-

Carmen Maria Machado, Photo Credit: Art Streiber / AUGUST -

Kimberly Pollard

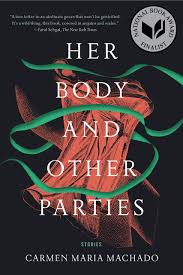

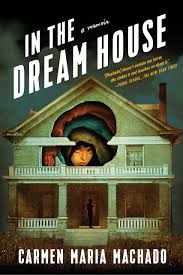

Carmen Maria Machado is the author of the bestselling memoir In the Dream House and the short story collection Her Body and Other Parties. She has been a finalist for the National Book Award and the winner of the Bard Fiction Prize, the Lambda Literary Award for Lesbian Fiction, the Brooklyn Public Library Literature Prize, the Shirley Jackson Award, and the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Prize. In 2018, the New York Times listed Her Body and Other Parties as a member of “The New Vanguard,” one of “15 remarkable books by women that are shaping the way we read and write fiction in the 21st century.”

Her essays, fiction, and criticism have appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, Granta, Vogue, This American Life, Harper’s Bazaar, Tin House, McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, The Believer, Guernica, Best American Science Fiction & Fantasy, Best American Nonrequired Reading, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and has been awarded fellowships and residencies from the Guggenheim Foundation, Michener-Copernicus Foundation, Elizabeth George Foundation, CINTAS Foundation, Yaddo, Hedgebrook, and the Millay Colony for the Arts. She is the Writer in Residence at the University of Pennsylvania and lives in Philadelphia with her wife.

New Orleans Review

The first thing I wanted to ask relates to the prologue and the introduction of Archival Silence, cases that are ignored or otherwise treated poorly by systems meant to protect them. And you also pose the question–how do we move toward wholeness? As a trauma survivor myself, I’ve found that so much of recovery is moving back to feeling whole, or trying to. So I’m wondering if you could talk generally about the form. Were many of them there from the beginning, or did they find their way?

Carmen Maria Machado

Yeah, some of them were ideas I’d had from the beginning, from the early stages of figuring out the memoir, some of them showed up later, some of them arose as I was writing. The Choose Your Own Adventure was actually very late in the process, because I had had this idea very early on that I wanted to have a chapter where it creates a tension in the reader and isn’t super friendly towards the reader. I wanted a chapter that sort of jabs at them orr otherwise creates stress within them, and it was really hard figuring our what to do. I tried doing something where I start talking to the reader as if I’ve said something that I hadn’t, and sort of gaslight them in that way, but really that was just confusing. So, eventually I settled on the choose your own adventure because it’s the ultimate illusion of choice, there’s an illusion that you can get out of something, when in reality it’s not–you’re given two very narrow options that have been pre-selected for you, and I love the way it allowed me to play with the reader. And I wrote that pretty late–it was one of the last things I wrote before I handed the book in.

NOR

I think absolutely the stress of choice is so present in those sections. On the note of handing it off–what in the transition from short fiction to longform nonfiction, what lessons or anecdotes did you take from previous projects and apply to this one?

Machado

They’re different kinds of projects, so editing them is different in many ways. With a fiction book, an editor can suggest whatever, they can suggest a character do something, but with nonfiction it’s harder, because the editors only know what you’ve shown them. So you feel a little more on-your-own. My editors are invaluable and they’re incredible, and sometimes he was just sort of “okay here’s what I’m seeing, now you’re left to your own devices.” Which is pretty unusual. Editing a nonfiction book is just harder, for me; fiction’s a much more pleasurable experience. My editor had to put this book in order, which was interesting. I had written all the history sections and all the essayistic sections in chunks, so he had to pull them apart. They’re really different processes.

NOR

Could you talk more about fiction being a more pleasurable experience?

Machado

I just find fiction more pleasurable in general.

NOR

On the note of the essayistic sections and the historical sections being all sort of intertwined, was the idea of archival silence–and your desire to uncover the histories you include in your memoir–was that an anchor of the project from the start?

Machado

Well, weirdly enough I think the idea of archival silence is not without that aim. I think the idea of giving myself context was present from the beginning, but the language of archival silence came fairly late, because I didn’t know it existed. My wife met somebody and was talking about what I was working on, and they said “oh, has she read about archival silence?” And I ended up in these really interesting essays and documents, but also it was a sort of academic framework I could put my finger on–and I was like “perfect!” I feel like that language came late, but the ideas were there early-on.

NOR

And did you find having the framework, the academic vocabulary, especially finding it later, did it help to clarify things? Had you been looking for the framework?

Machado

I wasn’t looking for it actively. Of course I had been doing all this research, but sometimes things just fall into your lap. It’s very strange.

NOR

Everything is very strange right now. Something I’ve been thinking about is that this book is about what it means when a home is the object of violence–in context of quarantine. Is this something you’ve been thinking about too?

Machado

It’s very relevant, and it’s a very interesting take on thinking about the home. Usually I’m thinking of it in context of the gothic, of haunted houses, and the idea of home being unsafe. But my own home is very safe and comfortable and pleasurable to be in. Ask me in two weeks if I still feel the same–but for me, I don’t want to be stuck anywhere, but I don’t mind being stuck here. It’s exactly what I want it to be, it has everything I need.

Kimberly Pollard (Loyola ’21) is an English/writing major at Loyola University New Orleans and a full-time barista. She reads as much as she can about women, families, and trauma.