The thesis of the new exhibition at NOMA, Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club, is ambitious. It draws a wide circle around the American artist in Nigeria, a literary journal called Black Orpheus, and the Mbari Club, a collective of artists, musicians, and writers that formed in 1961. The scope of the exhibition continues beyond Nigeria, beyond Africa, and concludes with a selection of African-American artists working in Africa in the mid 20th century. Last week, I attended a tour given by Ndubuisi Ezeluomba, exhibition co-curator and curator of African Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. It will take me more than one visit to absorb all the ideas that informed the exhibition. Within the hour I hit idea overload, so I returned to the artwork. Whenever a collection or exhibit offers more than I can take in in a certain period of time, I look around the gallery and approach whichever piece solicits my attention. Then, I stay there a while. Often, I am drawn to what is most familiar; sometimes I urge myself to look closely at something I might intuitively pass by.

A small landscape painting by Gwendolyn Knight was the first artwork that attracted me. I noticed it as soon I entered the exhibition. Knight, who married Jacob Lawrence in 1941, painted this scene of her native Barbados from memory. There is a mix of painterly edges and hard shapes within the frame, creating a low-level tension. Black palm trees suture the lower and upper halves of the composition. Geometric red roofs and identically-colored red boats on the beach are consistent with the hard-edged, summarized forms that dominate the show. But the salmon-colored sunset, blue horizon, and a road that disappears behind a far cliff, pull me into the illusion of space. of the over 125 works in the show, this painting offers one of the few illusions of spatial depth. It the only landscape.

This painting, like Knight herself, captures a clash of styles and identities: both New Yorker and daughter of the West Indies, artist and artist’s wife. What does it mean, I wondered, that my favorite work in the show is an outlier? I am a painter, so it shouldn’t surprise me that I favored the most “painterly” artwork. Every viewer comes to an exhibition or single artwork preloaded with who and what they are. Yet, it would be a mistake to miss the chance to expand, to learn, and to experience something new.

