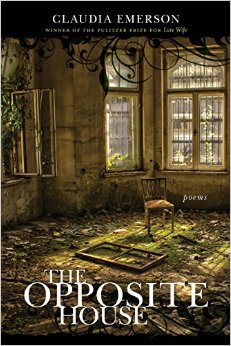

The Opposite House, by Claudia Emerson. Louisiana State University Press, 2015. $18, 61 pages.

Elegaic. There is no better word for this sixth collection by Claudia Emerson, a poet who died a few months before the book’s release. The title is taken from Emily Dickinson, whose words in the epigraph identify The Opposite House as a place of death, indicated by the house’s “numb look.” Though The Opposite House contains three numbered sections, only the second section is given a subtitle: “Early Elegies.” Thirty-four poems comprise the collection, and all have been published previously in places such as The Chronicle of Higher Education, The New Yorker, and Virginia Quarterly Review. The Opposite House identifies loss in multiple ways and locations. Some poems, in isolation, are optimistic, even light-hearted; who, after all, regrets the loss of smallpox or telephone booths? The elegy as a form celebrates as well as mourns. Emerson has known this for a long while; her second collection, Pinion: An Elegy, includes an introductory line from Stephen Foster’s song “Hard Times”: “Let us pause in life’s pleasures to count its many tears.” That epigraph could serve just as well for the present collection.

The book’s opening poem, “Ephemeris,” returns to the occasion of an estate sale, a setting Emerson has explored previously, in poems such as “What They Want” from Figure Studies, “Photograph: Farm Auction” from her Pulitzer-prize winning collection, Late Wife, and in “Going Once, Going Twice” from her first collection, Pharaoh, Pharaoh. In “Ephemeris,” a woman is left inside an empty home, having received insufficient bids for the house after selling off all the possessions. She is left with “a rented hospital bed / in the kitchen” along with “a borrowed coffeepot, chair, / a cot for the daughter she knows, and then does not.” Her loss is not simply material but cognitive as well. Still, the woman finds her situation “almost right” and is reassured by her body’s thinness. There seems rightness in the lightness of her sleep, which is like:

the shallow

sleep of a house with a newborn in it,

a middle child she never saw, a boy

who lived not one whole day (an afternoon?

an evening?) sixty years ago in late

August.

Like the no-longer-known daughter, the woman’s middle child has no name, yet he is “the nearer,” and, as the poem ends, she senses not only the lost child’s closeness but his need:

he is again awake,

his fist gripping a spindle of turned light,

and he is ravenous in his cradle of air.

The closing poem of the first numbered section, “Entrance,” bears a similar motif of a lonely woman, beginning, “Some evenings her own house convinces her / she is already dead.” The female inhabitant appears confused, cut off from the world:

The phone is silent

in its cradle, food tasteless, even salt dumb

grains of glass.

This woman discovers even

[h]er hair, her fingernails,

her nakedness against the naked floor, the body

unbathed for days, some days, not enough

to set the world back right.

In the second stanza, another recurring image appears: the snake. In the initial poem of Late Wife, “Natural History Exhibits,” Emerson also used the snake, setting up its symbolism of uncomfortable otherness. Here, in a childhood memory of the woman, the snake has eaten the eggs in an upper nest of the henhouse. She is “[t]oo small to see” but “feels the sleeve of its body well muscled / with eggs.” “[H]er mother’s fury,” she knows, will be greatest for the loss of the artificial egg left in the nest to encourage laying. She must kill the snake and regain the porcelain counterfeit, noting in the process that the real eggs “would have been more than enough / . . . for a pound cake.” This reversion to memory is the woman’s “entrance to another house,” and the reader realizes the woman will spend the rest of her conscious life searching out such houses, places of comfort that she can have “all to herself.”

