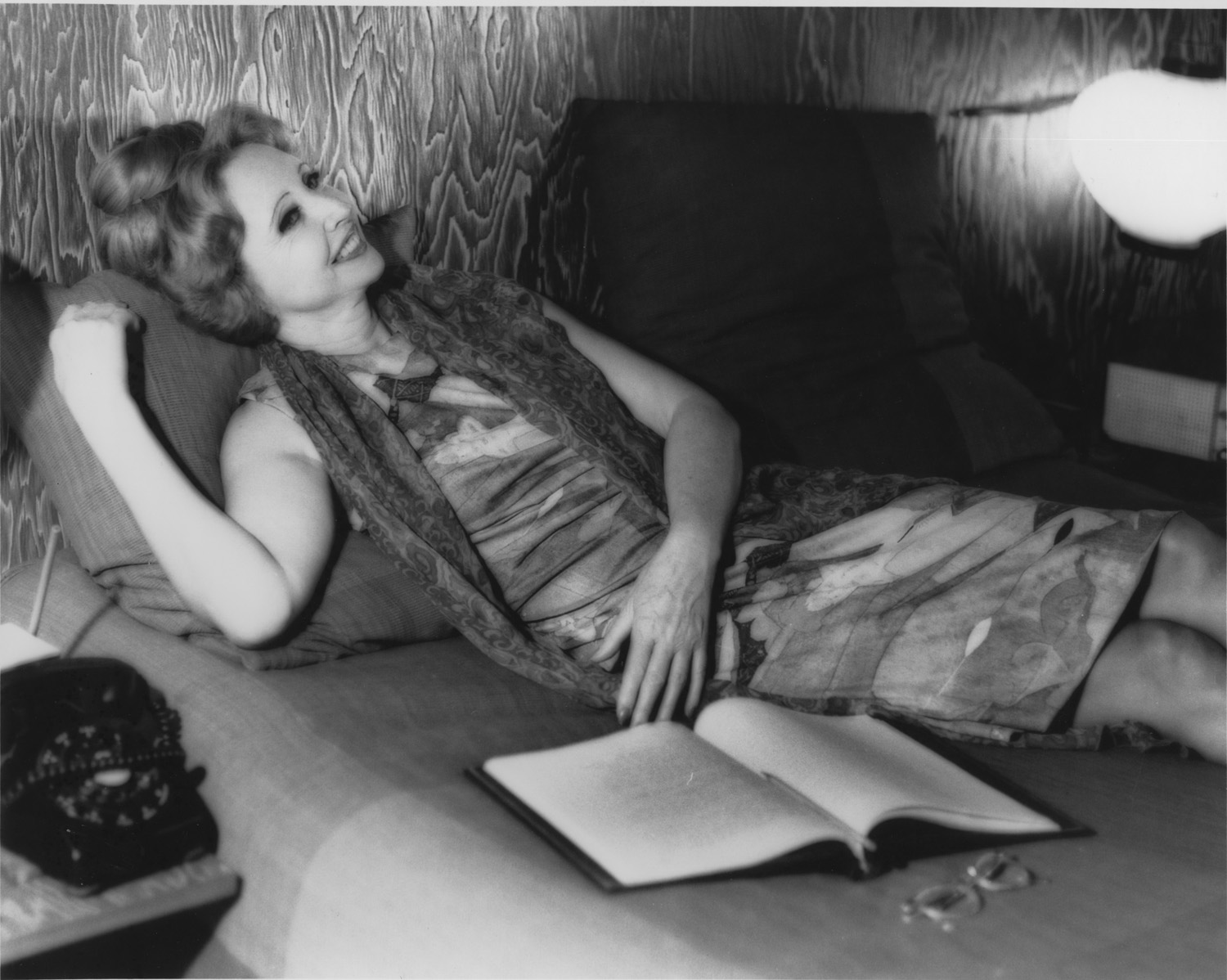

Interviewed by Jeffrey Bailey (1976)

Anaïs Nin has attained a long-delayed place of honor in contemporary letters through the impetus of her renowned diary and five-volume roman-fleuve, Cities of the Interior. Born and reared in France, of Spanish and French-Danish parentage, her lyrical insight into the human condition has touched the emotional and intellectual lives of people around the world, people who are linked to her (and to each other) by an abiding belief in the reality of imagination and the possibility of a benevolent and evolving self.