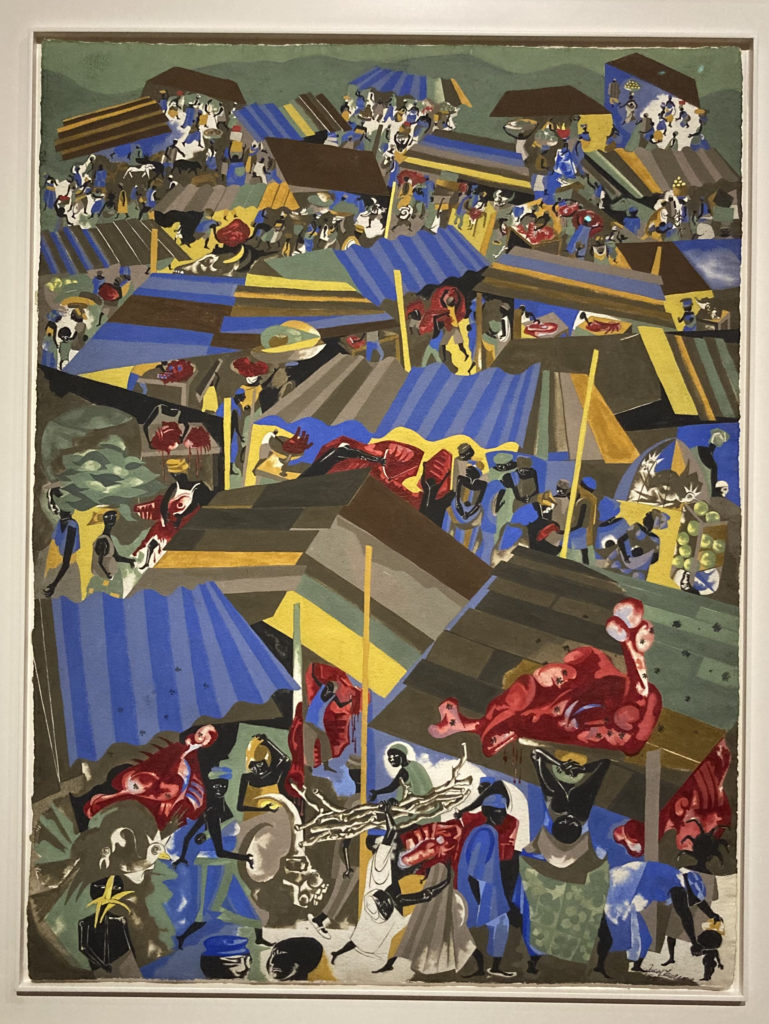

Jacob Lawrence’s Nigeria Series, the centerpiece of the exhibition, is shown in its entirety for the first time in fifty years. Several of the works in this series are street or market scenes, dense compositions of mostly black, but also red, or green-skinned figures. There are geometric forms and patterns representing merchandise and structures. When speaking about this work, Ndubuisi Ezeluomba described the marketplace as a social place of meeting, a lively and “joyful”atmosphere. Looking at crowded compositions, I felt not so much joy as overwhelm, exactly what I experience in actual noisy, crowded spaces. The exhibition catalogue quotes a letter from Lawrence to a friend describing the markets as “Visually the most exciting experiences.” This is evident in the work.

In a piece titled Street Scene, I studied the funny round heads of two babies, carried on their mothers’ backs. I wondered why Lawrence depicted these children as slightly monstrous looking creatures. One of the babies bares a full set of teeth. I wondered about the light blue oval, over (or on?) the head of the central figure. In the blue oval, there are three small figures looking somewhat tormented or maybe tormenting. Could they be spirits? Memories? When I encounter unfamiliar art (I have seen the work of Jacob Lawrence before but only in the tame context of reproduction) I shift my posture between open reception and inquiry. Questions, I think, are the key to handling the discomfort of encountering the unfamiliar.

Before I left Street Scene, I noticed how one of the baby’s hands echoed the shape of the mother’s. Despite the strange (and strangely toothy) face of the baby on the mother’s back, this was a sweet moment in the pience. The adjacent painting, Meat Market, reinforced my sense that one viewer’s joy was another’s anxiety. The splashes of red and bone shapes that repeat and diminish in size as the space deepens, made me almost nauseous. Where Knight’s painting described the illusion of depth with decreasing contrast and blue atmosphere, Lawrence did so with form and scale.

Speaking of form, the exhibition is full of geometric figures, faces, and objects rendered in flat shapes. The exhibition catalogue describes how Lawrence’s “signature style of flattened bodies” was derived from cubism, which he had studied in America. Interstingly, cubism was heavily influenced by African masks, which Picasso collected and copied.

Also present with me, as with any viewer in the exhibition, was my own history. There was something familiar about the formal elements that connected most of the work in the show. My grandfather, the son of an Italian immigrant and an Irish immigrant, opened a store called Erie Imports in Syracuse New York. The store carried textiles, bamboo and wicker furniture, jewelry, and art or at least decorative objects based on art. The import store was a source for objects of African and Asian origin at a time when most goods used by Americans were made in America.

In my grandfather’s store, which was eventually passed on my father, one ubiquitous motif was that of the flattened figure. The African-cubist-kitsch aesthetic appeared, often diluted, in prints, textiles, pottery and statues. I remember the smell of the store, a mixture of wood, spice and perfume, smells from places my father would never travel. My father’s store closed in the 1980s, when I was still very young, and shortly after Pier One, offering “exotic” products in a more contemporary setting, opened a store in front of my father’s.

Meanwhile, the home I shared with my parents and six siblings was not decorated with imported objects from my father’s store. Our walls were covered with (surprise, surprise) landscape paintings, unpeopled, the illusion of atmospheric distance being one of my first wonders of the world. I did not spend much time in my grandfather and father’s store; the scant memories I have are potent and left their impression on me.

