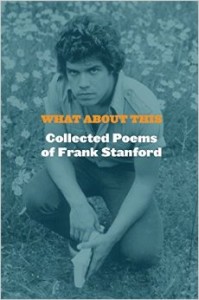

What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford, by Frank Stanford. Copper Canyon Press, 2015. $40, 762 pages.

You know that there are many poets around now. A lot of them seem to be fighting over this or that. I don’t really know. I don’t even know what makes me a poet. I certainly don’t want anybody telling me what does or doesn’t.

–Frank Stanford (from an interview with Irving Broughton, published in What About This)

The lore of the deceased poet Frank Stanford lies in his existence, not his death. His birth parents are unknown. The orphanage from which a single mother adopted him burst into flames, destroying his records. This is the beginning of any hero’s tale: a lone child cast downriver in a basket, given suckle by a she-wolf in the forest. You might say it wasn’t Dorothy Gilbert or Albert F. Stanford who raised Frank, but the river where they worked. The hills where they lived. The people living in the tents along the levee. Silt and dirt and fish.

Stanford’s cast of unruly characters—Baby Gauge, O.Z., Sho Nuff, The Albino, and the Rollie Pollie Man—acts as brothers and prophets in Stanford’s poems. Many of them, like Baby Gauge and O.Z., represent Stanford’s actual childhood friends from the levee camps of Mississippi. Some of Stanford’s characters appear in flashes, but most stick around, making appearances throughout his first collection of poems The Singing Knives and his 383-page epic poem The Battlefield Where The Moon Says I Love You. Stanford’s poetry has the nature of a deck of Southern tarot cards—the farmer’s daughter, the knife, the drunk, Death, and the levee are just a few emblems Stanford uses to express the potent archetypes of his mind. Like tarot cards, these images appear and reappear with changing situational significance.

Each poem’s intent to mean something is evident in the heavy-handed, totem-like characters and objects Stanford employs. To convey, Stanford often resorts to similes. They appear in his poetry the way a typical Southerner might use them in a story (smart as a whip, mean as a snake). Stanford stuns us with his unusual comparisons. In The Singing Knives, “Blood came out like hot soda.” In Belladonna, the feeling of falling in love is described as “A song that comes apart/ Like a rosary/ In the back of a church.” In Leer, something could “blow clean through you” … “and fade like some light saying Darling.”

It’s clear that Stanford’s poetry is not based in phrasing, word play, or tricks of the eye. It doesn’t dwell on cleverness, modernity, or resolutions. It’s instead based in the ancient art of storytelling, or as Southerners sometimes put it, telling lies. A good storyteller enchants his audience with description. Stanford’s ability to sustain imagery is akin to a jazz trombonist’s godly way of dragging out that breathiest, most boot-shaking note.

Bad food and dead children are not forgotten.

They smell like cod liver oil

In a thimble on the fingers—

A fat lady in a housecoat

Walking through rooms with a cage,

Calling a bird.

from “Lost Recipe”

Frank Stanford’s vocabulary is not exhaustive, which might be why some early critics described him as a hillbilly poet. But this hillbilly was extremely well read (he has poems dedicated to Raymond Radiguet, Julien Torma, Yukio Mishima, among others). This brings me to the conclusion he might have scoffed at poets employing overindulgent locution, citing it as unnecessary or reaching. Or maybe verbosity wasn’t his style. Stanford said, “I don’t believe in tame poetry. Poetry busts guts.”

One of my favorite scanned additions to the collection demonstrates this gut-busting quality, a two-line poem titled “The Warrior.”

I was born

I ride tomorrow

The “gut,” the center organs between our heart and our bowels, represents an intermittent place, where our first thoughts and last feelings collide. What does it take for Stanford to believe that a poem “busts guts,” and why does he insist that poetry to his liking must do it? When I read Frank Stanford’s poetry, it feels like something breaks inside me and a flood is let loose. By the time I was nineteen and had my hands on The Singing Knives, I needed something from it. I, too, had grown exhausted with volumes of poetry that gave me a taste of something real or scary, then backed away.

Stanford reaps much of his now-fame among followers from the visceral quality of his poetry—the blood, the knives, the violence—but anybody can write shocking verse. What I find most compelling is not plainly the haunting images of rats sucking the blood out of a baby’s head, or killing men with frog gigs, but rather the “Between Love and Death” quality of Stanford’s poems, the dance between light and dark.

The tide sifts out my eyes

Prison without hammers

Perhaps this is the root

Singing in time

And this is the crime

Living and dreaming

from “Cemetery Near the Sea”

In this dream world, there is lyricism. A southern drawl. But Stanford isn’t desperately pulling from the Southern landscape to paint us a regional picture. His poems exist there. Their language makes that existence evident.

The mosquitoes got drunk

And laid out on the moon’s lounge

So we stuffed light bread

Through the holes in the screendoors.

from “In This House”

In this poem, mosquitos and screen doors give way to wild horses, melon, and tadpoles. These images evoke my own childhood, running around on the “wet fields” that “give pleasure.” Somewhere in my dream-conscious I, too, have seen the “hats blow down the road like dandelions.”

Often, these images Stanford glints throughout his work are strikingly beautiful. Just as often, they are strikingly grotesque. Stanford doesn’t make judgments or assessments in his poetry. He exists and expels. I think of the fishermen I used to watch float down the Black River outside of Paragould, hands red with bloody fish bait from beat-up coolers. I think of sticking my finger into a fallen bird’s nest one morning before mass, the warm yellow insides of an egg running down my hand. I think of my mother and her broom sweeping teeming larvae out our back door during a thunderstorm. I think of the snuff my great-grandmother used to snort from a coffee can. Images in Stanford’s poetry appear to come from my own dreamscape, my own memories.

