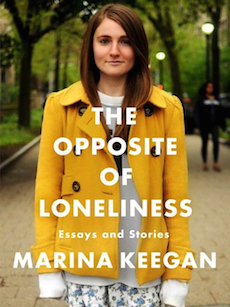

The Opposite of Loneliness: Essays and Stories, by Marina Keegan. Scribner, 2014. $23, 208 pages.

In the first essay in Marina Keegan’s book The Opposite of Loneliness: Essays and Stories, she writes, “We’re so young. We’re so young. We’re twenty-two years old. We have so much time.” But, in reality, Marina didn’t. Five days after she delivered a speech to her graduating class, her boyfriend was driving her to a party when he fell asleep at the wheel, hit a guardrail, and rolled the car, twice. Her boyfriend was uninjured. Marina was killed. Her parents, friends, and professors gathered her work with vigor, keenly aware of the brilliant mind that had left behind a body of work surpassing her years.

You can’t read The Opposite of Loneliness, which consists of nine essays and nine works of fiction, without feeling a bit haunted. The irony is overwhelming. There’s a certain type of roughness, a raw openness, in Keegan’s prose. She writes without pretense, without idealism, without the supposed wisdom that age and experience is meant to bring. Instead, she writes from that exact place she is at, young adulthood, a time of decisions and crossroads, uncertainty and hope.

Instead of answering questions, Marina asks them. And isn’t that approach more true to life, anyway, asking questions without finding the answers? “The notion that it’s too late to do anything is comical,” she says in her opening address to her Harvard graduating class. “It’s hilarious. We’re graduating from college. We’re so young. We can’t, we MUST not lose this sense of possibility because in the end, it’s all we have.”

Many young writers shy away from approaching issues that pertain to their own lives, struggling to write with a wisdom that is not their own in order to tackle global problems they have not yet encountered. There is a quality of goodness to this pursuit. But Marina writes with a voice that is her own. She realizes that it is in our youth that we choose the type of person that we want to be. Her stories touch on issues that young people, with our lives ahead of us, face every day.

In “Cold Pastoral,” a girl slowly, painfully uncovers the secret that the boy she loved was in love with someone else all along. In “Even Artichokes Have Doubts,” a class of graduates is about to sacrifice their passions at the altar of six-figure salaries. “What bothers me is this idea of validation, of rationalization,” she notes. “The notion that some of us … are doing this because we’re not sure what else to do and it’s easy to apply to and it will pay us decently and it will make us feel like we’re still successful.” In “The Ingenue,” a young woman who realizes that the man she is about to marry can’t be trusted, and her character thinks, “How utterly I’d been reduced. Mocked. Betrayed.” In “Winter Break,” a child navigates the messiness of her own romantic entanglements while watching her parents’ marriage crumble.

These are crises that ultimately shape our lives, and yet, so often, we only hear about them in hindsight. We hear from the perspective of the hardened woman who was once rejected, the middle-aged workaholic toiling away at a menial job he despises, the man and woman who no longer love each other. We ask ourselves what are we supposed to do now with the broken pieces of a wasted life and mourn over what could have been. But perhaps we should be asking ourselves these questions as Marina did, now—in our youth—with hope instead of regret. How do we keep our lives from breaking apart before it is too late? How do we make the most ourselves before we are forced to regret what we have done? How do we become the people we want to be? Marina was the type of person who strove to be the best version of herself. Her nature shines through in her work, and her poignant storytelling ability provokes her readers to question.

There is the occasional spot of awkward phrasing throughout the book, and one or two times I found myself wishing for more character development. Instead of interfering with my enjoyment of my work, however, these issues simply brought authenticity to the work. In several cases, Marina did not have time to self-edit, and this makes her stories and essays even more impressive.

In the midst of writing about the everyday, Marina tackles the universal. “Sometimes I think about what it would be like if there was actually peace,” she writes in “Song for the Special.” “Before the world freezes and goes dark, it would be perfect. The generation flying its tiny cars would think itself special. Until one day, vaguely, quietly, the sun would flicker out and they’d realize that none of us are.” These are the questions that plague us when we fall asleep. What will we do with our lives? Will it matter? What’s the point of it all, anyway? She pokes fun at the meaninglessness of our constant need for recognition, the exhausting, never-ending rat-race for wealth and power. “The thing is,” she says, “someday the sun is going to die and everything on earth will freeze.”

Marina recognized her own mortality and she was not afraid. She inspired a hope that can be shared by us all. “Sometime before I die I think I’ll find a microphone and climb to the top of a radio tower. I’ll take a deep breath and close my eyes because it will start to rain right when I reach the top. Hello, I’ll say to outer space, this is my card.”

Ashley Simon is a student majoring in sign language interpreting at Bethel College, Indiana. She is involved in the school’s honors program and has been writing for as long as she can remember. When she’s not studying her mind away, she enjoys drinking tea and longboarding around Mishawaka.