The following are excerpts from a conversation between Anaïs Nin and Jeffrey Bailey, recorded at her home in the Silver-Lake area of Los Angeles.

New Orleans Review

There is an interesting quote from Volume One of your Diary, in which you say, “I only regret that everyone wants to deprive me of the journal, which is the only steadfast friend I have, the only one that makes my life bearable, because my happiness with human beings is so precarious, my confining moods rare, and the least sign of non-interest is enough to silence me. In the journal, I am at ease.” I think you were referring to Henry Miller and to certain other friends who didn’t understand your obsession with the diary. You also say, “This diary is my kief, hashish, and opium pipe. This is my drug and my vice. Instead of writing a novel, I lie back with this book and a pen, and dream . . . I must relive my life in the dream. The dream is my only life.” How much of a conflict was there for you in expanding from the privacy of the diary into the novels which, unlike the diary, were meant for immediate public consumption?

Anaïs Nin

At one moment, it seemed like a conflict. The feeling that Henry Miller had and that Otto Rank had was that the diary was a refuge and a shell, an oyster shell, and that I was going inward instead of coming out to face the world with my fiction, since I concentrated on writing something which couldn’t be shown to people. The conflict doesn’t exist for me anymore. I see them as being interrelated, the novels and the diary. I see that the fiction helped me to write better for the diary; it helped me to develop the diary in a more interesting way, to approach it more vibrantly than one sometimes does when you’re simply making a portrait or communicating a whole series of events. I feel now that they were really nourishing each other. At one time, I seemed to be trapped in the sense that I couldn’t do the outside writing; I was more comfortable not facing the world, not publishing, not facing criticism; I was hypersensitive about those things. I was more willing to incite others to write.

NOR

Was it intuition that attracted you to your famous friendship with Henry Miller?

Nin

Yes, it really was. Intuition, and the fact that Henry had, and has, a great presence, a sense of himself that is quite overpowering. Essentially, I just enjoyed his company and although his work and his style differed a good deal from mine, I respected his efforts and admired his goals. But I never discount the importance of intuition. It was intuition, for example, that made me recognize Antonin Artaud as the great talent he was; much more than an eccentric, a true poet and mystic.

NOR

Would you say that most of your friendships with other artists came about as a result of their exposure to your work?

Nin

Well, it works both ways, of course, but a good number of them probably did. My work made it very easy for me, and I’ll tell you exactly why; I’ll make a confession: when I was sixteen, seventeen, really up until the time I was past twenty, I was horribly shy. I didn’t talk. Henry Miller said recently that I was the best listener he’d ever had—and it’s because I simply didn’t talk. And that, of course, is partly why I went to the diary. I wasn’t open myself, but I like others to be, and they were with me. Eventually, the shyness disappeared because other people made the first gesture. That’s the wonderful privilege about being an artist, because once you’ve said something that means something to others, they come towards you and the shyness is no longer a problem. For instance, last year I was able to lecture extemporaneously in front of a large audience, which is something I never would have done when I was younger. I never could have even imagined it. Henry said he couldn’t believe it, having known me. Sometimes it doesn’t turn out so well, but you do have the feeling that you’re talking directly to the people.

NOR

What are your daily writing habits? Is maintaining a regular routine important to the accomplishment of your writing goals?

Nin

Routine and discipline—that is, writing every day, and never erasing or crossing out—have been very important. I always write in the morning, usually between 7:30 and noon, and the afternoon I devote to correspondence and miscellaneous things. I type when I work in the mornings, and only write longhand in the diary.

NOR

So much of your style reflects a belief in spontaneity and continuous “flow.” What is your attitude toward revision and re- writing?

Nin

Re-writing is a special problem because it means that something about your book is basically flawed and has to be corrected. If that’s the case, there’s no escaping it. My attitude about revision has never been enthusiastic, probably because I dislike obsessive perfectionism. I would always prefer to start another book than to concentrate on revising something I’d already done; I think when you go on to something new, you learn new things and you tend to become better. I just think that you benefit more by going forward than by backtracking.

NOR

I believe that you first began writing in English when your mother brought you as a girl to New York City. Did you keep writing in English after your return to France? How do you compare the two languages?