The second section is the least emotional of the three. Eight poems identify something from our culture that we no longer have, most lost due to technology, such as the telephone booth and telephone operator. In “Cursive” she identifies the loss of cursive writing, the sole remnant being “the signature [. . .] / though poorly executed,” which she predicts will disappear once we are able to scan our fingerprints, a less forgeable signifier. The only recurring loss in this section is in the poem “Wisdom Teeth,” which she calls “the revenge / of the body’s forgetfulness.” Each of us must deal with them in our own turn, though they are all drawn “from the same old wound.” A shared nature of loss pulls the reader along, especially in this second section where the losses are conceptual rather than personal.

The titular poem (and three others in the third section) uses a structure that Emerson has not used in her prior books. The lines are double-broken, leaving each “line” in three parts, the succeeding fragments beginning immediately beneath the end of the previous:

This place:

a cavernous warehouse

of houses

dismantled,

cataloged,

reordered here

This drop shift is something I first learned from Denise Levertov’s work. Levertov’s poem “Her Sister” (Candles in Babylon, 1982) models this line, a technique which Levertov likely learned from William Carlos Williams (see, for example, “Overture to a Dance of Locomotives” and “To Daphne and Virginia”). This particular form relies on short units that allow the whole three-part line to stretch across the page without having to wrap or shift backward. In this poem, the house (rechristened “a cavernous warehouse”) represents death and the resulting dissolution, whether from “bone- / pickers rac[ing] / . . . for what / might be / salvaged to sell” or

daffodils blooming

like wild,

unmeant things

in what

appears an old field

without design

or sumac, which provides “its / own transfiguring / salvage.” Regardless of the image, the breaking down of the previous parts to be reused by the new is relentless, “slow— / unambiguous.”

Except metaphorically, this is not a collection exploring Emerson’s own battle with cancer. Unlike the poems of her first three collections (and much of her fifth), The Opposite House poems are mostly free from the recurring I. The use of the objective he and she rather than the personal I allows Emerson to write, not only from outside of her own body, but specifically from another’s point of view. This is the stance that Emerson abruptly shifted to in her fourth collection, Figure Studies, published in 2008, which uses a persistent they, conceding near the end to an ambiguous we.

The poems of The Opposite House are observational. Only a few section-three persona poems—“Rural Letter Carrier,” “Dr. Crawford Long, Discoverer of the First Surgical Anesthetic, and the Case of Isam Bailey,” “Irene Virga Salafia,” and “The Ocularist”—use the first person, but not in reference to the author. “Dr. Crawford Long” especially is reminiscent of Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess,” where the speaker of Emerson’s poem seems oblivious to the horror he commits in cutting off a man’s finger without his newly developed anesthesia just to prove that the “ether-laced cloth” was not a trick like hypnosis. The racial callousness of both the speaker and the slave owner creates another level of disconnect between the reader and the poem’s persona. Emerson writes the personas of these few poems carefully and with the idiosyncrasy inherent to each character.

In her first collection, Pharaoh, Pharaoh, Emerson wrote in “Cleaning The Graves” of the mother and her mother before that, concluding “I am descended from this / loss.” What matters, Emerson writes, is that readers continue to probe what is for meaning. Are we not all descended from loss? She concludes “Lock,” the initial poem of The Opposite Houses’s third section, in oblique contrast to Tennysonian motivation “to strive, to seek, to find,” preferring more fallible terms:

And while they can never

get close enough, they will never be any

closer than this to what it does not tell them,

and they are desperate for all that that might mean.

The Opposite House is an excellent collection. The poems will set intelligent readers thinking rather than hurrying on to the next page. There is neither pathos nor bathos in these honest observations of what it means to be mortal in an inconsistent world.

Stan Galloway teaches English at Bridgewater College in Virginia. His reviews of poetry have appeared in such places as Paterson Literary Review, Christianity & Literature, and Cape Cod Poetry Review. He also writes poetry and literary criticism. His books include Just Married, (unbound CONTENT, 2013) and The Teenage Tarzan (McFarland, 2010).