Bert Drieghe works four days a week as an electrician near Ghent. In our email exchange in English (Bert’s native language is Flemish) he specified, “I don’t do house installation, but make electrical cabinets for industry, such as conveyor belts, mixers, rollers, automation… Just like everything in my life, this certainly has an influence on my paintings.”

Bert paints every day. His studio is in his living room, which he shares with his girlfriend and daughter, “hence the small sizes,” he said, also pointing out that he mostly paints on found material.

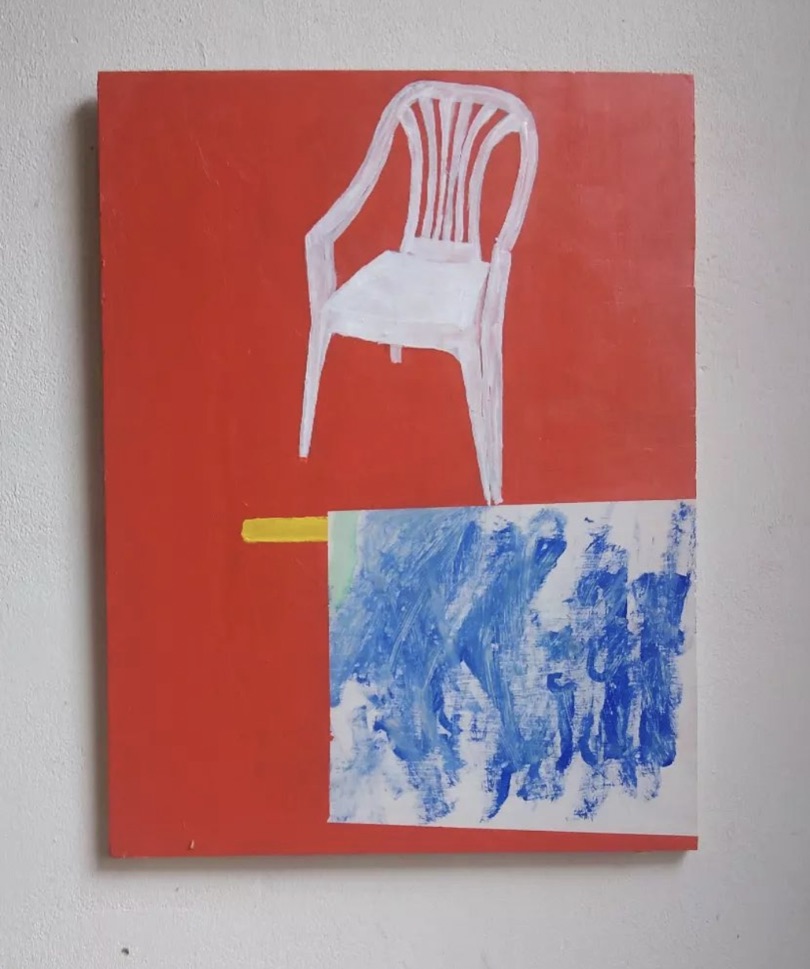

In October, I met Bert on a video call and toured his exhibition, Doorzichtig (See-Through) in Ghent at Sylvester Gallery run by Vincent Laute. The ceiling was painted a vivid green, the same green that appears in some of Bert’s paintings. The refracted color could be a nightmare for some artists, but in this case, it seemed to contain the atmosphere of a cohesive world beneath it. The paintings and painted wall-hung sculptures interacted with the space and each other. Small groupings of paintings read like a chapter in a book or a strophe in a poem. Bert told me that in the past, galleries have asked to show his abstract work or his figurative work, rather than allowing the two to co-exist. In his work as a whole and in several singular works, abstraction and figuration coexist; this seems an essential part of the artist’s voice.