Nin

I wrote the diary in French from the age of eleven to about seventeen. After that, everything was in English. I think that whatever language you master, you love; you can’t avoid being involved with it in a very intense sort of way. I fell in love with English as a second language when I studied in New York public schools, and my mother was very helpful. She had learned beautiful English at a New England convent. I think you’ve got to appreciate each language for its unique qualities, its particular resonance. I thought the word “you” was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard.

NOR

We seem now to be swept by a tide of nostalgia, a series of tides, really. How do you react to this? Are you nostalgic?

Nin

No, I’m really not. I love my present life, I love the people who visit me now. I’m much more interested in experiencing new cycles than in looking back. I tend to feel negatively about nostalgia; I think we go back when we feel stunted in the present life. People who are nostalgic have known something good in the past and want to pick it up again; say, for example, the houseboat period in my own life. When I’m in Paris, I look at those boats gently tossing on the water and I recall many good things, but I really don’t have that nostalgic craving. Each cycle of my life interested me equally, but I have no desire to go back to any of them.

NOR

Your published diary begins with a beautiful description of Louveciennes. Is your house there still standing?

Nin

It’s still there, but it’s crumbling. It’s in the guidebooks and everyone who goes there sees that it’s falling down.

NOR

Does anyone live there?

Nin

People live there in summer. The French landlords are like Balzac’s miser; they don’t want to fix anything so they let it go and rent it during the summer when it doesn’t matter if the furnace isn’t working. The place is 200-years-old, you know, and when I had it I had to fix everything myself. But Louveciennes is lovely. It’s got a wonderful atmosphere, very rustic, although it’s only twenty minutes from Paris by car. The Americans built a modern village next to it for the army, but they fortunately didn’t touch the old village so that it’s just the way it was, with the church in the middle and the shops around it, a typical French village. It’s quite historic, too; Renoir lived there, although I didn’t discover that until after I had left. You know, I went back there under rather strange circumstances which should show you that I’m really not nostalgic. German television wanted to do a documentary, and we did a whole day’s work at Louveciennes and had many complications. For one thing, they wouldn’t let us into the house, but this was good in a way, because it allowed new things to happen; it forced us to create something out of the immediate present, out of what we are experiencing. It wasn’t any longer focusing upon the past.

NOR

Paris in the 1930s was the place to be. What did you think of Fitzgerald and Gertrude Stein and that group?

Nin

The younger writers thought that they were passé, too 1920s. We were trying to be our own writers, and we didn’t have much respect for Hemingway or Fitzgerald. We weren’t thinking about them so much as about ourselves. I went to Gertrude Stein’s place once and found her very tyrannical. As we know now from the biographies, she didn’t like women. She thought that they were frivolous, even stupid. She much preferred the company of men and tended to isolate the women. I felt myself that that was true. It’s very clear, from those biographies, just how poorly she regarded members of her own sex.

NOR

Did you have much contact with writers in New York in the 1940s?

Nin

In the 1940s, when I came to New York, I could have met a great many of these people; in fact, however, I only met a few. There was Richard Wright, and Theodore Dreiser, who was quite an old man then. I didn’t meet a lot of these people because I had a rather severe problem with them: they all drank so much. I liked several of those who drank: James Agee, for example, and Kerouac. They were both great talents. I remember being very keen on meeting Kerouac, but I just didn’t have that capacity for drink. So often someone would come to meet you already drunk, and I found that frustrating. I think it reflected an inner frustration on their part. I can see two people who already know each other going out and drinking together, and having a good time, but only after something has been established. It works well with some, of course. One hears, for example, about how Tennessee Williams and Carson McCullers drank and wrote together, sometimes consuming tremendous amounts and yet producing marvelous work. But this business of going off and being dead drunk is something else.

NOR

This is a common stereotype of the writer: someone who re-orders reality through his work and escapes from the outside world through drink or drugs. Do you think that having some sort of pervasive neurosis is simply part of the artistic personality?

Nin

No, I don’t think so. But I do think that, as Americans, we have a collective neurosis. My belief is that we create better without it. There are a great many romantic notions that neuroses are necessary; that pain and sorrows are necessary for the writer. I reject this as a false romanticism. We all have problems, of course, and some of them turn into neuroses, but the object is to get rid of them. As I shed mine, you see me entering into new cycles. The minute I would shed one neurosis—I had many of them—I would then be able to go on to another cycle. There was the cycle of obsession with the father, and I dropped that; and then there was the obsession with the mother, and I dropped that, which is the way it should be. We’re none of us ever just one thing, and we shouldn’t allow our growth and development to be blocked.

