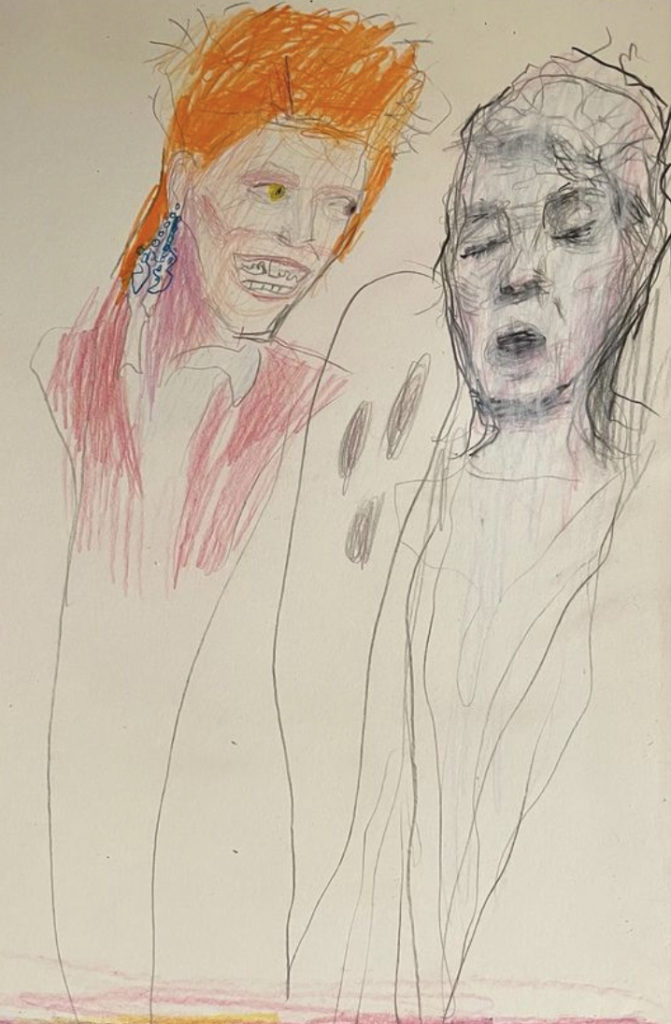

Joan Mitchell’s studio in the 1950s. “Heroes-era” David Bowie is there with her. So is Louise Bourgeois, and Claude Monet, partially translucent, standing behind Joan Mitchell’s dog. A new painting hangs on the wall under spotlights.

