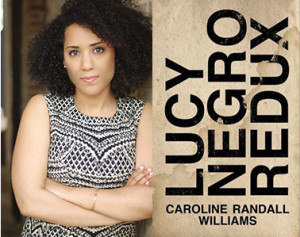

Caroline Randall Williams is a poet, cookbook author, and young adult novelist. She received her MFA from the University of Mississippi, where she co-authored the Phillis Wheatley Award-winning The Diary of B.B. Bright, Possible Princess and the NAACP Image Award-winning Soul Food Love. A Cave Canem fellow, her poetry has been featured in several journals, including The Iowa Review, The Massachusetts Review, and Palimpsest. Lucy Negro, Redux (Ampersand Books, 2015), is her debut collection.

Kristin Sanders: This is such an incredible debut book of poetry. But it’s hardly just a book of poetry; it’s a hybrid of historical nonfiction, research, Blues, children’s songs, deconstructed sonnets, and lyrical poetry. You’re as comfortable with prose narrative as you are with abstract lyricism. I want to avoid author-speaker conflation, so I tried to give you space for your narrator to have her own voice—and of course, at times in the book, you take on Black Lucy’s voice. But I have to ask: Did you really travel to England to do research? Is that the “I” of Caroline Randall Williams?

Caroline Randall Wiliams: I really did. And however quirky, charming, or eccentric a trip I’ve made it out to be, it was even more so.

KS: And, if so, can you talk a little about that experience? How long did you do research in England?

CRW: I was in England for about a week. I spent two days in Chichester with Dr. Salkeld; we drank very good scotch and talked about his wonderful book, Shakespeare Among the Courtesans, in which he presents much of his research on Black Luce. He gave me a crash course in Elizabethan longhand, and then sent me off to the Bethlem Hospital Library Archives, where I got to see the Bridewell prison records for myself. Dr. Salkeld met up with me in London the next day, and, using an Elizabethan-era map of London, we walked all through Black Luce’s neighborhood, finding all of the landmarks still standing from her day to ours. I spent the rest of my trip getting to know the neighborhood still better, and revisiting the archives.

KS: The premise of the book is that Shakespeare’s “Dark Lady,” from sonnets 127 to 154, is “Black Lucy” or “Black Luce,” a black woman who ran a brothel during Shakespeare’s time. So you researched this actual, historical woman, and from there, the writing extends out to different eras, situations, women, and identities. The book has this gorgeous timelessness. And yet it feels very timely, given the Black Lives Matter movement and the lifting up of Black beauty, Black bodies. (I’m thinking of Viola Davis’ recent Emmy award, and her moving speech.) Your final two poems, “This Exiat Sayeth That” and “Lucy’s Exiat Sayeth That,” are especially powerful given this racially fraught moment—even globally speaking, with immigration in the US and abroad, and terrorism, all of this “us versus them” reactionary, stereotyping politics. You write, “We are fit for the degree of them that use us,” and “Lucy is burning,” and “The answer Lucy the new look question and truth of all the things a dark lady can be” (71). And the final line of the book: “By God if you warm and eat me, I will nourish and fatten you” (72). Your book ends on a note of hopefulness and triumph. Did you try to cultivate that feeling for the ending? And did you think about our current political moment as you were writing this?

CRW: The short answer to your question is, of course. Yes. For me, writing poetry is an act of will, will to love life, love myself, love the world around me, even like it is. I work to put down words that will fortify that will in myself, and the people who read my poems. In the spirit of that intention, I very much wanted the end of my book to be both a celebration and a challenge, a reproach to those who pass unjust judgment, and an invitation to return, understand better, and judge again.

I cannot tell you what a thrill and a privilege it has been to see my book come out in the world of the Black Lives Matter movement. The thing is—and I know I’m treading familiar ground when I say this, but it must nevertheless be said—black lives have always mattered. The struggle has been to find a way to be heard. Black people have been crying out for their occasions eloquently, viscerally, beautifully, elementally, for a long, long time, and longer than that, too. The exciting thing about the movement, for me at least, is the way in which it has collected those cries, and turned them into this terrific chorus of strong, individual voices that could not now be silenced or ignored no matter who wished to mute or shun them.

KS: A lot of what you’re doing in this book is revising the canon—these famous sonnets—to bring in more diversity, to acknowledge that maybe Shakespeare literally meant a black woman and the canonical Western world should accept that; after all, as you point out, “He was terribly precise, that Shakespeare, and from all the words to call her by, he wrote black” (69). How else would you revise the canon? Which writers would you bring in to high school and college classrooms? I know you taught high school English in Mississippi; were you able to experiment with revisions of the canon during that classroom experience?

