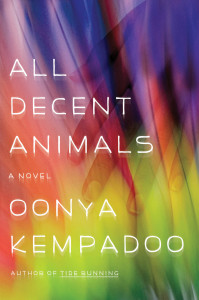

All Decent Animals, by Oonya Kempadoo. FSG, 2013. $26, 272 pages.

During Carnival in Port of Spain, with loud Mama look a boo-boo tin pan, rum in everyone, close friends throw answers back and forth to the question: Where does the name “calypso” come from? They discuss its Caribbean, French, Spanish/Venezuelan, and West African origins. There is no easy answer. It is shaped out of cultural congress, it has come together from across diverse sounds and styles into an artistic interpretation that here resonates profoundly with the human experience of these Trinidadians. In this scene from Oonya Kempadoo’s third novel, All Decent Animals, the friends could just as well be talking about the very story world in which they exist because a similar pattern of coming together underpins this book, a weaving of peoples, cultures, and old and new worlds.

In an interview during her University of Iowa’s International Writing Program’s 2011 fall residency, Kempadoo addressed the question of what is the best thing about being a writer in Grenada: “The scale of the country and the interconnection between social issues, different classes. The ability to interact on many different levels in such a small society, for me is one of the best things. Because you’re able to observe many things that you wouldn’t be able to otherwise in a big society.”

Kempadoo’s character Ata is such an observer. At its core this is the story of Ata’s journey to become a writer. Ata evolves, emerging as both an artist from her work in Carnival costume production and freelance graphic design, and as a writer from life experiences among close-knit friends. But much like a sexual revolution, the roads and signposts of the journey are not always clear to oneself; it is not until late in the book that Ata realizes the artistic transformation that has been underway inside of her.

The story pivots on Trinidad’s Carnival, the lavish colorful festival of excess to celebrate final indulgences before Lent. In Kempadoo’s style of writing, the text is a sensory experience: textures, fabrics, costumes, drum rhythms, colors of all vibrancies, tastes, heat, samba, sweat, sex. Often the text has an electric dialect of Trinidad, along with mesmerizing comparative language pulled from the locale. The “hustle and knivery” of the town. A “water drum beat in her belly.” A close friend dying from AIDS talks to a doctor about his ending, and words like departure and euthanasia “slide around on the floor like wet slugs.”

The first two chapters cover eight years, opening with Ata’s arrival in Port of Spain to work in a costume factory, “in the cussing, roughing, gnarly hell of carnival production,” under a gay man named Francisco. Very soon there is a big time shift of four years, and the story checks in with her progress: a job in an office, a place of her own, and a super close friendship with Francisco. Francisco has been the victim of gay bashing – “a bunch of fellas had stoned him as he walked home”–and, in fear for his life, he leaves for England to live with an aunt. In the wake of his sad departure, Ata goes to a party where she meets Fraser and a French man Pierre. Both of these men are central to Ata’s creative journey for the remainder of the book. Fraser is a “returnee” (has returned to Trinidad), “a big creative lump of an architect, from good Trinidadian middle-class stock, properly educated in England.” Before long Ata has sex with Pierre, and chapter three opens with another big time shift, four years later, Ata and Pierre living in a house up on a hill overlooking Port of Spain and the Gulf of Paria.

From here, the narrator sets in motion a more paced telling of the story. It feels that we have arrived in the story’s present time. Right away there is a flash forward to a scene in which Fraser is suffering dialysis treatments. Some flashbacks, flash forwards, and shifts in point of view are confusing at times and disrupt the reading experience—perhaps simply because these are not marked as such—but each puts the camera on a subject important to the story, and so Kempadoo has clearly not set out to keep the reader off balance. The point of view shifts occasionally to a taxi driver, which is engaging and meaningful because it opens a window to perspectives from a native Trini, someone just beyond her circle of friends. Ultimately this is a linear story of Ata’s artistic rising. But the narrator at times seems to struggle with form given the ambitious breadth of complex topics.

For Kempadoo, there is much emphasis on place in her characters. Kempadoo, who now lives in Grenada, was brought up in Guyana, and lived in Europe and various islands in the Caribbean. Kempadoo has created a similar background for Ata: Ata defines herself as “a nonbelonger” of either Europe or the Caribbean, while “unretractably entwined” in all of these places. Ata writes of herself: “Growing up hearing about Caricom ideals and global citizenship, Ata felt ‘Caribbean,’ not Dominican, not Guyanese, not Trinidadian—a true no-nation.”

A sexual revolution is underway for Ata, too, like a ribbon in the helix of her artistic journey. The tug of this ribbon occurs at times that seem just right in the story, well-placed signals of change.

In a poignant moment between Ata and Fraser, who is too ill to rise from bed, Ata asks, “When in life do we know the full meaning or reason—as the thing unfolds?” Like the question of calypso’s origin, there is no easy answer. For Kempadoo’s characters, the place to look is where things connect; where there is the weaving of people, the coming together of them, the falling apart, the inevitable loss, the assemblage of so many unique threads of experience.