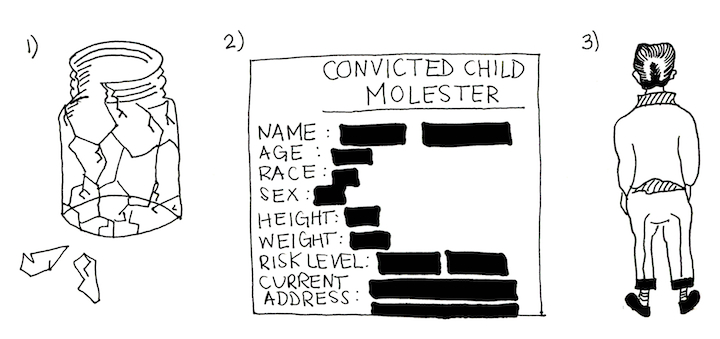

In the afternoon three things happened to bother me. In order:

1) I read a Times article about the last eunuch of the Chinese emperors dying alone in a Beijing temple. Most eunuchs had saved their “three precious” in jars so that they might be buried with them, ensuring a full reincarnation. This last eunuch however did not have that luxury; his family long ago destroyed the jar lest a new regime punish them for holding on to the old ways.

2) The mail came, and among the pizza coupons and magazines lurked a flyer announcing a convicted child molester had moved into our neighborhood. The card was from the child molester, actually, legally required to inform each household within a certain radius of his new residence, his bogeyman presence. My name in his handwriting looked foreign, unpronounceable.

3) I spotted the Squid in the coffee shop near our house, unseen since the beginning of cold weather in Baton Rouge, when girls from the nearby Catholic school began at last to keep their uniforms securely in place, stopped taking off shirts to reveal sports bras, ceased sitting in the brick courtyard smoking Native Spirit cigarettes and sunning themselves, applying lotion from a communal tube. Once it got too cold to tan, the girls found somewhere else to hang after school, some warm den echoing with the voice of Oprah—and the Squid went away to hibernate, to savor his remembered images of those girls in their plaid skirts, pierced belly buttons just above tartan wool. But today, he was back—ducktailed haircut, highwater pants and all—smiling at the new girl behind the counter, asking if this was her first job, how old she was, what was her name.

I know—it’s a bit much, connecting these three “events,” allowing them to build to something in my mind, accumulate meaning, to let myself be bothered by them. But still, imagine that triple-play wandering into your life one short, bitterly cold afternoon just before Christmas; see if it doesn’t upset you. See if you don’t look for an underlying message.

When I tell Randall, he doesn’t want to talk about it. “Christ,” he says. “You have got to find something better to do with your life between semesters than dream up conspiracies of fate. If it had been just one thing, would you be this freaked?”

“Yes,” I say. “Though not so much, maybe.”

“OK, the child molester business,” Randall sighs. He puts down the new Harper’s and turns toward me. The TV is on, of course—the only way Randall can read—and my eyes keep being pulled away to the action occurring on-screen. “So, there’s a child molester in the neighborhood. Do we have any children? No. Will we ever? Doubtful. Two men adopting a child in this state would go over a little less spectacularly than a child molester moving in next door. And please do not get started on the stats; I know pedophiles are always straight, white men. I know all that, so don’t even go there.”

“I won’t,” I say. I’m watching commercials, fearful of what may appear, expectant. The holidays are over, but on TV people are still arriving at upper-middle class homes bearing elaborately wrapped coffee makers and VCRs, McDonald’s gift certificates. Any one of them, any one of the actors could be a pedophile, a eunuch, an up-and-coming celebrity. Any one of these people could be in the papers tomorrow, featured, grilled, seared by flashbulbs.

“And the Squid thing,” Randall continues. “He’s a pervert, OK, a Humbert Humbert without the vocabulary. But I doubt he’d ever try anything beyond staring, accidentally brushing against them at the sugar counter, so no worry there. Really. Plus, they’re not our daughters, for reasons we’ve already covered, so your concern, though admirable, is a little over-the-top.”

“I don’t think so.” I turn away from a sitcom I’ve never seen before, something set in a deluxe radio station. The lead actor looks exactly like Randall’s ex. He’s handsome, too much so, unnervingly good looking, with skin like an Italian ski-pro, both dark and rosy. I can tell he looks great on a beach, and I hate him.