NOR

Your Diary is famous for its massive size as well as for its style. How do you handle the problem of editing, of deciding what to publish and what to delete?

Nin

There are several problems determining what can go into the published diary, and people are sometimes hostile about what I’ve left out. They don’t understand that you have to consider two things very carefully: one is your own ethical standard which concerns protecting the privacy of people who have confided in you, and the other deals with the publisher who demands that I receive permission before the portraits can be published. So, of course, I’m inhibited that way. The editing is really dominated by my own ethics because sometimes you can write something which doesn’t seem to be destructive but which can, in fact, be harmful. For instance, we had a charming storyteller friend in the Village days. He was an alcoholic and a homosexual; we didn’t think anything of that, and in the diary I just described his storytelling. And when I sent it to him he said, “Please! I’m working for the State Department!” Had I published the piece, I would have hurt him without intending to, which is why I’m glad about the permission requirement. I have to send these portraits to the people who are concerned, and sometimes they tell me to change something or it would have a bad effect upon them. I don’t want to be destructive.

NOR

When you send these portraits to close friends or associates and they ask you to make certain changes which you’d prefer not to make, does this cause special problems?

Nin

No, because we talk about them. For instance, with James Herlihy, he read everything I had referring to him and corrected one factual error, a date concerning his play, I think, and that was all.

NOR

A number of expatriate writers who have settled in Los Angeles have been attracted to various religious cults found here, particularly to Eastern sects. Have you ever been drawn in that direction?

Nin

No, I was never attracted to Eastern religions and I’m not attracted now, even though I have great admiration for Asian culture. Nor was I ever attracted to Eastern philosophy. I love the East, but I was trapped once, and I am determined never to be trapped again.

NOR

How was that?

Nin

In Catholicism. They say, “Once a Communist, always a Communist; once a Catholic, always a Catholic.” It’s very hard to come out of a dogma, to transcend it. Although I finally did, I’m very wary of dogma, and of any organized religion. I am religious; I can accept the metaphysical, but not the dogmatic. That’s why I didn’t have the same intimacy with writers who veered toward religion here, the closeness that I had with my friends who were primarily concerned with art. The kind of metaphysics I found here simply didn’t attract me. Of course, I know that many of the young are attracted to it.

NOR

Why do you suppose that is?

Nin

It makes for a balance in American life. It gives a space for meditation, for repose, to a way of life which doesn’t have repose. If you go to Japan and sit in a restaurant, everything is so quiet, people are taking stock of themselves. Everything is done so quietly, and there is a natural meditation. You don’t need to make an area of quietness; just having tea takes on that kind of quietness.

NOR

Can you come to some sort of “religious” realization through art?

Nin

Yes. I once read a description of satori by a Spanish author, and for the first time it was a very simple description. He said that it was a feeling of oneness with nature, a oneness with other human beings. I said, “Is that all it is? I feel that; I always have.” It’s not such a complex thing that you have to go through such a discipline.

NOR

You are known for your use of the roman-fleuve concept. It seems to me that the roman-fleuve requires a special way of looking at all the elements of good writing: character, motivation, personality, timing, construction. It really rejects the conventional idea of storytelling.

Nin

You’re quite right. I think that that comes out of a philosophy, or an attitude. My attitude was one of free association. I saw things as a chain, and felt that everything is continuous and never really ends. I had a sense of continuity and relatedness; relatedness between the past and the present and the future, between races and between the sexes, between everything. That’s an attitude that sustains me as a writer.

NOR

For a long time, American publishers resisted this conception. Why do you think that was?

Nin

I think that when you are uneasy, when you are not at one with things that you tend to lose yourself in technique. Publishers are very big on technique. The technique of the novel and the short story was that it had a beginning, a middle, and an end, and they taught you that. They taught you to make plots, to plot the novel before you wrote it. The technical part of writing became the reality, but in fact this isn’t at all true to life. The people who did this claimed to be realists and that I, supposedly, was not. Actually, I know now that I was nearer the truth than they were, because we don’t live our lives like a novel. We don’t have these convenient denouements, these neat finishes; it just isn’t so. Life goes on and on in circles; perhaps the past will tie up the future for you, but who knows? One can only guess.

