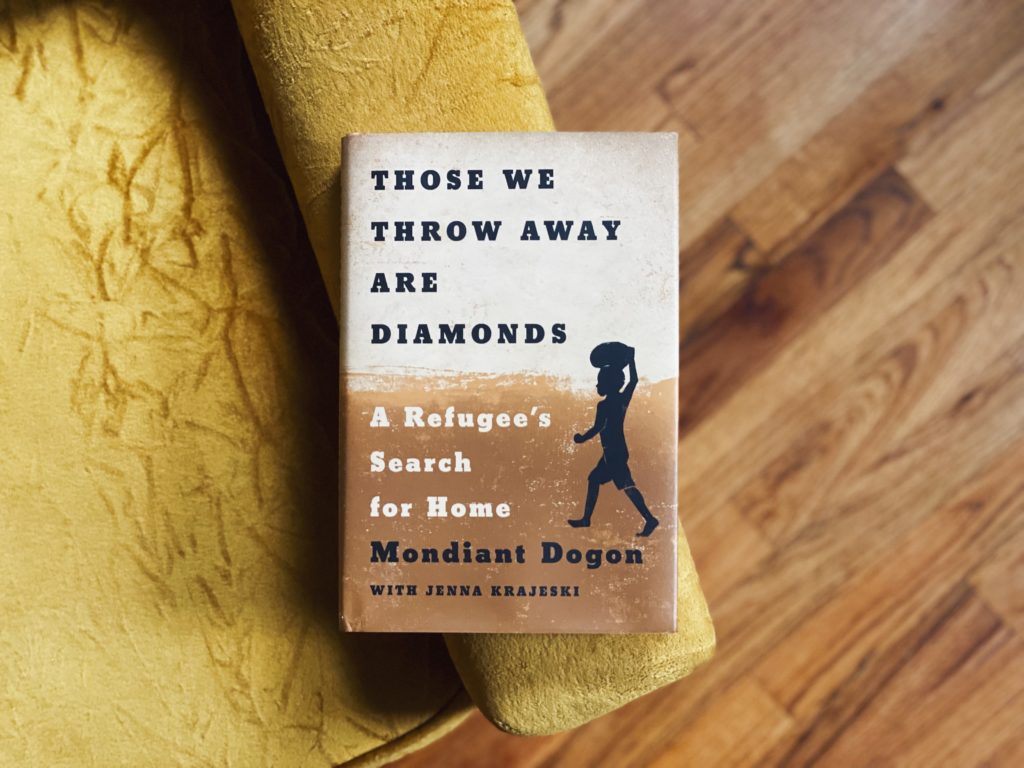

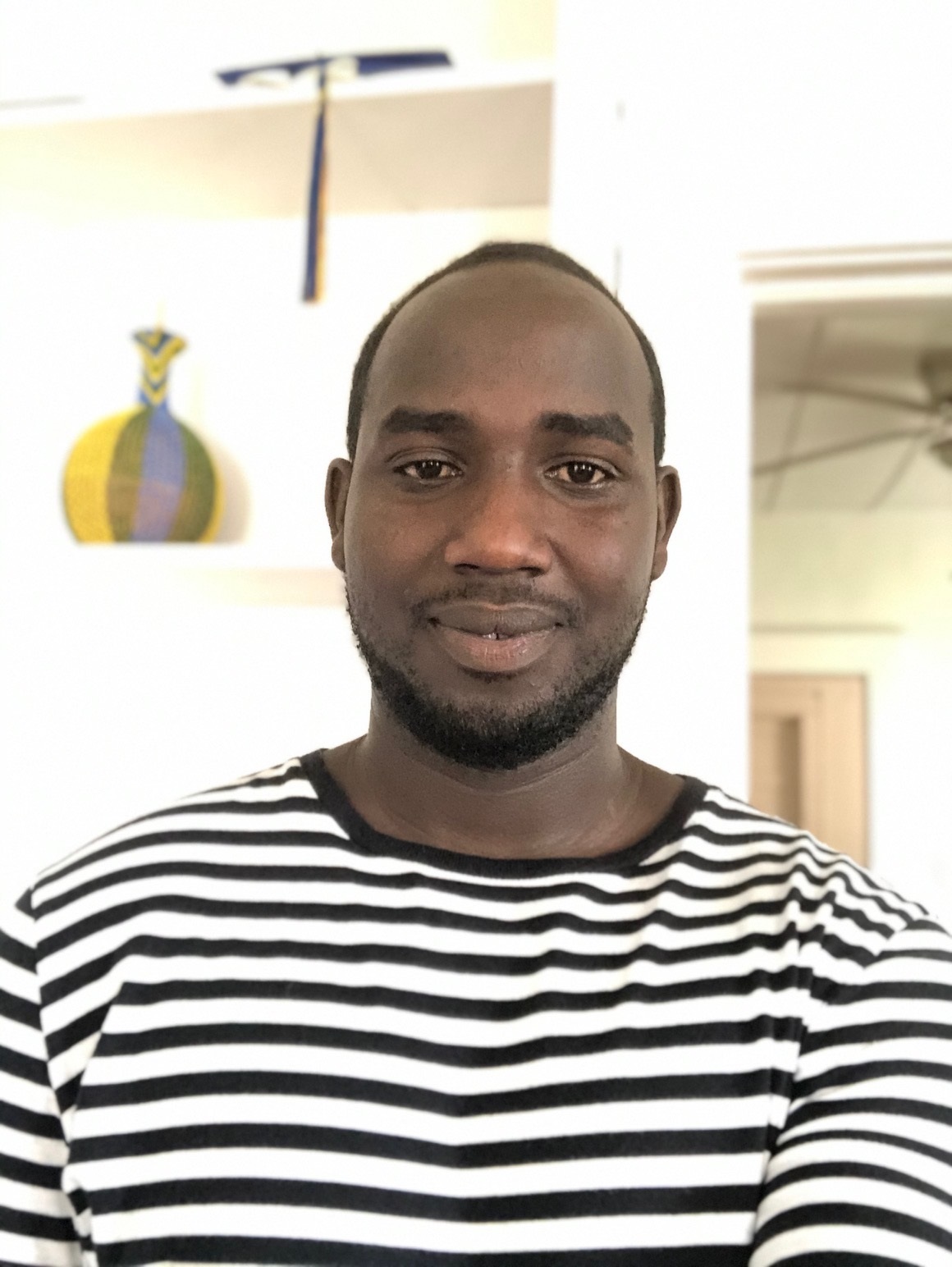

Mondiant Nshimiyimana Dogon is a Congolese author, human rights activist, and refugee ambassador. Born in 1992 into a Congolese Tutsi family in Bagogwe tribe in North Kivu province, he was forced to leave his home village, Bikenke, at the age of three because of the Rwandan genocide against Tutsis that spilled over into Congo. He has lived in refugee camps since 1996. In 2017, was able to leave Rwanda to attend New York University. He now lives in New York City.

Jenna Krajeski is a reporter for The Fuller Project whose writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, and The Nation, among other publications. She is the coauthor of Nobel laureate Nadia Murad’s memoir, The Last Girl, and was a Knight-Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan.

***

NEW ORLEANS REVIEW

Sharing stories about traumatic experiences is a hard thing to process into words. How does it feel knowing that this account of your experience is going to bring to light an entire group of people that have only been labeled as “refugees” and nothing more?

DOGON

It is traumatic to share this kind of story. Like my people, I grew up where silence was the main wound. It is a killer, and 90% of my people did not go to school, so they cannot read and cannot write, but 99% of them have been through massacres. They don’t want to share what they’ve been through because of what they’ve experienced; they live in fear that sharing their stories will keep them from getting resettled in America or somewhere else. Silence was not easy, but for me it was just as harmful. Writing and sharing my stories was the only way that I could begin to work through that trauma.

NOR

How has that shame into keeping your story and your status as a silent refugee shaped the way that you tell stories now? Have you considered becoming a motivational speaker?

