The whole thing—to do it and to bring her here, home where the back room is empty, clean, with burglar bars covering windows on banana plants in the alley, all that: Jon’s idea. We’ve laid in a supply of Depends and vegetables. We’ve read. We’ve prepared, figured it all out. We have the TV on a rolling cart, and we can hear her excitement when she feels the wheels coming down the hall, thundering against the hardwood floors, humming along the runner. We can do this, Jon assures me. This will work.

We see her on the news, but we don’t see us. That’s good. That means everything is still go. When she sees herself, she smiles slyly. Jon says, She knows who she is, she knows what’s going on. She knows, he says. We saved her and she knows. She’s not stupid.

*

The Depends are easily changed, and though they’re new for her she doesn’t make much of a fuss. This was one of our fears, the mess she would make, the noises the neighbors might hear. But she’s quiet. Maybe, Jon says, she understands, maybe she’s in tune with what’s going on, that we have a noble purpose, that we’re the good guys. She’s not stupid. Maybe Jon’s right.

*

Should we have contacted an agency beforehand? Yes, perhaps, but wouldn’t they simply have talked us out of this? We don’t see the use in picketing, in writing letters. We don’t see the use in waiting for something to happen because Turvy decrees that it should, that he agrees. As it is, Turvy holds too much power and that’s what brought us to this “extreme.” Extreme is the newspaper’s word, not Jon’s. Is the necessary ever extreme? Isn’t it simply necessary? Jon thinks so. Famous philosophers agree with him. Jon has read them.

*

Jon attends morning classes in zoology, ethics and drama. He has told me not to go in with her while he’s gone, in case something should go wrong. Not that anything would, really. I can’t stop going to classes, Jon says. We must not let anyone see us acting any differently. We must buy only one or two boxes of Depends at several K&B’s. We must not draw attention to ourselves. We must not go overboard, Jon tells me. Everything is normal, he says.

Everything is normal. It is.

*

The breakout was easy. The cheap fence melted waxily between the jaws of the wirecutter, and the bolt was just a standard Masterlock Jon opened with a key ordered from an anarchists’ catalog. We’re here, I said, peering into the shadows behind the door. We’re here, I said, as though this was some appointment we’d made, as though she would be expecting us. In the darkness, I could see her shape, but not her eyes. We’re here.

*

After Jon leaves for classes, I read in my room, watch TV, think about her just sitting there waiting to discover what will happen next. After Love Boat I creep down the hall and put my ear near the lock to hear what she’s doing—crying, pacing, snoring. And I can feel her through the door immediately, feel her heat, her hot and sour breath squeezing through the cracks around the hinges, touching my face. Hello, I say. It’s OK, all right? Everything is fine. You’re fine. She sighs, I sigh back. Everything is normal, I tell her. It is, I say. It is.

*

Postmark—Venice Beach

Dearest: Got your letter. Life there sounds bizarre, but isn’t that what one would expect? When are you finally coming out here to visit? Our weather’s better. We fluctuate rarely. Enclosed is a very smallish check. Do not thank me, just spend it. Have fun. Isn’t it almost Mardi Gras? Send good beads. Big white pearls go with everything, right? All my love, always. D.

Jon says we should wait a bit longer. Public outcry is subsiding, turning around. We aren’t the bad guys anymore. We’ve done something a great many people wish they had the balls to do, Jon says. This is his interpretation of the newspapers he does not bring home, that he reads in the coffee shop between classes. On the news, we see a report that seems to back up Jon’s surmise. Just a bit longer, Jon says. Just hang on. We’re winning.

*

She’s strong but gentle. I’m surprised by how thick her muscles feel when I pick her up to change her Depends. She is not embarrassed about the mess. She does not look away from me or Jon when we are with her—unless the TV is on; then she watches that, no matter what’s showing. When Turvy started running commercials asking for her return, offering rewards, I watched Taffy’s face to see if it registered who he was. She did not howl in rage as I expected she might. She put a hand to her mouth and tugged lightly at her lip. When Jon and I rolled the TV out of the room that night, she moved on her pallet as though she wanted a hug, and I went back to give her one. The hair on her arms tickled the back of my neck. Good night, Jon said to her, indicating that I should stop, come to bed.

Good night, I told Taffy, prying away her grip.

*

We should be able to get any number of groups involved, Jon says. Any number of groups will want to be a part of this. He looks at me. The TV’s glow colors his chest like a Blue Meany from The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, naked, vulnerable, hairless. Do you think she should go back to Africa, where it’s hot? he asks me.

It’s hot here, it’s hot here almost all the time. We’re in Africa, Jon, I say. Excepting a few freakishly cold days, Baton Rouge is Africa, I tell him.

OK, OK, he says. OK. Don’t go ape on me—ha-ha?

Not funny, I say. Not ha-ha. It’s January.

