That’s a lovely way of putting it…

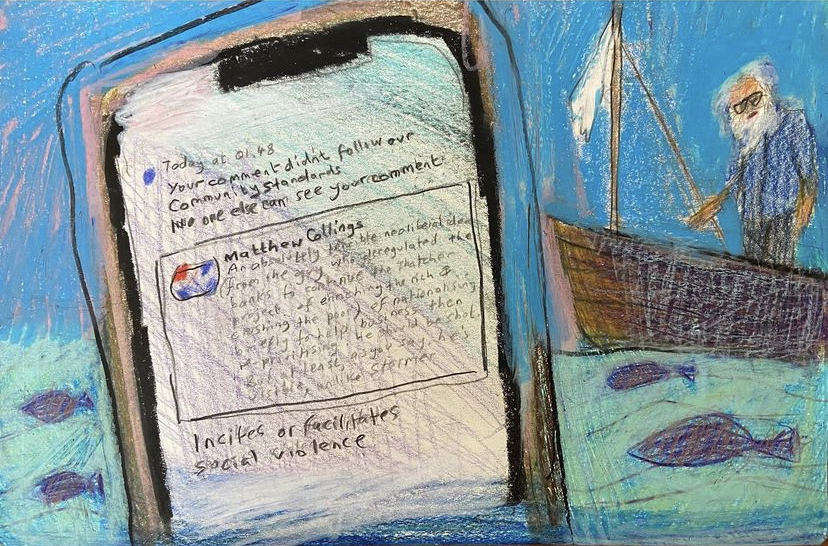

In Parts 1 and 2 of this three-part piece, I addressed Matthew Collings’ human-centric approach to art history and the ectoplasmic vibe. In Part 3, I am thinking about how the drawings function as works of art. Or are they works of illustration? Does this distinction matter?

Inventive Realism

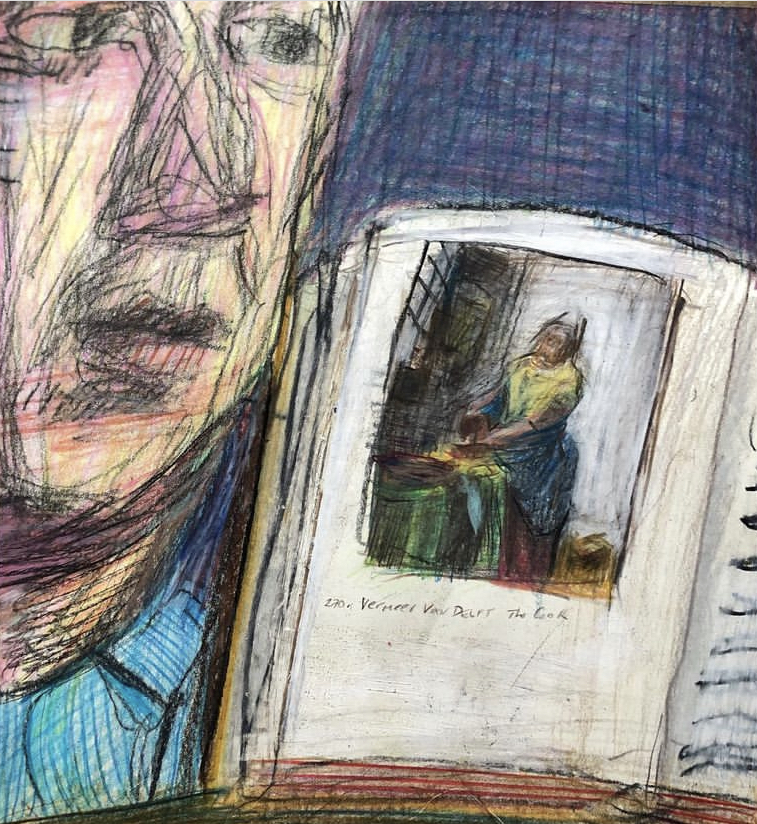

Collings’ drawings straddle art and illustration. There’s a lot of blah blah blah out there about the difference between illustration and fine art. Many distinctions have to do with market value and the artist as “brand.” Illustration is generally considered art made in the service of an existing story or idea. One could say that Matthew Collings is illustrating the history of art, but that’s not exactly true. He is materializing his impressions of the stories of art he has collected in a lifetime of studying it, thinking about it, and making it. Because he makes these drawings without a foreplan, they are hardly in the service of something already formed externally. The practice of categorizing artwork as fine art or illustration is a human-built system, separate from the internal drive to create. Were cave paintings art or illustration? It didn’t matter.