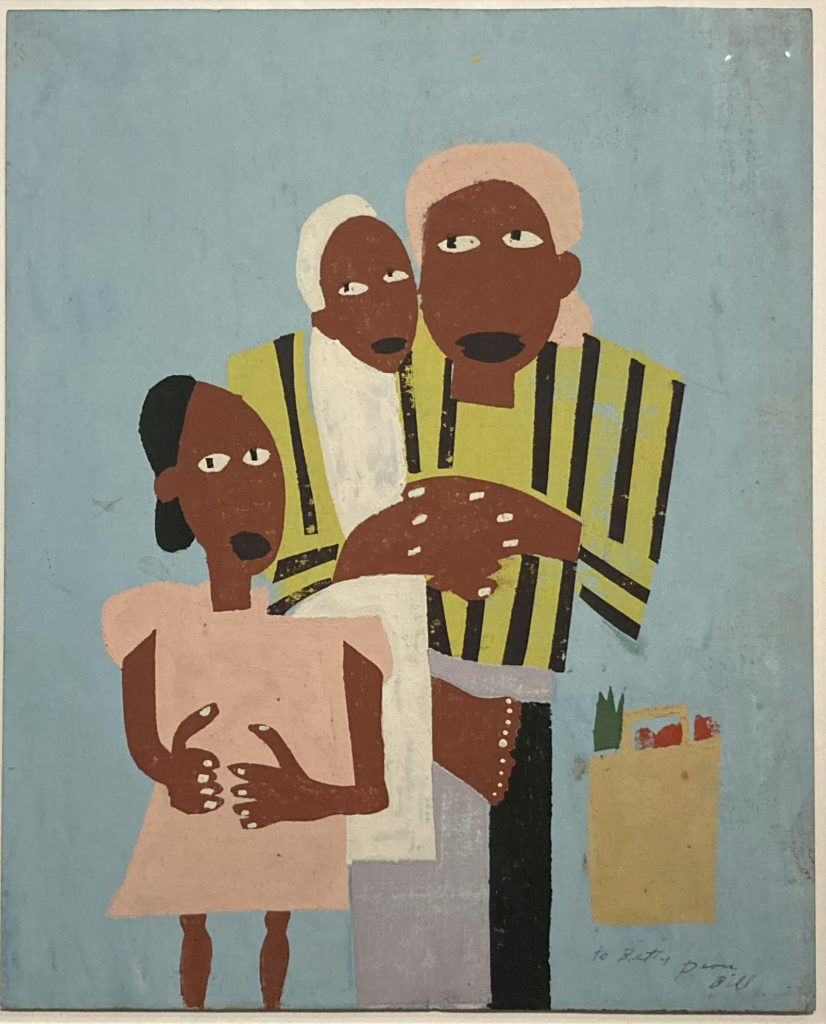

Everyone comes to an exhibition with their own history their own identity, and from their own culture. A show whose focal point is the artwork of an African-American working in post-colonial Africa, during Black History Month will invite all visitors to consider their relationship to these works, their makers, and the ideas set forth in the show. Some connections will be personal, others cultural, and some, art historical. In the last gallery of the exhibition was a painting by William H. Johnson that reminded me of the work of contemporary artist Laylah Ali. It’s thrilling to see these connections.