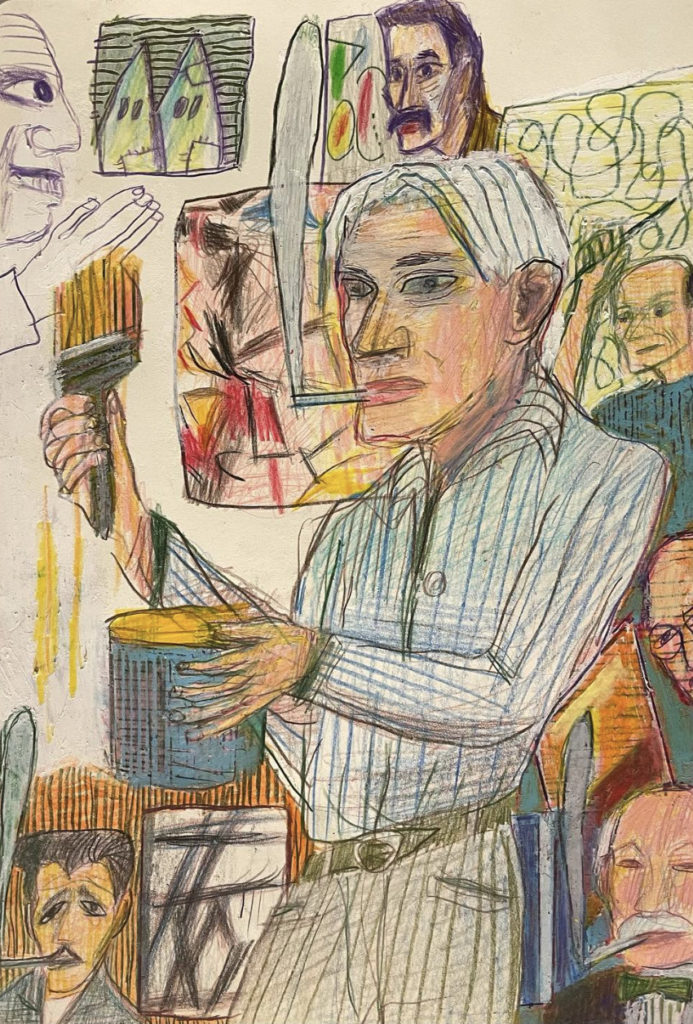

Since 2020, Matthew Collings has made over 2000 art history drawings in colored pencil on A4 paper. Collings is a British artist, art-writer, TV personality and, as I learned in our video conversation last month, a one-time kidnap victim. He posts the drawings on Instagram shortly after making them. The drawings are usually accompanied by a title or descriptive caption, some of them long enough to tell a story. They are sold through Artist Support Pledge an art community-marketplace. Eventually, images of the drawings will be edited into a book, though Collings’ plans around that are still forming.

Art History 101 textbooks like Gardner’s Art Through the Ages and H.W. Jansen’s History of Art tell the history of art, a general consensus that follows the history of humans. In these texts, certain works of art are used to illustrate various movements, milestones and “isms.” In 1950, E. H. Gombrich proposed a slightly more human approach in The Story of Art. He wrote:

“There is really no such thing as Art. There are only artists.”

And yet, to accomplish the task of writing an academic text, Gombrich needed to summarize, organize, put artworks and artists into labeled drawers, distill the zeitgeist and stick to the facts. The Story of Art, like other well-known texts, could be summarized:

“There is really no such thing as Art; there is only context.”