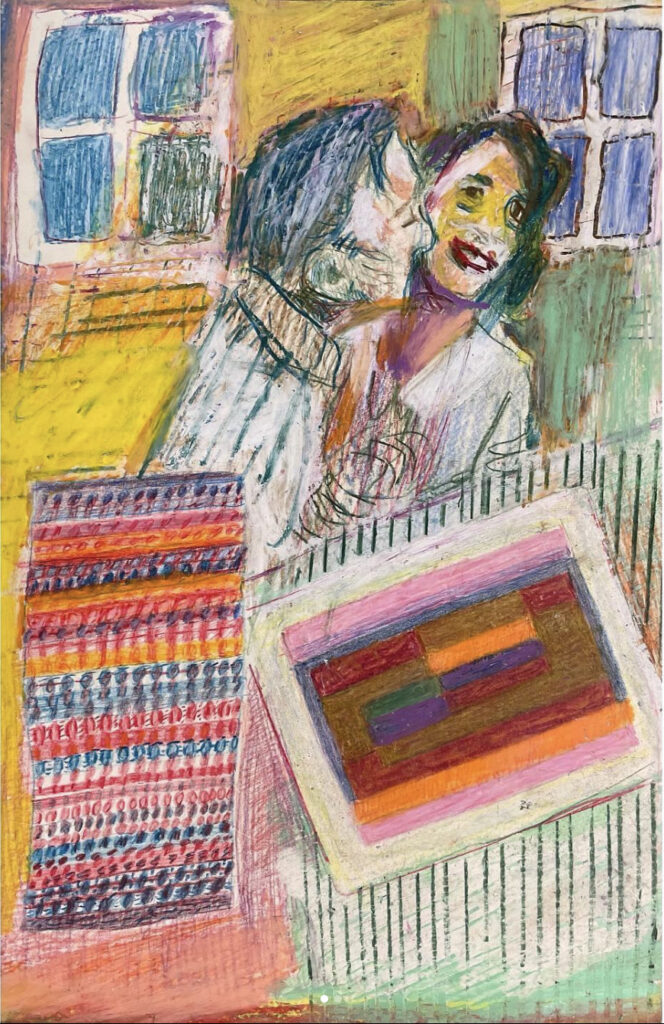

In one drawing, Collings positions artist and illustrator side by side. The drawing, posted on Instagram, is captioned, “Eric Ravilious and Alice Neel on a drawing holiday in the South Downs after Eric’s plane was lost over Iceland in WW2 and Alice died of cancer in 1984.”

Ravilious was a “British painter, designer, book illustrator and wood-engraver.” Alice Neel, currently the more well-known of two, was an American painter of the same era. In reality, Neel and Ravilious’ lives did not intersect. I asked Matthew Collings in the comments on Instagram if there is a connection between the two artists. He responded, “they’re both great at inventive realism.” I had never heard the term “inventive realism,” nor did I find anything when I Googled it. I thought about his impulse to put these two artists together and about the tone of the drawing.

Some people consider illustration a lower art form than, say, oil painting. In the drawing, the artist and illustrator coexist, enjoying the outdoors. Outdoor scenes are rare in these works; maybe because most art is made and displayed indoors. Here in the outdoors of the afterlife both artists are free of market-driven categories and echelons. In his own studio practice and in these drawings, Collings ignores some notions of how art is made and where it should go. These drawings, art or illustration, tell a story in the very medium it addresses: art and in a style I now think of as “inventive realism.”

Material World

What does it mean for an artist to draw on A5 paper with colored pencil? (A5 paper is the standard equivalent to 8.5 x 11 paper in the US). To draw on A5 paper is to shirk more highbrow art supplies like oil paint and canvas, to choose instead this vernacular material. Artists who have used non-precious art supplies (or office supplies) know that with these shifts comes a kind of freedom. Many artists experience trepidation standing before a blank canvas with tubes of oil paint, the history of painting breathing down their necks. Regular paper and colored pencils are the humble art supplies of hobbyists and children. And there is something childish or crude, possibly unpretentious about the drawings, and yet they hold a viewer’s attention because of complex layering of color, high-energy line work, and dense compositions.