DOGON

Absolutely. After I finished my undergraduate degree in 2016, I went between refugee camps to connect the stories of war and suffering. These stories were mostly held by women, women who didn’t go to school, but they all had deeply traumatic stories that they were hesitant to share. I went from camp to camp to share these stories and continued sharing their stories and collecting others. I had the opportunity to mobilize and encourage other refugees in Rwanda to continue speaking of their experiences.

NOR

This is your first novel. Do you plan on writing more novels in the future?

DOGON

That’s what I plan on doing. Right now I’m working on two novels. One is about the stories that the women shared with me and the experience of other refugees, and the other is an account of the violence in the Congo.

NOR

What has the process of drafting this book and getting your experiences down permanently taught you about yourself?

DOGON

Writing my book has shown me that it was the only way that I could embrace my past, my identity as a refugee, and how well I know myself. It has given me the opportunity to learn about myself and accept my past in a way that has only been beneficial.

NOR

Early on, you speak of not telling others that you were a refugee, instead letting your peers at NYU believe that you were from a wealthy African family. How did this part of your life shape your identity and how you presented yourself? Do you regret not speaking up sooner?

DOGON

I don’t regret anything. I believe that everything has a time and place, and these are the moments for them to know my story now.

NOR

I don’t want to focus on retelling the standard accounts of tragedy. Could you think of any moments that made you want to continue when it could have been easy to give up?

DOGON

In the refugee camp where I grew up, the other men around me would never keep going to school. Instead of chairs and desks, we sat on stones. Instead of paper or books, we scratched notes into our skin. So many people gave up. For me, my education was the chance for me to get out of that situation, so I never gave up. There were so many people who did give up because of how hard it was.

NOR

In a bit of a tone shift, do you still find comfort in trying to count the stars when you think about Gihembe [Refugee Camp] or when you’re just having a rough day?

DOGON

Because of the skyscrapers and lights, New York City is too bright to see them most of the time. Sometimes I go to the Brooklyn Bridge or Central Park at night to sit and just interact with nature. The stars were the light in my life before, and now there is so much other light everywhere.

NOR

Do you have any hope of helping other refugees tell their stories, even if it is just giving them the confidence to share?

DOGON

Absolutely; my story is for all refugees, all over the world. I have never been to Myanmar or anywhere else that struggles with refugees, but their stories are all similar. I have founded the Mondiant Initiative to support refugees all over the world. I started it in Rwanda, but I am hoping to expand globally. My advice for anyone in refugee camps is to just be who you are, no matter what. Try to keep that hope that there is good in the future. Chinua Achebe said, “When the sun shines, it shines first on those who are standing,” so I try to tell all refugees I meet to just keep standing, that the sun will keep shining on you.

NOR

Thank you so much for joining me today. Is there anything you’d like to share as a final note?

DOGON

The Mondiant Initiative is currently fundraising for refugee camps, so this is the stage for many people to become aware of the conditions and needs of these camps. My parents did not go to school, nor do most people in refugee camps. They’ve been through so many traumatic experiences, so I want to bring something to people so that they can learn what they want to, even if they already know how to read or write. They need an outlet for creativity, so I am planning on building a Creative and Socio-Emotional Learning Center. If people are interested in donating, they can find the links through our website. Thank you so much for your time!

Melanie Hucklebridge is a budding editor that is temporarily residing in New

Orleans, Louisiana. She is currently in her last year at Loyola University New Orleans

as an English Writing major with a minor in Latin American Studies. Donning many

hats, she has experience in academic editing, in the form of academic articles and

textbooks, and essay writing. She previously worked for Where Y’at, a New Orleans

based entertainment magazine, as a content writer where she focused on restaurant

and bar guides, as well as special interest pieces. A self-proclaimed “plant mom”,

she spends most days discussing the intricacies of Renaissance poetry or explaining

constellation myths to her host of plants or reading in parks during thunderstorms.

+++This interview was edited for length and clarity