiction as they are from American fiction. Since his debut Paris novella, The Hands of Strangers (Main Street Rag, 2011), Smith has sought to loosen the bonds of sublunary literature by creating worlds that palpably realize our worst fears—no matter how irrational those fears may be. Smith’s first novel, Rivers (Simon & Schuster, 2013), is being hailed as a post-apocalyptic, post-Katrina work that defies genre boundaries.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s discuss Rivers, which is scheduled for release in September 2013. One of the most striking features of this novel, to me, is the government’s decision to abandon the region below the Line, which is roughly drawn south of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Later on in the novel, we learn that the decision to abandon those people spreads to the rest of the South. Do you think the South takes lower priority in U.S. politics?

SMITH

I am ashamed of the government’s lethargic response to Katrina. It was a lethargy that seemed to continue along the Mississippi gulf coast for a couple of years, where the novel is set and close to where I was born. I think it was a crying shame that the very first thing that popped back up on the gulf coast were the casinos, while ordinary people lived in trailers for years.

INTERVIEWER

Some awful things happen in FEMA trailers in Rivers. In a recent interview, you talked about once writing several drafts of a post-Katrina novel and throwing them away. Then, you landed on the story for Rivers. Why did you choose this hypothetical situation rather than an actual depiction of events post-Katrina?

SMITH

The last thing I wanted to do was to write a contrived Katrina novel. With my hypothetical hurricane-ravaged region, I was free to do what I wanted without feeling a guilt that I wouldn’t do justice to the actual people Katrina involved. Because these were hypothetical people in a hypothetical scenario versus real people in a real scenario, I could let it fly.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think this novel still makes a significant statement about real humanity in the face of disaster?

SMITH

I didn’t really set out with the intent to make a statement about anything, but I do think the story illustrates desperation and how far people are willing to go, not just to save themselves, but to save others. When you think about desperate times, a lot of times we think about the bad: the lengths people will go to protect themselves. But in reality, people also go to great lengths to save others and put themselves secondary. I always want to write about the human spirit, and there is nothing better to test your characters’ spirit than desperation. I always want to be putting characters in deep, dark places and see what they are made of. Just like in real life, some people stay in those deep, dark places and do terrible things, but some people scratch and claw their way out of those places, and find themselves capable of things they didn’t know they were capable of doing. And it’s not always about what we are capable of physically, but emotionally. In Rivers, Cohen eventually did some things he didn’t know he was capable of at the beginning of the novel, both for himself and for others. At the same time, the dark characters in the novel are doing things they never thought they would do. Joe, for instance, went in a strange direction and thinks, “How did I end up being this type of man?”

INTERVIEWER

You said once that what interested you in Rivers was that the destructive force was completely out of human hands. How do you think that changes the complexion of the novel?

SMITH

I think the characters are more helpless because the destructive force is the weather. It’s not an atomic bomb. Who do you blame? If it’s a manmade force, you at least have elements of good and evil who can fight with each other and try to stop whatever is being forced on mankind. There is no good and bad fight when Mother Nature is your enemy. There’s no one who can do anything about it. All the characters have to realize that. I think it adds to the helplessness of the scenarios. I felt helpless as a writer. I thought, I’m about to hit them with another one. What can they do about it? Nothing.

INTERVIEWER

How did you go into constructing an imagined landscape that feels so real?

SMITH

I didn’t put that much focus on the imagined landscape of Rivers being this otherworldly place because all fiction is otherworldly. My Paris in the Hands of Strangers is another world. It’s not Hemingway’s Paris. That’s the way I see Paris and interpret it. Faulkner created an entire community with its own geography and family lines. Is Yoknapatawpha County any more experimental than Ray Bradbury writing the Martian Chronicles about astronauts, planets, and rockets? Neither one of these worlds exist really, except somewhere in the minds of these artists.

It probably helped me that I made the setting of Rivers so defeated because it is an abandoned land; therefore, I could just pummel it. You know, if it would have been halfway populated and halfway struggling, then it likely would have been a bigger chore. But because it was a big wet wasteland, I could really revel in those images of nature: what a storm looked like, what lightning looked like, or how the thunder sounded. Azaleas and honeysuckles had grown wild and free, and I focused on how the animals roamed. Surprisingly, the landscape felt strange to me once the characters started making their way north to a place with electricity.

INTERVIEWER

The situation of the novel is interesting, but the characters determine the worth of the story, ultimately. Why did you choose Cohen as the main character of Rivers?

SMITH

All I had to begin with was an image in my head of this man named Cohen waking up in the middle of the night in the middle of a hurricane. When the rain slacked off, he went outside to look around. I didn’t know who he was on the first page; I didn’t know what he had to do, but I did feel he had an odyssey in front of him. I didn’t know what the journey would encompass: love, life, death? He becomes heroic to me for some of the reasons we’ve talked about, but he’s also anti-heroic to me in some ways because he makes some difficult choices when he is forced to act in ways he didn’t know he was capable.

