ROOM 220 will host Anya Groner and novelist Brendan Jones on Thursday, September 15, at 7 p.m. at Antenna Gallery (3718 St. Claude Avenue). Jones will also be leading a writing workshop at Antenna from 10 a.m. – 3 p.m. on Saturday, September 17, which will involve lots of writing prompts, feedback, and an exploration of the process of putting together a cohesive manuscript. Visit here to register for the workshop!

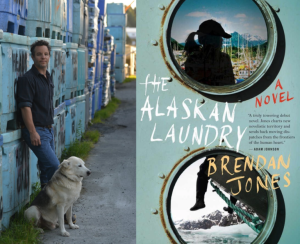

Thursday, Jones will read from The Alaskan Laundry (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). The novel draws on Jones’ real-life experience living and working on an Alaskan tugboat to tell the tale of Tara Marconi, a Philadelphia woman who runs away from the depression and anger that have taken over her life. Room 220 had the pleasure of speaking with him about his novel, writing about place, and the challenges of writing about an experience so close to his own via a female protagonist. This interview was conducted via email on Sunday, September 11, 2016.

Room 220: Can you talk a little about how you began writing The Alaskan Laundry and how the book found its final shape?

Brendan Isaac Jones: If you had told me I was going to write a novel with a female protagonist in 2005, when I began this book, I would have laughed. Jacob Sharpe was my hard-bitten, thinly-veiled Jake Barnesian male protagonist, who went out into the woods of Alaska and got lost. I had nine other protagonists, and I wrote 30,000 words for each. Tara, for her part, was initially a character named June who housesat for an anthropology professor at University of Michigan, watching over his pet rabbits. Weird, right? Very minor in the pantheon of the ten original folks I incorporated into my multiple POV calamity of a manuscript. It was only through many revisions that she evolved into Tara. I dated a Marconi in Alaska and loved the last name. It also fit with my Italian-Catholic South Philly protagonist – who only became so after many revisions.

The only way I can describe the process of coming to Tara was these 10 characters entering into a war of attrition, one character eclipsing another. For example, there was a Cuban guy named Santo; when I got my agent, he suggested the book should be a love story between Tara and Santo. Then when Jenna (my editor at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) bought the book, she thought Tara should take center stage. And so she did.

As far as how the book took its final shape, it was only through many, many iterations, and much editing. For example, there wasn’t a dog in the book until two weeks before the book was due because the publisher wanted a dog on the cover. And so forth.

Rm220: What challenges did you face when writing a character who shared many aspects of your past?

My personal experience writing a novel is that when you write and rewrite so many times you stop keeping track of how many things you change or make the same. They just evolve. Yes – we certainly share a number of similarities, but I never put too much thought (while writing) into how we were alike or different.

Rm220: Were there any struggles you faced when writing from the third person limited point of view with a female protagonist?

BIJ: It’s always a struggle no matter the POV. But if you’re speaking in particular about the female protagonist, yes, I was always conscious while writing that I would be under scrutiny as a male writing from a female POV. That said, I do believe the idea that literature is the supreme means of renewing one’s sensuous and emotional life and learning a new awareness. I certainly learned a new awareness writing Tara. On the flip side of that, you’ll notice there are no sex scenes. I was told in the Stegner workshop that I wasn’t very good at writing sex from a female POV. So there you go.

Rm220: It seems as though you’ve been publishing more nonfiction and journalistic pieces since the book release. What has led you toward these genres? What else are you currently working on?

BIJ: Good observation. Yes, both my parent were journalists (they met on the Rocky Mountain News in Denver). I’m probably most comfortable writing pieces for the Times or Smithsonian. That said, I’m about halfway through a second novel and enjoying the process.

Rm220: This may not make a great interview question, but I’m curious – The relatively short chapters of the novel left me thinking of James Salter’s Solo Faces. I remember holding my breath as I raced through each chapter of that novella. How did you settle on the structure of the novel?

BIJ: Oh god, I love James Salter. And Solo Faces. A novel before this one I wrote transferring A Sport and a Pastime to Alaska. So perhaps some of this rubbed off. As I wrote, I never intentionally decided to keep things short. It just evolved that way – and as for the 100 chapters it was originally 96, and I fooled with things to make it a hundred.

Rm220: The setting of the novel at times feels like its own character that we come to know more and more as the book proceeds, with its codes of conduct, strange personalities, and the particular terminology of commercial fishing. While it’s completely different, I know, I kept thinking of the penchant Southern writers have for weaving really similar things (less the commercial fishing, but we have a certain way of talking that’s all our own) into their writings. Did you face any challenges when characterizing Alaska? Were you at all worried about rendering the setting truthfully?

BIJ: Interesting and complicated question. It gets into why I changed the name of Sitka to Port Anna.

Each country (each state, even) has similar wild lands where the imagination plays strongest. Bretagne in France, Galicia in Spain, Scotland in Great Britain, Siberia in Russia, Inner Mongolia, and so forth. So this novel could have been set elsewhere, with different characters – but it couldn’t have been elsewhere in the United States, if that makes any sense. For example, if the novel played out in Montana, I couldn’t have taken advantage of that same end-of-the-lineness one discovers in Alaska.

Southern writers, I believe, share a similar sentiment that it could only happen here. These people could only exist here.

I was worried about rendering Alaska. I got blowback from the Native community for using native myths. I got blowback from friends and locals for naming subsistence spots. I ended up asking permission to use myth and changing the names of subsistence spots. It was a process to get it right. And of course, changing the name from Sitka to Port Anna opens all sorts of imaginative space; suddenly you’re not bound by reality.

Rm220: Do you feel any pressure as a sort of literary ambassador for Alaska, especially given that you’re a non-native? As a non-native New Orleanian, I still feel an acute awareness in choosing scenic details and writing characters when I set a story here.

BIJ: Alaska represents both end of the line, and land of new beginnings. It is a gateway that some don’t quite step all the way through. A place that tests you. People don’t care much where you come from, your history. What matters is the work you do and how you integrate into the community. It’s still a frontier with a frontier mentality. So this acute awareness and apprehension just isn’t a factor in the same way it might be in New Orleans. Of course, there’s the native population in Alaska and tension surrounding the sad history of how the state Alaska was colonized. But for the moment, it continues to be a place where people come to prove themselves, to make their story. You come to New Orleans, you need to integrate yourself into a story that’s already there to succeed and prove to others you fit in.

Rm220: What led you to writing (in a general sense)?

BIJ: Ah – it’s the only way I knew to make sense of the world. Having folks who wrote didn’t hurt. I grew up with my single mother who always emphasized the importance of the written word. (See dedication.) It helps me understand the world. And I love to tell a good story.

Brendan Jones lives on a tugboat in Sitka, Alaska, and works in commercial fishing. A Stegner fellow, he studied and boxed at Oxford University. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Ploughshares, Popular Woodworking, and on NPR.