We’d been dreaming

Or at least I had

About peanuts that grow in the river

And oozed sap

When you bit them

A woman bootlegger shook her dustmop

That was the moon

from “Brothers on Sunday Night”

As someone who has read, loved, and collected Frank Stanford’s work for many years, I am so thankful for the release of What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford. Being from Fayetteville, Arkansas, where Stanford spent his early adulthood until his untimely death, I’ve always felt a special tie to his life, his work. Not only does this large volume include the contents of his many small books and chapbooks I’ve managed to hoard, but it also houses a sizable amount of unpublished work that would have otherwise disappeared. I find the photographs, lists, and bits of scanned typewritten minutiae throughout the book reveal who Stanford was without giving too much away. He’d probably like that.

Frank would point at certain people just to say, “I like you. I like you. I don’t like you,” and fire shotguns into the ceiling.

From what I’ve heard about him (old lies from Fayetteville folk who knew him or wish they did) he liked his privacy, or his mystery, whichever you want to call it, but that didn’t stop him from enjoying the company of strangers. He’d often go down to the only juke joint in town and drink beer with the blue-collar locals. He liked women, too. He had two marriages and a few affairs. Once, a friend of his told me Frank liked to eat Cheez-Whiz with pickled jalapeños. The same friend said he’d waltz through the door and say, “Let’s put on a pot of coffee and write all night.” Ralph Adamo in “The Long Goodbye“ by Ben Enrenreich says that at house parties, Frank would point at certain people just to say, “I like you. I like you. I don’t like you,” and fire shotguns into the ceiling.

College kids now flood Fayetteville by the hundreds, lighting up the historic square with their fluorescent neon tank tops. Wal-Mart executives build new cottages among the old ones, gas their Volvos at what used to be the Valero but is now the Road Runner. Frank Stanford’s name is among the living ghosts of old Fayetteville, before its charm and natural beauty were discovered by the masses. Local writers do what they can to carry on the memory of this Fayetteville by re-reading Stanford’s poetry, living vicariously through his work. They recall a time in Fayetteville when artists, writers, and hippies flocked to the town to get away from the big cities, and lived among each other happily cut off. There was even a Frank Stanford literary festival for a while, but it lost funding or attendees or both.

Visiting my parents’ house from New Orleans in the summer of 2010, I came across an essay about Stanford’s poetry online. I had been browsing for hours, and can’t recall the essay or where it was published. I remember reading excerpts from his poem “The Snake Doctors“ and feeling like I had to read more of his poetry immediately. At this point, I couldn’t find many of Stanford’s poems in the Google archives. I combed the Internet. All I got were clips of his poems, excerpts, essays. I needed more than that. On Amazon, a copy of Stanford’s collection The Light the Dead See, published by University of Arkansas Press was available for fewer than twenty dollars. A posthumous collection, it promised me a good amount of Stanford’s work to delve into. I clicked ORDER though I had about $50 to my name.

I felt spiritually altered by Stanford’s writing. His poems spoke to me directly. At the time I read him, I had become frustrated with my own work and the work of my contemporaries. His poems prompted me to return to my roots. His poems reminded me that poetry is still alive. I realized that I was guilty, in many ways, of writing what Stanford would describe as tame poetry. I was encouraged to explore a different canvas, my dreamscape, and the rich characters therein.

It wasn’t until halfway through The Light the Dead See that I realized Stanford was from Fayetteville. Upon learning, I set out on a hunt to gather information about this poet who had changed my poetic terrain so suddenly. At Dickson Street Book Shop, poet Matthew Henrickson gave me Stanford’s old address, along with titles of other Stanford collections and chapbooks published by Lost Roads Press (founded by Stanford and friends in 1977) that I needed to get my hands on. (I did.) As the sun set pink and vibrant orange, I drove to the top of Mt. Sequoyah, walked out onto the lawn of the little white house, kneeled down and touched the dirt. My pilgrimage.

Though his life was short, he was mind-blowingly prolific in his work. But if Frank Stanford were living today, and not already renowned, I can’t help but speculate that his work would be largely unpublished. Much of the contemporary poetry of today’s literary magazines has a worldly, often saccharine cleverness to it that Stanford’s otherworldly and earnest work refuses. His poetry doesn’t get hung up on the paltry corners of immediate existence. At the same time, his poetry is not so fastened to a made-up world that it is inaccessible.

It’s always possible that even if he were still alive, we’d have the same volume of work to read, that at some point, Stanford would have given up on poetry. Something tells me that it wasn’t in his blood to do that. That there were still stories to be told from the top of the levee, in the gut of the gar, and on the blade of the knife. My advice to anyone interested in poetry that busts guts: Read this volume. Become so hypnotized by the combination of beauty, familiarity, and strangeness that you begin to remember experiences that you haven’t yet had. Let reality give way to another kind of reality—one in which the tangible and the intangible collide. Lie down and listen.

Death means nothing to me

I think life is a dream

And what you dream I live

Because none of you know what you want follow me

Because I’m not going anywhere

I’ll just bleed so the stars have something dark

To shine in

from “The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You”

Ryan Burgess lives and writes in New Orleans. She teaches English at Lycée Français de la Nouvelle Orléans. Her work has appeared in Otis Nebula, under the gum tree, Cannibal, Heron Tree, and is forthcoming in Xavier Review.