“OK,” Randall says. “So. Whatever. As for the eunuch business, I don’t get that at all. Hello, he was a eunuch—didn’t have a sex life. Not a child molester. Not a monster. Just a sad man who died without much solace even in that death. If you’d read an article about some civil war general being buried without his arm, would you be upset like this? It’s basically the same thing.”

It’s not, of course, but I know too well that arguments like this never resolve anything and Randall always is made happy by my simply giving up, something his law partners refuse to do, a victory he never sees between the hours of eight and five. “I’m beginning to see your point,” I tell him, trying to hold my gaze to his own, though I can feel the TV pulling my eyes away, wanting my attention, demanding it. Something is going to happen; there is a sign forthcoming. I will have my fourth fragment, the one that will connect the dots, thereby defusing my discomfort. Like the eunuchs, I have my superstitions, too. Four is coming up. I can feel it, the pricking of its approach on the back of my neck.

“You feel better?” Randall asks. He wants to help, he really does. This is as much a part of his victory as the knowledge that he is right, that his rightness is in some way healing, that his rational thinking brings closure.

I swallow the truth. “A little.”

Patting my knee, he repositions himself, pulls the Harper’s back into his easy view, smooths the page he’s on.

The sitcom ends, replaced by a commercial for the new Jacques Cousteau special, surprising since I thought Cousteau died last year. In slow motion a diver floats yards from a great white shark. He is not panicked, hasn’t even raised the speargun he holds. Clearly this is number four. It’s a shark, true, not a squid, but clearly this is number four. Clearly I am to kill the Squid. Or no, not kill it—simply guard against it. The diver isn’t attacking. He is watching, observing, keeping an eye on the shark. Don’t kill the Squid, but be aware of the Squid. Better yet, tell on it, report it, write a letter to the school, alert the nuns to warn their charges.

The connections don’t add up, obviously; I realize that. They only lead somewhere, a trail. The eunuch has no place in this that I can see, excepting how he got me electrified, how he started my move toward this realization and decision. Stop the Squid, I say to myself, underlining the words, making of it a mantra, a slogan. Spring is not that far away, the sun is heating up and the girls are soon to be smoking and tanning in the coffee shop courtyard. There is time, time to think, to compose the necessary communique and fend off the Squid’s April debut. Dear Sisters, I think. Dear Nuns. Dear Mother Superior.

“We’ll never have children,” Randall says, fingering the remote absentmindedly, switching to the Weather Channel and its lists of temperatures, all cold. Baltimore, Barstow, Boston. Cheyenne, Chicaqo. Detroit.

“Well, no,” I say aloud, answering Randall, but inside I’m not so sure. I don’t like ruling out possibilities, good or bad. I keep an eye out, an open mind. Watch the skies, watch the television, watch the papers. Be aware. Enid, Flint, Grand Junction. Hartford, Indianapolis, Jacksonville. (Even Jacksonville is cold; there’s concern for orange growers. Tiny fires smolder in endless groves.)

“It’s a fact, no matter how much we hate it,” Randall says, turning a page in his magazine. “No children.”

“I hear you,” I tell him, which is true. I do.

Kalamazoo. Lansing. Lake Placid.

But I don’t think he’s listening all that well, I don’t think Randall is up-to-date with what’s going on, despite his Harper’s, his Time, US News and World Report, Wall Street Journal. I suspect he’s a little deaf to what’s happening. I, on the other hand, am tuned in, am surrounded by the future’s promise—smart people, dumb students with the itch to get smart—and I don’t like ruling out possibilities, like I said, good or bad.

Minneapolis, Nashville, New York.

I know to keep an eye out, an open mind.

Oahu—not a city, but the Weather Channel lists it as such.

So, be aware, be patient. Wait for things to happen, look for situations to change. It isn’t winter everywhere.

Oahu. Oahu.

Matt Clark’s novel Hook Man Speaks (Putnam/Berkley, 2001) was chosen as the inaugural title for the Texas Monthly Author Series. When he died in 1998, at age thirty-one, Matt was coordinator of the Louisiana State University Creative Writing Program. His stories have appeared in One Story, Southwest Review, Alaska Quarterly Review, Gulf Coast, Flyway, and Yalobusha Review, as well as in the anthology Texas Bound. While a graduate student at LSU, Matt was fiction editor of New Delta Review, which now sponsors the Matt Clark Prize in his honor. This story, “The Last Eunuch,” is from Matt’s unpublished collection South/West.

Illustration by Katherine Villeneuve