NOR

Do you think that the roman-fleuve concept will affect the future development of the American novel? Will we grow further away from the ideas of definitive plot and tight construction?

Nin

Yes, I think so, but for the moment I can’t really tell; for the moment, there is this great interest in diary writing. But then, American society is set in such a way that this interest in the diary is quite natural; it tends to reassure people about their own individuality.

It’s important to let your imagination go, especially at a young age. I let mine run free when I was young. I loved to make a drama out of everything, even the weather, and I allowed this to come through in the diary. If you do see things through the eyes of imagination, you should relate it. Obviously, as far as the dramatization of experience or feelings is concerned, I was doing that when I was eighteen. Very little happened to me at that age; I blew it up and let myself go. Maybe I did that because I considered it a work that no one would see and I therefore felt free. And I have everything in there: quotations from other writers, notes on things that I hoped to do someday, ideas for stories. The storytelling element in a diary is good; it’s what distinguishes it from a boring journal. A number of women send me their diaries, and many of these diaries aren’t interesting because of the way they are told. But it‘s only the way they’re telling it that’s not interesting; the things themselves are always interesting. They don’t know how to bring it out, mostly because the imagination is stifled.

NOR

Does it ever bother you when critics say, or insinuate, that your diaries are more fiction than fact?

Nin

No, that doesn’t bother me. After all, I know the facts, and I know that the facts are true. I also know that I see events in a lyrical or dramatic way and I feel that this is valid. I know that the way I see Bali, for example, is not the way the travel writer for the L.A. Times sees Bali; he will write about the hotel prices, and the shops, and all that, which is important. But my point of view is valid, too.

NOR

How do you react to the criticism—which is voiced by people who apparently have had only a cursory exposure to your work—that you are self-obsessed; they seem fond of using the term “narcissistic”?

Nin

I try to laugh that sort of thing away, because I think they are terribly wrong. I think the reason we have felt burdened or constricted in America, why we have felt so alienated, is that we didn’t have any Self, we didn’t have an “I.” The cultural atmosphere of France did affect me in the sense that all the writers there kept diaries, and you knew it was Gide, and you knew it was Mauriac; they were entities. That’s where I got my tradition, and there is no diary without an “I.” So I laugh at this criticism because I think it comes from Puritanism. I think it comes from the Puritan conception that looking inward is neurotic, that subjectivity is neurotic, that writing about yourself is immodest. I think it’s terribly funny. Every now and then the narcissism charge comes up; they apparently don’t know what it means. One French woman said, “If that’s narcissism, it’s a pretty exigent one. She’s demanding an awful lot of herself.” Quite obviously, to anyone who is very sensitive, the diary reflects a lack of confidence, a lack of certainty about myself, and the reason why I wrote down the compliments was because I needed to.

Anyone who can read through a psychological character knows that I wasn’t very pleased with myself. I was always in a struggle to achieve more in my own character. I was always involved in a confrontation with myself, which is painful. I think that’s our heritage from Puritanism. It’s a lack of self-understanding. Most people have an illusion about their being objective. They feel that by not talking about themselves, they are doing an honorable or virtuous thing. Again, this is from Puritanism. And I must tell you this, because I think it’s interesting: the women, the ones who really went into the diary, took it very differently. They said just the opposite, that this was not my diary, but theirs. They bypassed this business of narcissism and the “I” and said, “that ‘I’ is me.” What they wrote to me was, “I feel that way about the father. Your father was not quite like mine, but I felt the same way.” They wrote that about many things, that they felt the same. My feeling was not that I was at all a special being, or an eccentric, but I was voicing things for other women, and for some men, too, because there are men who understand the diary very well. It’s a falsity to say that because you have a sense of yourself it means that you are also speaking for others, but the result of the diary, for those who are really into it, is that they feel that I have helped make them aware of who they are, and where they are going, and how they want to get there.

NOR

And this couldn’t have been an intentional effort on your part?

Nin

No. I thought I was telling my own story, and that I was exposing my neuroses so that I could be rid of them. Simply telling the story was more important to me than any other consideration. I needed to tell it.