INTERVIEWER

The present is so awful for the characters in Rivers, yet most of them are troubled by their past. In fact, many of them live in the past.

SMITH

Those who decide to stay beneath the Line beg the question, Why the hell are they staying down there? I had to answer that question for every character; it wasn’t enough just to place a character in that setting. I liked that I had to do that because it taught me a lot as a writer. A lot of the revision process was going back in and really developing these characters.

INTERVIEWER

Another aspect of this novel that really struck me is the Venice narrative that emerges from Cohen’s memory and runs concurrently from chapter to chapter alongside the apocalyptic narrative. Where did this idea come from?

SMITH

I wrote a five-page flashback scene just to give some background on Elisa and Cohen. They go to Venice, she likes it there, he makes a couple of cracks about being surrounded by water, and that was it. I was initially doing it for the irony. Then, my agent said to me, “Why don’t you write about that trip some more.” So I created a separate document and wrote about twenty pages of their experience in Venice. It involves some foreshadowing, and I spliced it up throughout the narrative. It’s sunny in Venice, so it gives you some light and warmth in the middle of all of this darkness. You learn about their relationship.. It happened by accident, but I was happy with the way it turned out.

INTERVIEWER

The second narrative literally makes the novel literary because Death in Venice pops up in conversation.

SMITH

Death in Venice is one of my favorite books, and it was satisfying to me to be able to work that book into the storyline of Rivers. That book is about man against himself, his spirit, and his subconscious. It is somewhat ghostlike. The main character is delusional at times. The big question that hangs out there is what is right and what is wrong and who’s to say? I think Death in Venice and a lot of Mann’s work are fine examples of man’s greatest enemy sometimes being his own self.

INTERVIEWER

Why do you think Rivers is hailed as a Biblical and a morality tale?

SMITH

I think the religious overtones are fairly obvious. That was a natural thing to incorporate into the novel. I’ve read a lot of Cormac McCarthy and Faulkner. Many of the stories I’m drawn to involve a battle of spirit. Think about The Old Man and the Sea. It’s a battle of man and his spirit.

Cohen is a man pushed to the edge, and in his isolation and in his desperation, he’s grasping and surprising things are coming out of him. At one point, Cohen writes a note, “He is not dead; He is risen.” I thought, Why did you write that? But the line seemed perfect. He’s grown up in South Mississippi, so he’s been in church and he knows a handful of hymns he can probably sing by heart. He’s been taught right and wrong. I think when you’re hanging at the end of a burning rope, you’re going to question God, maybe assign blame to God, or at least wonder what’s going on, and why is it happening, and oh, by the way, can You help me when I need it?

INTERVIEWER

There are spirits throughout this story. What drew you to that angle of the story?

SMITH

I’ve heard people refer to this story recently as spooky. That never crossed my mind when I was writing it. It makes perfect sense in retrospect, though. You know, the supernatural world is so interesting because nobody knows exactly what it involves; there is so much unknown. This is one reason the Southern Gothic is so fascinating to me. When I read Other Voices, Other Rooms by Truman Capote, I thought, What an awesome Southern Gothic novel! There are ghosts and spirits everywhere. The human imagination can take those things, amp them up, and make them so real. When you are stuck, the supernatural comes to life because you see things that you don’t really see, or hear voices that you don’t really hear. Perhaps my characters seek and find these spirits because they are so isolated, and they are all looking for anything to hold on to in order to maintain sanity.

INTERVIEWER

After you wrote Rivers, did you take a trip to the desert?

SMITH

No, but I tell you what: I was ready to go for a walk in the sunshine. It rained for about six weeks straight when I really started working on this novel back in January of 2010, one of the rainiest winters we have ever had. I sat in my study next to a big window and watched it rain almost every day. It was like God touched me on the head and said, “Here you go, buddy. I’m going to help you out. Here is your push.” Really, I sat there and watched and listened to it pour down rain as I wrote the first one hundred pages of this novel. Everybody around Columbus was bitching about the rain, and I said, “Let it rain.”

It was pouring down rain the day our family got the news about the acceptance of Rivers. I got in the car with my wife to celebrate, and I was soaking wet. I guess the rain and I will always be attached.

James Madison Redd (PhD, University of Nebraska) is Prairie Schooner’s blog editor and the founder of the Crooked Letter Interview Series, which features contemporary Mississippi writers, including Richard Ford, Chris Offutt, and Natasha Trethewey. These and other literary conversations have appeared or are forthcoming in Prairie Schooner and Oxford American.