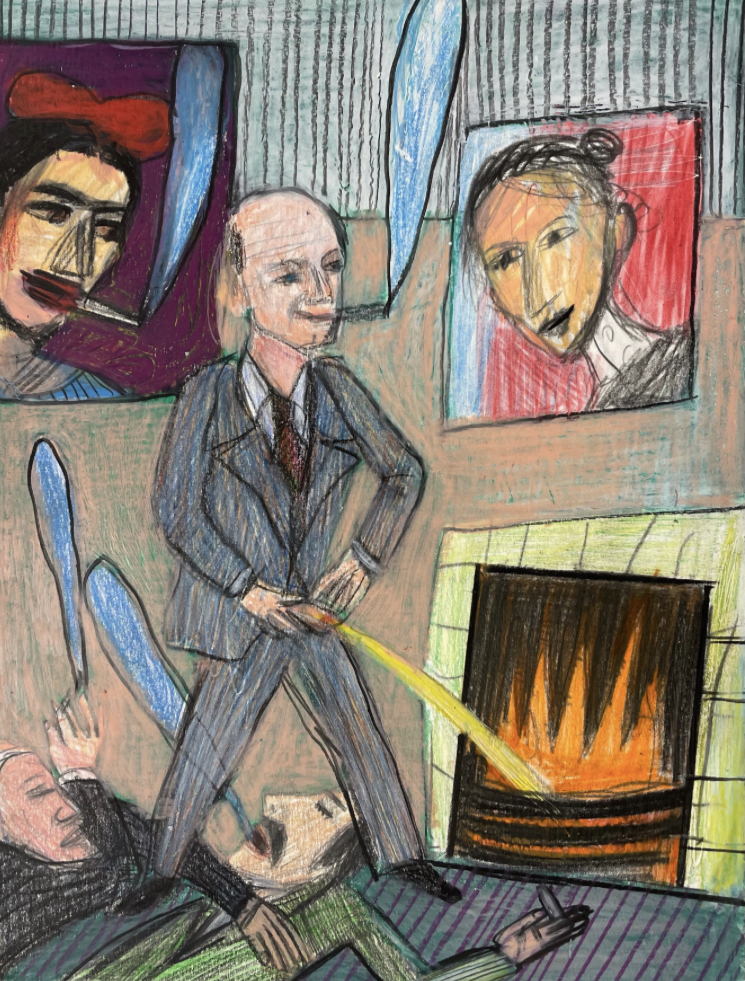

Traditionally, art history braids together the three strands of time, place, and human creative production. This is effective in creating a common base-understanding about art through the centuries. But my favorite moments of Art History 101 occurred when our professor, Rita Hammond, deviated from the outline and told us about Jackson Pollock peeing in Peggy Guggenheim’s fireplace. Another time, Rita (who was in her seventies and reminded me of Ruth Gordon in Harold and Maude) told us about the time years before when she and a friend showed up unannounced to meet Georgia O’Keeffe at O’Keefe’s New Mexico ranch. O’Keeffe tried to turn them away at the gate and Rita responded, “Then what the hell is it all for?” This worked like a kind of password because Rita and her friend spent a lovely afternoon at the ranch. This is the human side of a life in art, and I have always been drawn to and moved by it.

Art History textbooks leave out thousands or millions of these anecdotes. They also leave out (because they cannot contain) the mystery of why and how humans make art at all. Matthew Collings’ drawings include both. Collings’ art history is truly artist-centric, not at all chronological, and borderline metaphysical. The drawings are a mash-up of fact, gossip, and invention. They include artists, musicians, writers, mystics, biblical figures, political figures, the British royals, and occasionally Collings himself. They address art as a tradition, as a cult, and as a lens through which we can examine the collective conscience of society. They allude to the mystery of creativity and the interconnectedness of those who engage with art. In Collings’ version of art history, timelines get tangled and the membrane between the living and dead is permeable. Collectively, his drawings are not so much a history of art as an art séance.

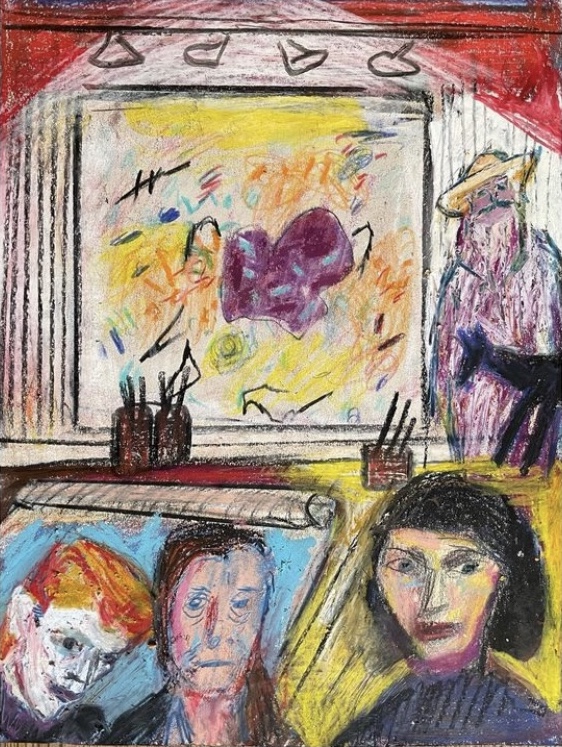

In this drawing, the same group – Bowie, Mitchell, Monet, and Bourgeois – reconvenes. The dog is absent and everyone but Louise Bourgeois is smoking a cigarette. Mitchell holds a paintbrush; the atmosphere is congenial and productive, but like most of these drawings, the figures seem to be paused in something like a trance. None of them seems bothered by their aesthetic differences (or similarities) or the fact that some of them died more recently than others; that they are, in a sense, phantoms. Every artist who has spent a long night in the studio knows that eventually, the ghosts will come.

(Come back soon for Part 2.)