The Ecstasy of Color

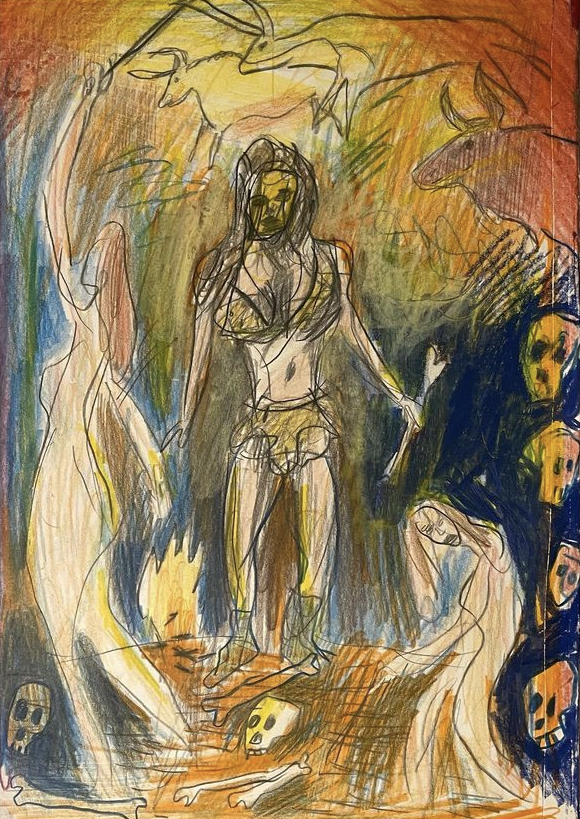

Matthew Collings’ art history drawings rely heavily on color as a device for establishing mood and tone. The laying of color gives the drawings a painterly weight and this makes sense. Collings’ studio practice is dominated by painting and his art writings reveal his complex understanding of (and dare I say faith in) color. One drawing is titled or captioned,

A common misconception about art that focuses on colour values, is that it’s “academic” – it’s not, it’s ecstasy – Josef and Anni Albers embracing with joy and laughing – a woven rug by Anni and an oil painting by Joseph.

The emotional tone in this drawing, joy, is almost itself the subject matter. The two figures are embracing, kissing and smiling, flanked by two windows, their work on display. The drawing celebrates color but also joy in partnership.

The strategy and organization of color in these drawings could trace back to Collings’ abstract paintings made in collaboration with his partner Emma Biggs, a mosaicist. When I first came across their paintings as a young artist, one thing that struck me as unusual was the fact of the painting being collaborative. How could an artist successfully drop individuality or ego and work cooperatively to create a unified vision in a single work? Maybe “the ecstasy of color” can drive an artist toward enlightenment, maybe color can literally promote harmony, a reality of complex and functional coexistence.

Art Life

Unlike versions of art history that prioritize organizing and straightening up something as sprawling and deep as the existence of art, Colling’ drawings reveal the messiness of art and where it intersects with the messiness of being a person.

