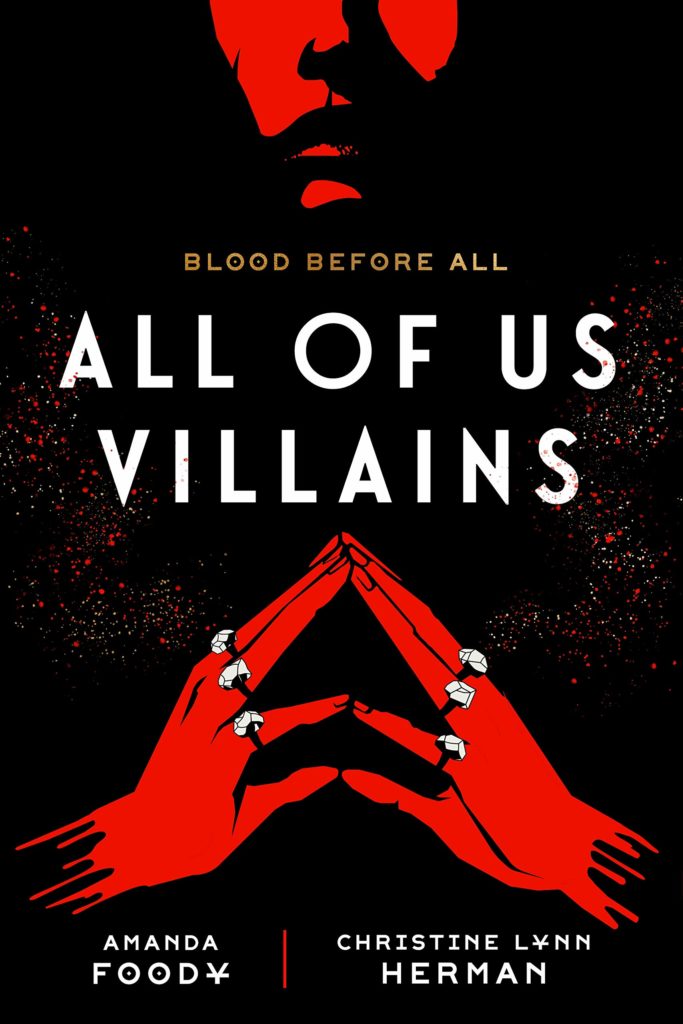

All of Us Villains by Amanda Foody and Christine Lynn Herman. TOR Teen, 2021. $18.99, 384 pages.

The time to embrace your monstrousness has come. Amanda Foody and Christine Lynn Herman’s first installment in their new series, All of Us Villains, gives us the disturbing death tournament trope sparked with Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games series, paired with the addition of a powerful magic system. If this short comparison piques your interest, the more sinister additions of blood sacrifices fueling curses, among other wicked acts, will plunge you deep behind the veil.

After the publication of a book that exposes the secrets surrounding the gruesome tradition, the city of Ilvernath is plunged into media attention as the Blood Veil tournament draws near. Self-proclaimed or otherwise, the villains of this story are simply defined by their willingness to do anything and everything to achieve power over the high magick supply. Of the seven families, the champions are picked because of their legacy, due to their need to change the way they’re seen, out of necessity, and out of what they believe is the greater evil – but regardless of their sacrifice, there are only four who truly are clouded by their own desires. Told from the perspective of the four main villains, it is a violent tale of betrayal, romance, and the realization that someone must be “the most villainous of them all.”

The alternating perspectives throughout the novel present an interesting take on how the tournament affects each character. While the novel only followed the stories of four of the seven champions, Foody and Herman do an excellent job at making them morally gray enough that your own thoughts on villainy are swayed. Alistair Lowe, a self-proclaimed monster, is the first villain to whom we are introduced and the one with the most compelling story arc. Born and bred to continue the Lowe legacy of wining the Blood Veil tournament, Alistair’s inner struggles of revenge and true wickedness come into play. After all: “Monsters couldn’t harm you if you were a monster, too.” The Lowe Champion is the most dangerous of the characters, slowly becoming more unstable as the narrative continues and progressively becoming my favorite of the villains.