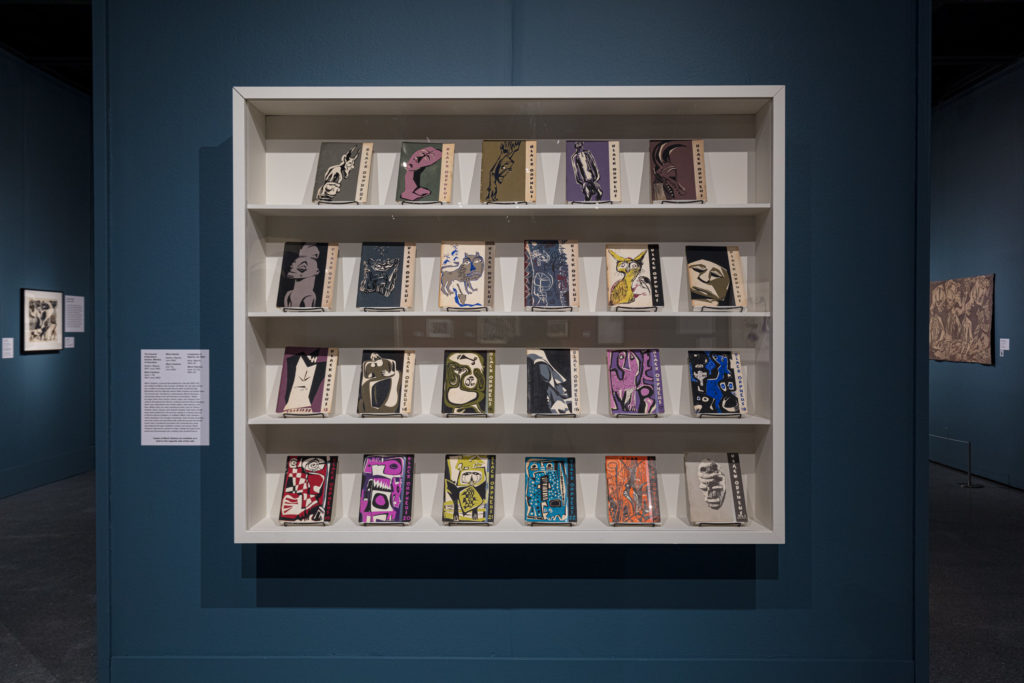

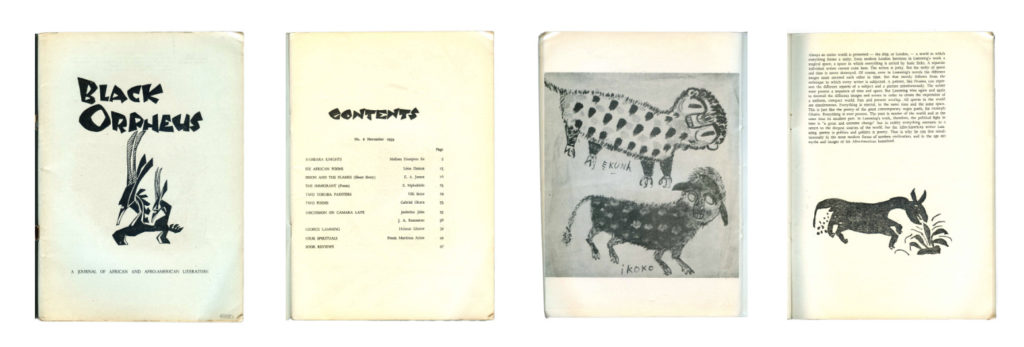

In the center of the exhibition is a display case with copies of Black Orpheus. The literary journal was started in 1957 by Ullie Beier, a German expatriate in Nigeria, an editor and scholar. The journal played a significant role in the careers of many artists and writers working in Nigeria and beyond. Its pages, like the Mbari Club, provided a meeting place for diverse talent and a way of sharing it globally. This aspect of the exhibition also hit a personal note as I am at this moment writing about art in a literary journal. History shows us again and again the incredible exchange that can result when artists of different disciplines, music, art, and literature, intersect and share a space. Black Orpheus, the exhibition catalogue explains, “enabled readers to participate in events unfolding on the continent.” On the other side of a dividing wall visitors can sit and look through copies of Black Orpheus and read the exhibition catalogue. Individual paintings and objects tell stories within their frames and forms. This exhibition is not one story but hundreds of them. By the way, in the space of the exhibition, there is a reading space with couches, catalogues and copies of Black Orpheus to look through. It’s Carnival in New Orleans. I can think of no better place in town to hide from the madding crowd.