NOR

I’d like to turn to the question of the persona, which is a subject that you’ve pursued in both the fiction and the diaries. Would it be accurate to describe the persona as a necessary but transitory state, a condition which we should try to outgrow?

Nin

I think that the persona is something we create defensively. It’s what we present to the world, what we think the world will accept. We all do this to a certain extent, but I don’t think that we can ever really communicate on the basis of persona to persona. Thus, we become lonely within the persona. I experienced a great deal of this loneliness in the early diary, when I was playing roles, pretending to be a wife, pretending to be this or that, but never fully bringing myself into anything. Only in the diary did I really exist; only in the diary could I open myself to others. When you realize something like that, you become angry at the persona because it’s keeping you from contact with others. If I sit here trying to create a persona for you, everything would be ruined. And only when you outgrow that compulsion to conform to a mere image—and I think you do outgrow it, as one truly matures—it’s what Jung called the “second birth”—will you really dare to be yourself and to speak out about your own experiences. In the beginning, I couldn’t do that face to face with people; I could only do it through the diary. There again, you see that I was really a scared person. But I was willing to go back to the diary when I saw that it could help me destroy the persona.

NOR

Then, in a healthy person, the persona always dissipates entirely?

Nin

I think it’s one of our goals that it should dissipate because it’s a defensive thing, it can imprison you. We’ve all known personalities—celebrities—who are imprisoned by their own public patterns. With me, recognition came too late for me to be caught by the public image. I was already mature and rid of my persona, and I wasn’t going to take up one for the lectures or TV. Fame came so late that I could really be myself, on TV or anywhere else. I wasn’t constrained by all these things which create artificiality. But if it had happened to me at twenty, I don’t know if I could have done it.

NOR

I was wondering about the female characters—Lillian, Djuna, and Sabina—who appear in Cities of the Interior. Oliver Evans described them as “archetypes,” and I wondered how valid you felt that description was. Also, to what extent would you say these women were conscious extensions of your own personality?

Nin

I wouldn’t say that they are archetypes, except in the very broad sense that each of us is an archetype of our predominant character traits. I certainly didn’t conceive of them in a rigid way that would make them literary archetypes. As far as their being conscious extensions of my own personality, I wouldn’t say that at all. One can argue, of course, that every character comes out of an author’s perception, and that since perception is a major part of a writer’s psyche—of his personality if you prefer—it may be said that fictional characters are therefore, in some way, representative of the author. But that argument is a bit convoluted.

NOR

We talked before about the mutual affinity which seems to exist among many artists. Is there also an inherent antagonism?

Nin

Oh, yes, I suppose. But that’s from envy and jealousy, don’t you think? In France, it was less so because the stakes were not material, the writers didn’t really make any money. There was none of that rivalry that I found when I came to this country where there was a great deal of envy and jealousy. Here, there is a struggle for material status among writers. I found that they were not as collective, or communal, or fraternal, not as willing to help each other, as we were. But then, we didn’t have the temptation. We weren’t expecting to make $20,000, or anything like that, so I’m aware that not having these temptations made being fraternal much easier. The American experience, to me, became obviously tied up with commercialism, with making rivalries and competitions. In France, the young writers didn’t think they were going to make it; that’s the truth. I can remember going with Henry Miller to the Balzac Museum and he said to me jokingly, “Do you think our manuscripts will ever be shown this way?” We really didn’t think they would be. We weren’t aiming at that. So it was easy enough to be fraternal and devoted, whereas the American has a terrible financial temptation.

NOR

We’ve all heard stories about famous writers who were once friends but who have come to a parting of the ways. As an extension of these rather personal antagonisms which arise between individuals, have you ever seen Man, the social entity, as being a natural antagonist, either to women as a group, or to you personally?

Nin

Oh, yes. I think we have all suffered from that. We don’t know the origins, but I certainly think that there are wars between men and women. I think that certain active Feminists are currently trying to make a war.

NOR

Is it a justified war?

Nin

No, I don’t believe in war, in any kind of war. War isn’t going to solve the problems of our relationships, or affect our psychological independence, or our freedom to act, or our standard of living.

NOR

Historically—and psychologically, I suppose—the sexes have tended to circumvent each other, and have thereby thwarted understanding and mutual acceptance. Much of this is due to role- playing. Do you see this as inevitable? Is it bound to continue?