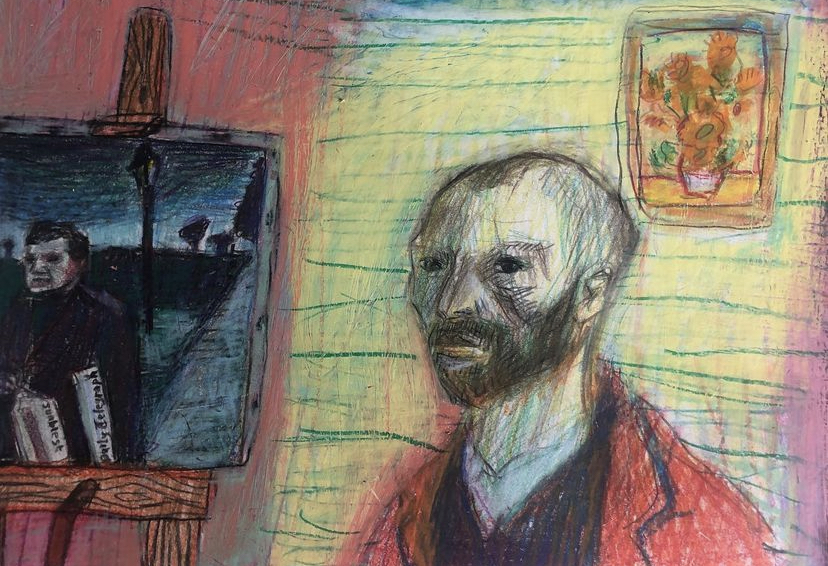

One drawing is based on a familiar portrait of Vincent van Gogh, a well-know still life in the background. There is a time-warping painting in progress on the easel depicting Francis Bacon who was born about ten years after van Gogh’s death. The full caption reads,

In his Arles studio, Van Gogh paints Francis Bacon in 1963 on the way to work. Francis exudes a fabulous aura of horror wherever he goes, and carries a packet of Sunblest sliced white bread for toast, and his regular paper, the Daily Telegraph.

These drawings don’t necessarily tell the facts but they tell the truth–or truths, plural. One truth contained in these drawings is that art connects us across the globe and across lifetimes. Some of my favorite drawings depict a single artist in the process of making art, in concentration or reflection.

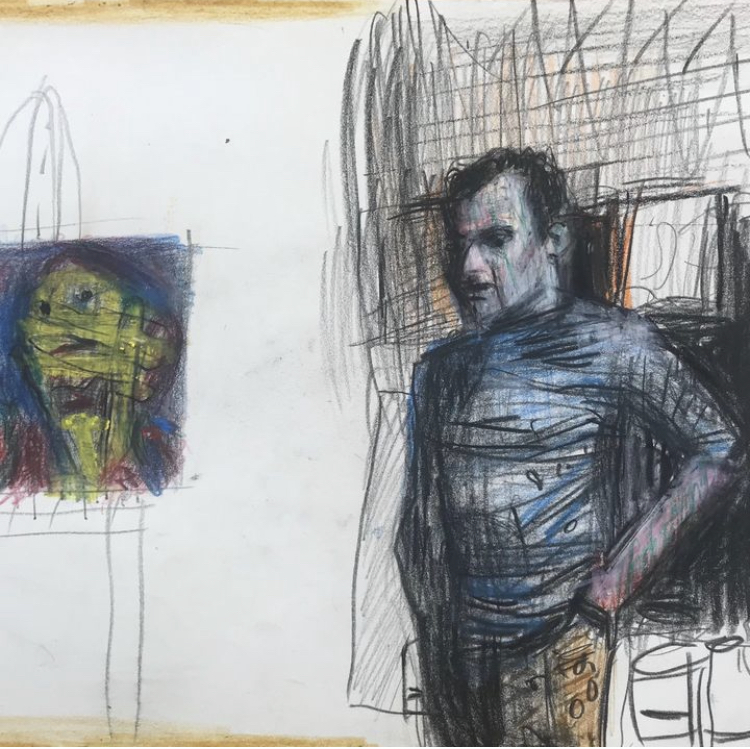

Frank Auerbach pauses, hoists his pants a little. He doesn’t look at the painting on the wall. He seems to be staring at something to the lower left of the viewer, or staring into space, his mouth a little open. There is devastating weight in this figure, and I find it hard to put my finger on where that weight lies exactly or how a bit of colored pencil can be so moving.