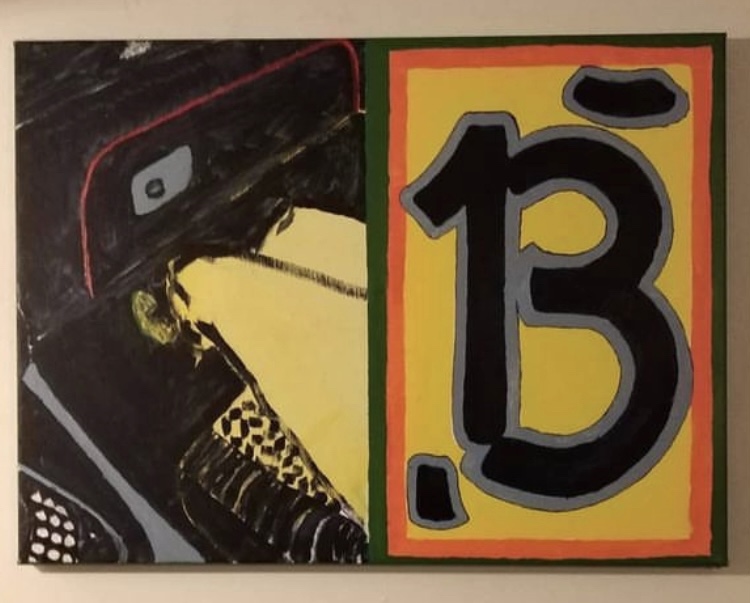

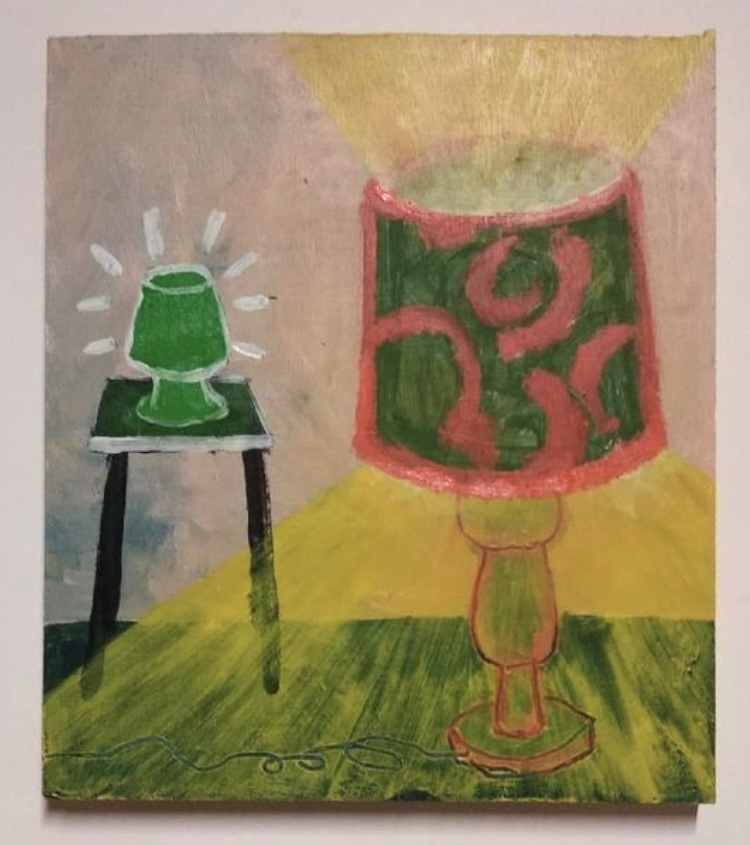

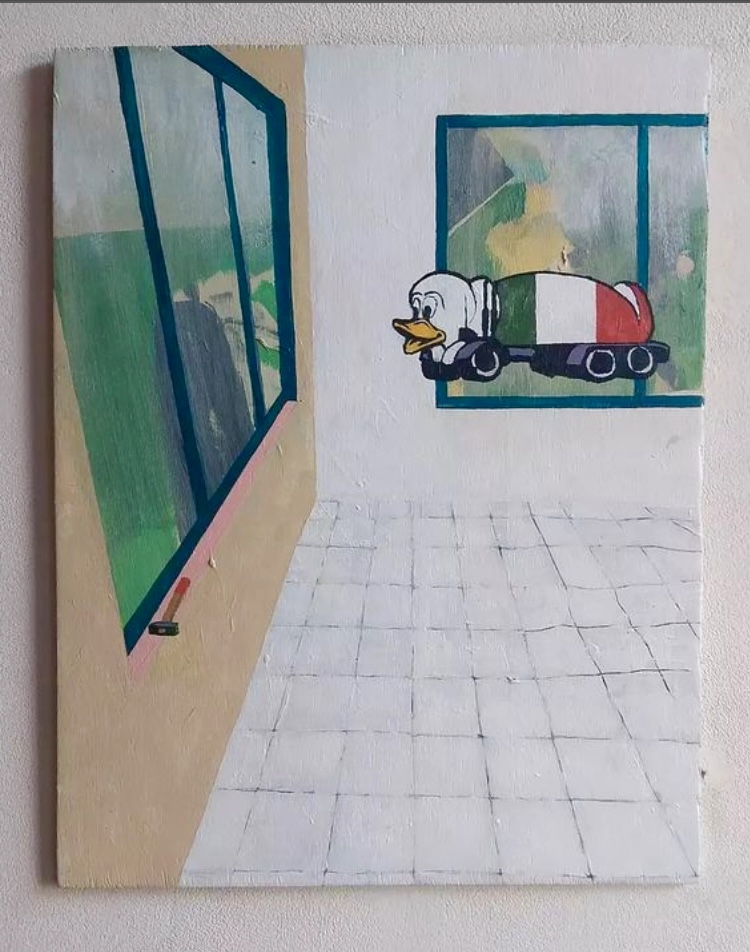

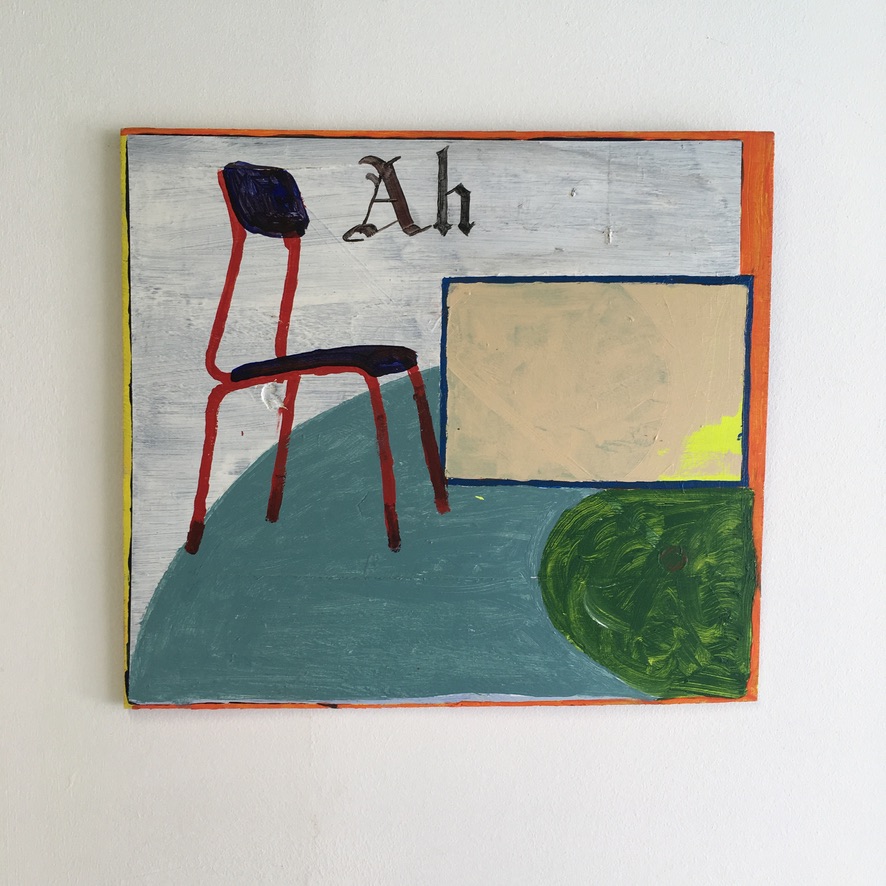

I would know one of Bert Drieghe’s paintings in a pile of a hundred, and yet each of his paintings is distinct from the others. For a while this puzzled me, as I tried to identify the common denominators. The scale is always small to modest. The palette is consistently vivid, less a painter’s palette than that of plastic objects. The surfaces are determined not only by actions and accidents of paint, but by the fact that the support is often ruddy or irregular, scavenged material. Many paintings include figures, quotidian objects, and abstract forms rendered in flat color. There are also animals, words, and a minimally articulated illusion of landscape or interior.

I hesitate to call what is depicted in Bert Drieghe’s work the subject. My sense is that the true subject exists between the objects or forms, in the sum of them, the subject itself more ethereal, elusive. The artist’s distinct voice floats in the negative space or is wedged between the objects in the paintings. The true subject of this work seems to be the mind of the artist, a mind in a life, trying to make sense of it. In a day of life, we encounter a mash-up of tangible and intangible objects, some clearly perceived, others seen in the periphery, abstracted. A painter, Bert processes all of this in paint. He wrote:

“As always, my life, what I see feel, think…Is my inspiration…Like any sensible person, the world makes me sick, and it’s a pity that history keeps repeating itself… I ask myself a lot of questions about that, but I have to be careful not to go crazy…I may sound gloomy here, but I’m not. I enjoy art, people, life in all its forms. This all probably comes across as very chaotic but that’s how my head works.”

Another word for “style” in art could be “voice’” a singular uniqueness, as inevitable and inimitable as DNA. Well-sponsored art students often feverishly seek what we call style. In a formal setting, style can be found through imitation, experimentation, feedback. Bert seems to have found his in secular life. Style is the surfacing of a person’s individuality, their Whitmanesque song of self. What I recognize in all of Bert Drieghe’s various work is his style, his uniqueness, the sum of his history, his materials, his living room workspace, and the things in his mind at night after a day of work, after being a person in the world.