Nin

No, I don’t think so. I think it only happens when something’s gone wrong. We all have causes for hostility which aren’t necessarily related to sexual matters—we all get injured or get betrayed—but in proportion to how we can transcend those things, we become a different sort of human being. I didn’t have any bitter feelings, for instance, after being ignored for twenty years, when the same publishers who turned me down began sending me books to comment on. I don’t feel bitter about that; it’s something I understand. But some people accumulate bitterness or hostility, mostly when they blame others for where they are. I think women tend to blame men for where they are when they should be spending at least an equal amount of energy looking inward to see how they got there.

NOR

One can’t argue very much with the economic points made by the Liberation Movement, but somehow I feel that many women underestimate the more pervasive psychological power or influence which they have always had, and I don’t mean merely the sexual power over men. It’s something more nebulous than that.

Nin

That’s the kind of power women had in Europe, but women here never seemed to have that power; it’s really a kind of spiritual power. Somehow the Frenchman considers the woman’s opinion rather automatically when making decisions. The Frenchwoman

may not have had many legal rights or the power to earn a living, but she did have this other power. She was not simply a sexual object; she had an influence. But I think that the whole thing will mellow, it’s mellowing already. You know, Americans essentially love to foster hostility. They encourage it; they love to fight. The media encourage it also. They don’t encourage reconciliation, and understanding, and compassion. They never try to reconcile, they love the hostilities and the prize fights. That’s one thing I find much less in Europe. Perhaps they’ve already worked out their aggressions through the wars, I don’t know.

NOR

Of the younger women writers being noticed today—Joyce Carol Oates, Erica Jong, Susan Sontag, Germaine Greer, the late Sylvia Plath—are there any about whom you’re very enthusiastic? Also, when you were beginning your career, were there any writers to whom you looked for guidance or inspiration?

Nin

My inspiration writers were always Lawrence and Proust. About the younger writers, I’m afraid I’m not very enthusiastic, although I do very much admire Germaine Greer. I think her efforts have been very worthwhile.

NOR

Many people feel that the official recognition that you are now enjoying is long overdue. How do you react to this sort of “establishment” approval?

Nin

I react in different ways. My first impulse is to back away from organizations and official honors; but I’m also aware that recognition has an important psychological impact which affects a number of people, not just the person being recognized or honored. I’m often reminded of that by my young women friends, whom I call my “spiritual daughters.” They remind me that being given a public forum also gives one an opportunity to exert a positive and constructive influence.

NOR

After your long involvement in the composition of your continuous novel, Cities of the Interior, Collages seemed to mark a new phase in your approach to fiction. Do you have plans for anything similar?

Nin

Collages was a flight, really. I was so disillusioned by the reception of the novels, it seemed like I had reached a dead-end. And then I suddenly began to think that maybe my major work was the diary. So now, of course, I’m involved in finishing Volume 7. When I do finish it, I plan to go through some of the childhood diaries; then, who knows? But I had the feeling that fiction, for me, was disastrous. Even though now people write quite beautifully about it and seem to understand the fiction, somehow I have become detached from it.

NOR

It’s hard to imagine that you could feel that way.

Nin

It could just be because the fiction led me to a wall. It led me to a sort of troubled silence, and it could be that that influenced me. But it could also be that I realized I had put much more into the diaries. And, as I said before, there are imaginative elements in the diaries, too.

NOR

On the whole, would you say that your life as an artist has been as rewarding as you could have wished it to be?

Nin

Definitely, yes. There is a special kind of reward which is wonderful, and it’s something which, I think, only artists enjoy. It has nothing to do with material rewards. It’s the reward of finding your people, the chance to make a world, a population of your own, and that’s wonderful because you find yourself as a connecting link between people who think as you do and feel as you do. And suddenly you’re not alone; there is a constant exchange which you enjoy yourself and which you help to promote among others.

NOR

Are you optimistic about what you see happening around us all today?

Nin

I’m optimistic only about the new consciousness of the young, that’s all. I’m not optimistic about the country or about the tyranny of business all over the world. Now it’s too late for revolution. We couldn’t make revolution against the corporate establishment no matter how much we wanted to because it’s simply too big. But I am optimistic about people’s ability to develop themselves in a more meaningful and more lasting way than we’ve experienced in the past. I believe that the change of consciousness will have an impact for the good.