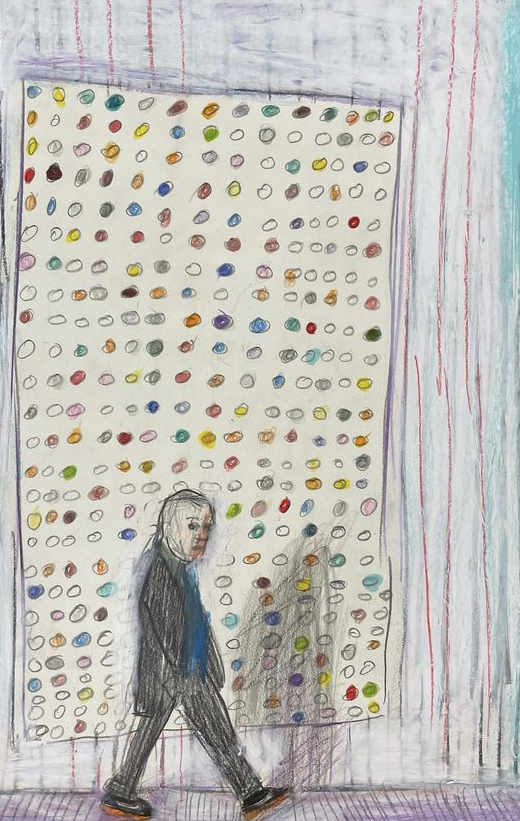

Damien Hirst is alone. He is not working but walking past his own painting, a grid of colored dots. There is a remoteness, a visual and emotional distance in this drawing that stands out against the others.

A drawing of Titian borrows its palette from Titian’s paintings.

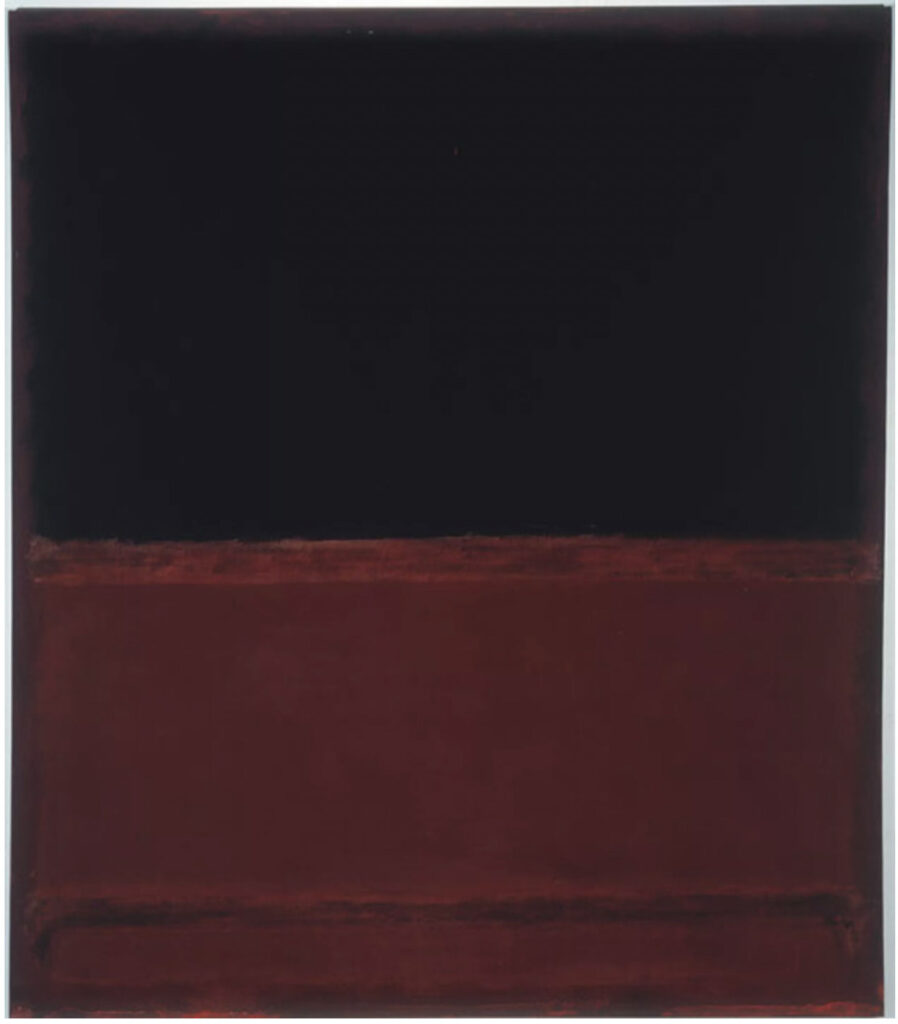

While some of Collings’ drawings are fantasies, others are moral tales based on facts. Collings made a drawing of Mark Rothko and captioned it:

Big moment – Rothko suddenly realises he can’t stand the idea of his big red paintings commissioned for the restaurant in the Seagram building being used merely as a backdrop for rich bastards eating their meals – he’s not gonna take it any more.