*

I give Taffy some sugar cubes, though Jon has forbidden that. She’s had enough crap, he said. Caramel corn, cotton candy, sno-cone goop. Fuckers poisoned her, he said. This is true, I know. Her Turvyland diet was unnatural, unhealthy, poorly planned. But still, I give her two cubes one day and watch her eyes, and they do light up, they do, there is recognition there, and by the way she looks at me I know she is grateful, thankful for the poison I am kind enough to provide.

*

I roll the TV in the next morning after Jon leaves. I take a big throw pillow in and sit on it. Taffy crouches on her pallet. It’s chilly, close to Valentine’s Day, and so I turn the heater on high and we watch Rosie O’Donnell talk to Dolly Parton while the air gets more and more African. I can smell her. Not the Depends—she’s clean—but her skin and her breath. By lunch it must be over ninety in the room and I am beginning to smell myself as well. I take a bagel out of my pocket and break it in two. Taffy eats it slowly, contemplatively. She motions as though she would like a drink of my Snapple and I give her some. We watch Star Trek: The Next Generation. We wait for the sounds of Jon coming home. We pant at Captain Picard.

*

Postmark—Venice Beach

Darling Brubba: You kill me. I swear, half the scripts—no, more than that, seven-eighths—don’t have a smidge of the imagination your letters do. Come, let me represent you. Don’t worry about the past; we have lawyers here who do that for you. Besides history just means story, right? You’re colorful. Add style (Barney’s has a killer sale on) and you’re nothing short of fabulous. A check is enclosed. Nobody in the office can believe how cheap life is there. Come testify in person. Love you. D.

*

I called from pay phones, he tells me. It’s too sensitive for them to handle. She’s ours for a while, though one group says they may be able to get her into San Diego, smuggle her in. We smuggled her out; we smuggle her in.

We need more Depends, I say.

I say, Gather, Jon, gather.

*

Neighborhood cats perch on window sills, staring in. Taffy and I watch them. They do not excite her, I can tell. She’s seen better, I imagine, bigger ones, more dangerous, in a jungle. The cats look in, and we look back. An occasional dog bark scatters them, forcing us back to the TV. We are beginning to catch up with Guiding Light. We recognize characters, dilemmas, sets. We become involved, get hooked. The drama’s rhythms become our own.

*

One day I put on a Depend myself, just to see what it feels like. Taffy observes. She looks at the manhood between my legs without interest, watches it disappear in the plastic whiteness of the diaper. I sit on her pallet, and she moves closer to the TV. She has great interest in Bob Barker. I have not bathed and when I pull my shirt up over my head, my odor sneaks around and up to my nose and I like it. I watch Taffy watch Bob and I force myself to shit and sit in it. I pee and am amazed by its warmth against my body. Taffy used to watch people watch her between their rides on the merry-go-round and bumper cars, now she watches TV. During a commercial for car insurance she turns to look at me. She knows I have shit myself, pissed myself. She knows, but she doesn’t care. She massages her left ear. She is ready for the Showcase Showdown.

*

Baby, Jon says, get cleaned up. He says, What happened here?

I fell asleep, I tell him, as though that will explain the diaper, the mess, me and the TV and Taffy in a sea of Milky Way wrappers. I fell asleep, I say.

*

The next morning Jon does not go to class. I want you to get out, he says. Go to the store, the library, the park. Get out for awhile. I’ll be here, everything’s fine. You take some time for yourself. Get out and live. He pats my shoulder and kisses my cheek.

*

I go to Turvyland. It is closed, but the gate swings open at my touch. On my way to Taffy’s cage I pass the spot where Jon and I broke in—or where I think we broke in. The fence has been mended. I halfway expect to see yellow POLICE SCENE tape around the cage, but there is none. And nobody is around; I have returned to the scene of the crime, but no one’s here to arrest me. I look at the lock on the cage door, anticipating fingerprint dust, but no. Hello, I say, hoping somebody will materialize so I can explain my concern for Taffy’s safety, register my alibi, my excuse for coming to a winterized, small-town amusement park to see an empty cage. Hello, I say again, but nobody appears, so I climb in and look through the bars at the boarded up ticket booths and dismantled Scrambler. It is sunny and cold in Turvyland, empty and unguarded. Turvy is not here, clearly, not around for me to lie to, bite, or kill. Behind the Tilt-O-Whirl are the Bumpercars, behind them the House of Mirrors, behind that I can’t see.