The shifts happen on a chapter-by-chapter basis and often go back over the same information from different perspectives. This has its perks, such as when characters react to a death or a particular news event, but it is easy to get lost between chapters and forget which character’s perspective was in focus. When moving between the perspectives of two of the champions, specifically Gavin Grieve and Alistair Lowe, their similar patterns of power struggles can get muddled together. These moments of confusion only appeared toward the end of the narrative, once all four of the voices were in the thick of the tournament and experiencing the same environment and events.

The topic of death is heavily prominent throughout the narrative, which does not come as a surprise, but the way it is handled does set it apart from similar stories. Unlike the victors of Panem, the villains of Ilvernath are not averse to the ideas of dying or killing before they’re presented with the reality. Isobel Macaslan, the paparazzi favorite of the Blood Veil, even goes as far as stealing a curse and giving herself a severe disadvantage for a chance at winning, because even then, “if she did, then she would die a champion.” It is echoed by Briony Thornburn, Isobel’s former best friend, being willing to kill her own boyfriend should they both be named champions because they “were both loyal to their families; they wouldn’t forsake them, no matter what they felt for each other.” Even in her later search to be a hero, Briony is faced with a hard truth integral to the overall story arc of the book: “No one in here is a hero—least of all you.” The level of brutality is unusual to see in a Young Adult book, especially as the YA category is more geared toward teenagers. However, when the lesson is that there are monsters in everyone, even if you don’t realize it, it feels like a unique inclusion to the genre. Some may see it as a welcome change to the savior complex that we saw in characters like Katniss Everdeen.

Unlike many death tournament narratives, in Villains the media is involved in the events leading up to the tournament. Foody and Herman perfectly capture the nature of social justice warrior and performative activist thought processes by the small introductions of tourists and protestors that flock to Ilvernath after the release of the novel A Tradition in Tragedy that explains the tragedy of the Blood Veil. Even when they target the specific champions instead of the tradition as a whole, it reeks heavily of the real-world applications of performative activism that plague social media sites like Twitter. Instead of trying to find ways to break the curse, tourists flood to Ilvernath to harass the teenagers being sent to war, chanting, “YOU’RE NOT ABSOLVED FOR THOSE WHO DIED!” at them. Isobel and many others who echo this sentiment at the performative activists are right in saying, “Nothing these protestors did or said would change that.” Traditions are not broken overnight, but by the action of breaking standards and changing the way that the tournament is played. Even those ignored by the media, like Gavin Grieve, take extreme measures: “He’d mutilated himself just to make Ilvernath take him seriously.”

This book highlights the necessity of villains and how there are always monsters hiding behind the scenes. The ending of the book did not come with a neat resolution to the story or even the breaking of the curse, but with a rather unsatisfying revenge scene. The traditions around the Blood Veil aren’t what they seem and the champions all enter into a cycle of betrayal and gory revenge, but they do all come to the conclusion: “Better to play a villain than a victim.” The sudden plot twist at the end and the numerous loose ends that were left unresolved will hopefully be cleared up in the sequel, planned for release in 2022, but until then it is fitting that such a vicious narrative should leave its readers with a sense of confusion and bitterness. It is a terrifying tale that plays off the villain trope, which can feel overdone but, in this case, has established itself as something unique. There is no caricature of a specific group to make a good villain here, only things that we don’t wish to recognize as being truly villainous, like protecting one’s legacy. There is one line that accurately describes the entire book: “I think, deep down, some people don’t want their stories to have happy endings.”

This review was based on an uncorrected, advanced reading copy.

Melanie Hucklebridge is a budding editor that is temporarily residing in New Orleans, Louisiana. She is currently in her last year at Loyola University New Orleans as an English Writing major with a minor in Latin American Studies. Donning many hats, she has experience in academic editing, in the form of academic articles and textbooks, and essay writing. She previously worked for Where Y’at, a New Orleans based entertainment magazine, as a content writer where she focused on restaurant and bar guides, as well as special interest pieces. A self proclaimed “plant mom”, she spends most days discussing the intricacies of Renaissance poetry or explaining constellation myths to her host of plants or reading in parks during thunderstorms.