Rothko dined at the restaurant with his family prior to the completion of the Seagram commission. (A Jackson Pollock painting was hanging on the wall as a space-filler until Rothko’s paintings were complete.) After the meal. Rothko reportedly said to an assistant, “Anybody who will eat that kind of food for those kind of prices will never look at a painting of mine.” While this incident would probably not be mentioned in a traditional art history textbook, one could create an entire college course around it: Conflicts (Internal and External) in Art. For me a unique value of these drawings and Collings’ approach to addressing art is that they get at the most elusive part of all of it: what art means to be an artist and to live a life close to art.

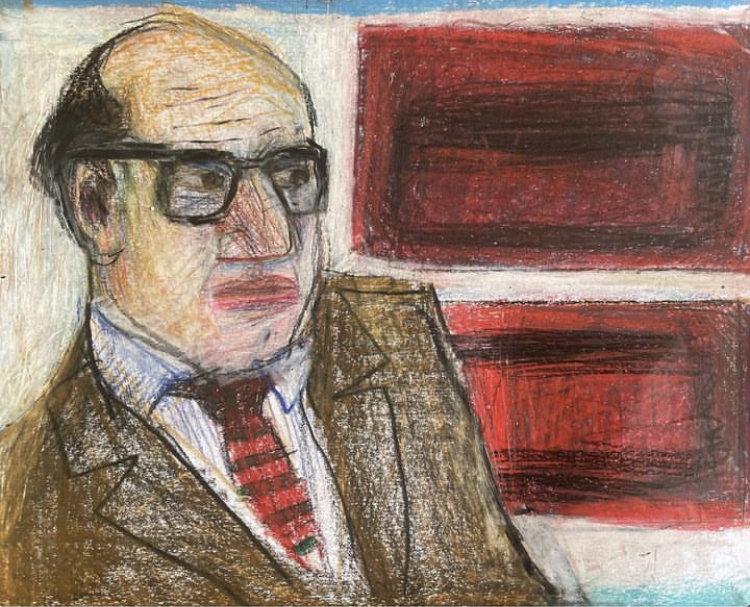

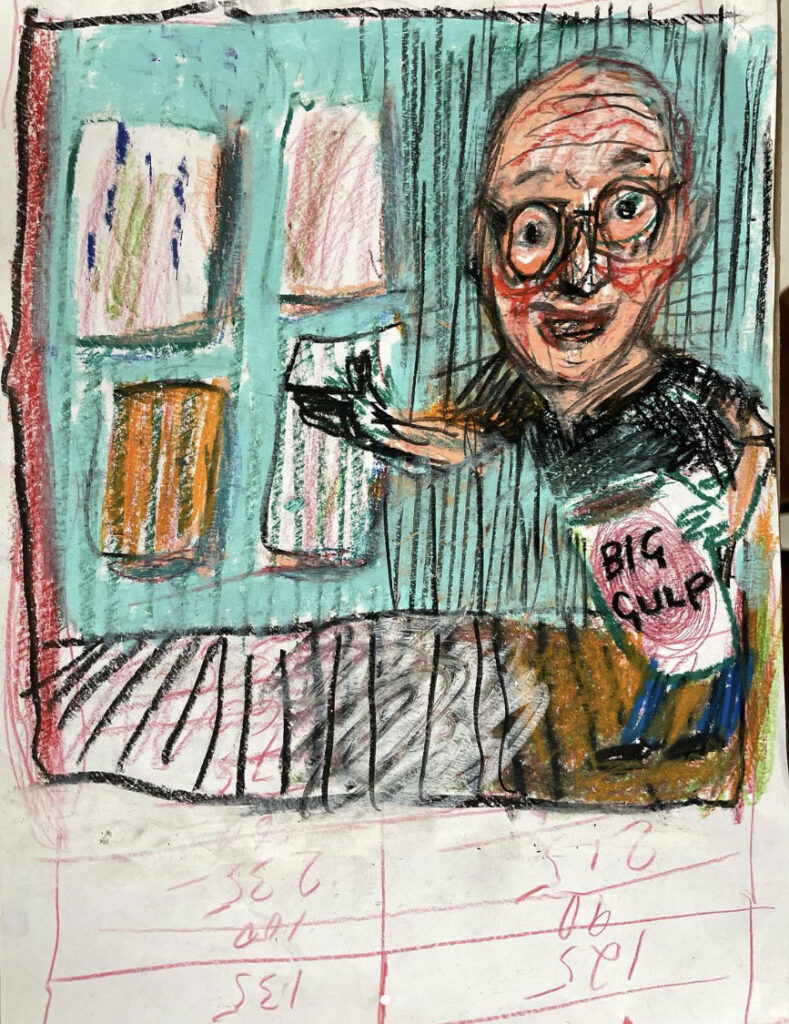

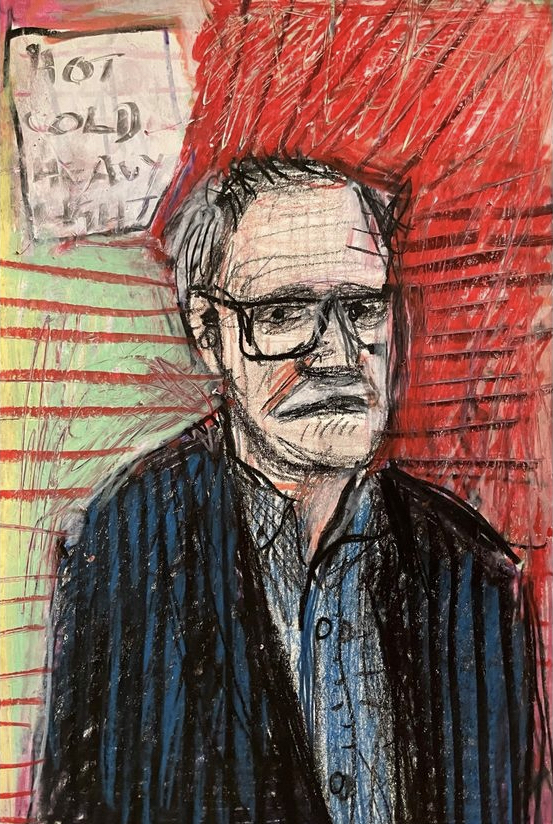

Collings’ story of art also includes critics and art writers. A drawing of New York art critic Jerry Saltz captures the exuberant author with his famous Big Gulp coffee. Collings posted a striking portrait of New Yorker critic Peter Scheldhal shortly after his death in 2022.

Art Life

I was nervous the night before I met Matthew Collings on Zoom. His career has covered massive territory so far; I felt intimidated and under-prepared. I planned to focus on the art history drawings but kept getting distracted in my reading because Collings has done so many things. The next morning I waited in the virtual meeting room. When his camera came on, he appeared smiling broadly. I told him that I was nervous, because, his practice was so vast; he was an artist, a writer, an “art personality” and…”anything else?” I asked him.

“I was also a kidnap victim,” he said, and related the story of how he ran away to Canada when he was 14 years old but officially it was considered a kidnapping. He was collected in Canada and returned to the UK, a swarm of press waiting at the airport. Matthew Collings is also a brilliant icebreaker. We talked for just over an hour and at one point, he excused himself and got up. I heard him shout, “Em! The door!” His partner, artist Emma Biggs, was expecting visitors. When he returned to the screen he said, “For five minutes someone’s been banging at the door.”

EF: I love that they were banging and not knocking.

MC: Well, they were knocking. They went from knocking to banging.

Something about this moment in our conversation stuck with me, so later I imagined the scene on my screen drawn on A5 paper in colored pencil, “Matthew Collings gets up from an interview to answer the door where visitors have come to see artist Emma Biggs at home.” Collings makes the story of art quotidian and scared, vast and inclusive, vivid and real. I asked Matthew Collings two final questions:

EF: What do you think makes a good person?

MC: Well, Socialism…

EF: What do you think makes a good artist?

MC: It’s got to be authenticity really.

Authenticity had come up earlier in our conversation when Matthew Collings said “I do see genuine authenticity and freedom, the potential for it, in art. That is my attraction to it.”