*

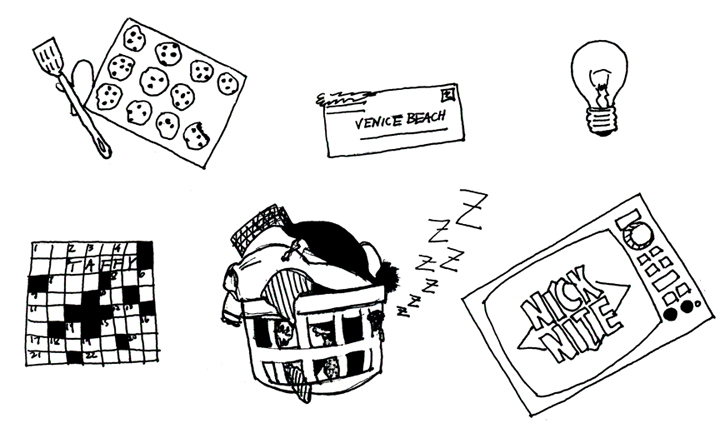

What did I do before Taffy? I read. I did crosswords. I wrote my sister letters and waited for her to write back. She is a very generous woman. Late afternoons, Jon taught me what he’d heard in lectures that day. Like two degrees for the price of one, he’d say. I listened to National Public Radio. I clipped coupons. I napped. I watched Nick at Nite. I switched back and forth between AT&T and MCI, pitting one against the other, negotiating deals for free minutes, free money. I did yoga. I baked cookies. I called my first boy friend’s mother in Hawaii for tales of what her terriers had done that day. I watched Biography. I did laundry. I folded sheets. I put away dishes. I changed lightbulbs. I read ahead on The Far Side calendar. I wiped the baseboards. I chose 11 CDs from Columbia House, then threw away the card on which I’d marked them.

I did lots of things.

Those are just a few of them.

*

We have a problem, Jon tells me. She killed a cat. I was in the kitchen making hummus, and I guess she broke the window and reached through the bars to grab it. The cat is on a towel outside Taffy’s door. It looks like a stuffed animal with its head sewn on backwards.

Taffy, I say, and I can feel her leaning against the door, breathing through the keyhole, feel her waiting for me. Get the TV, I tell Jon. Be a good boy and get the TV.

*

Postmark—Venice Beach

Sweetheart: Went to a party at a certain “Captain’s” house in the hills. Told him my crazy brother was a huge fan. “How huge is he?” he asked. Ha! Loved your last letter. This monkey thing is great. “Planet of the Apes” meets “Free Willy” with some “Altered States” thrown in. We could pitch this one as a team, darling. The dynamite duo, together again. Brubba, come where you belong—Hollywood, U.S.A. Do you like sushi? Big kiss. D.

*

Turvy’s on the news once more, offering an enormous award for Taffy’s return. He is crying. He promises to build her a new cage, one that isn’t a cage at all but a natural habitat enclosure. He misses her, he says. He shows an artist’s renditions of what Taffy’s new home will be like. He stresses the words waterfall, bamboo, and boulders. He begs forgiveness. He says he knows we’re good people, we’re in the right, we are not thieves, not terrorists but teachers; we’ve taught him a valuable lesson, he says. Support for us has been overwhelming. The public demands he do the right thing, and he wants to. He will give Taffy a home, he says, a real home, some place comfortable, beautiful. He does not mention a TV, which disappoints Taffy, I can tell by watching her face. There is no Magnavox in the artist’s rendition. Bring her back, Turvy begs. There will be no questions asked. Give me another chance. I’m on my knees here.

It looks nice, Jon says. The faux natural habitat. It looks like the San Diego Zoo. Well-designed. Comfy, even. He’s been on pay phones again, asking about help, alternatives, striking out with even the most radical activists. I wouldn’t mind living in a cage like that, Jon says. I think that would be sort of swell. I think we’ve given Turvy a heart, don’t you? We’ve de-Grinched the old so-and-so.

We’re running out of Depends, I say. We’re not just low. We need more now. Now. She’s dirty, I say. Jon has not repaired the window Taffy broke. A whiff of fumes from the riverside chemical plant drifts in, sulfuric, and my head begins to ache. Go get Depends, I tell Jon. Go now, before they close, I say, though they never close; drugstores around here never, ever close.

I’m going, Jon says. He jingles the car keys in front of him. Depends and anything else? Juice Bananas?

It’s a nice night, I say. Why don’t you walk?

*

Taffy seems to expect the seatbelt. She does not fight it, which strikes me as a good omen. She does not balk at our high speed reverse out of the driveway. She is calm, reaching gingerly for the knobs of the stereo, recognizing it is the closest thing to a TV we have for the moment. She is not upset by our velocity, the screeching curves and run stop signs. She has spent a great many years watching the Scrambler and the Tilt-O-Whirl, the Bumpercars and Carousel. She is not afraid of motion; she is ready for it. We’re both ready for it. She’s got a ticket to ride, the Beatles sing on the stereo, and Taffy stops turning the dial at last, satisfied. She’s not stupid. She knows what’s going on. She can smell Hollywood ahead, on the wind, in our future. She’s not stupid and everything is normal.

It is. It is.

Matt Clark’s novel Hook Man Speaks (Putnam/Berkley, 2001) was chosen as the inaugural title for the Texas Monthly Author Series. When he died in 1998, at age thirty-one, Matt was coordinator of the Louisiana State University Creative Writing Program. His stories have appeared in One Story, Southwest Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, Gulf Coast, Flyway, and Yalobusha Review, as well as in the anthology Texas Bound. While a graduate student at LSU, Matt was fiction editor of New Delta Review, which now sponsors the Matt Clark Prize in his honor. This story, “Taffy of Turvyland,” is from Matt’s unpublished collection South/West.

Illustration by Katherine Villeneuve