CRW: I don’t know whether my work has been so much to revise the canon as it has been to revive it, to bring it back to life in order to take a look at what was already present in the text. A redux, if you will. There are so many wonderful ways to read Shakespeare, so many layers, such room for interpretation.

As someone with a relatively formal background in the study of English literature, I have to say honestly that I can think of very few other texts that are at once as flexible, as immutable, and as imaginative as the the works of William Shakespeare. That his sonnets stand next to and in conversation with my readings, my riffs, and my questions is a testament to that fact. When he writes, “If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head,” you could argue that its a leap to think it is not a black woman; the kinks and waves and rounds of black woman’s hair are a natural image to conjure, are they not?

All of that to say, the canon is, in my opinion, terribly important, and students should know it, and (hopefully) find things to love within it, and then work to speak back to it, to cry out for the unheard voices, to make art that is its equal and its superior. Shakespeare stands alone for so many reasons; his work’s ability to hold the infinite, imaginative interpretations of its readers without compromising any of its beauty or its gravitas is one of them.

KS: Lucy Negro, Redux has a lot of desire in it: physical desire, sex, and bodies are very present, but also the desire to validate your research into Black Lucy. In one prose section, you describe searching for proof via puns in The Comedy of Errors as: “When you want something as badly as I want Black Luce to be the Dark Lady that Shakespeare loved, and loathed himself for loving, that little stretch becomes a welcome bridge” (24). Later in the book, you write: “I went back to the original works, the Dark Lady sonnets, with the intention of finding evidence enough that I might be satisfied. Shakespeare’s work had been enough for me before, and I will make them enough again” (62). I felt this thread of sexuality, or more specifically, sexual power, throughout the book, at times pulled taut and highly eroticized, and at other times more loosely connected to the desire that exists in words and ideas.

CRW: Well, I did read a lot of Freud in college. But in all seriousness, sex, sexuality, and sensuality are such an important part—for better or worse—of the ways in which women have lost, claimed and used power, from time immemorial right on through to the present day. For black women, especially black American women, and for this black American woman in particular, that truth is deeply complicated. I am light skinned because my white male ancestors were (most likely) rapists, and their victims were my black female ancestresses. That is an ugly truth. But I believe those women were beautiful. I imagine the white wives of the white men were jealous. I struggle with the small satisfaction I feel from that. I struggle with the idea of white southern men from the past who knew how to feel want for a black body, because I live in a black body, and know what it is to want to feel wanted. The parts of me that are genetically white are inherently political, and inherently sexual, in ways that are hard and strange and beautiful in the strength of the women who lived through those struggles.

Black Luce was a brothel owner, and did very well. She was the boss of who came—literally and figuratively—into her house—literally and figuratively. I love that. I love the idea of choosing how to live in your body, even if your choice might look ugly. What looks ugly changes. What feels deep-down good seldom does.

KS: Another thing I noticed about your writing of desire is that you include both sexual violence and pleasure, even joy, equally. I think that’s a rare quality in writing. In “Vitiligo Blues” your narrator, thinking of Michael Jackson, reflects: “I would’ve cut my face up too I would’ve stopped everything all my rapist forefathers crawling in patches onto my flesh like that I would’ve sliced my nose right off to spite them bleach my skin to show how frightening an invasion of whiteness can be” (34). And in “Sublimating Lucy. Considering Courbet.” your narrator hopes Eve’s genitalia, rather than being “a restrained little / tight pink little / gash,” instead “folded out / in tough, pliable furls: / Hello, Abel. / Hello, Cain. / It’s the beginning of the world, / that endless, human vessel, / and what is mightier?” (17). There’s a refusal of shame—an incredibly powerful refusal of shame.

CRW: Lucy Negro is a sin-eater. She is a shame-absolver. That is the idea, exactly. I hate the idea of reproaching someone for the ways in which they want to be wanted.

There is no one right way to be a human, no one true understanding of what is just or moral or even good. I am a Christian who knows very little for sure of what God wants besides love, and I don’t think anyone living could tell me, so I pray. I know very little of what my body wants besides love, and that is difficult to determine on one’s own, so I explore.

KS: Your book has nonfiction prose, Blues songs, children’s songs, sonnets, and lyrical poetry. How did you develop the hybrid structure of your book? What other hybrid texts or authors influenced you in your consideration of structure?

CRW: There was a moment when I thought I would have to bring Lucy into the world in fragments. I had the sonnets, I had the erotic, in-the-present poems, I had the essay about my research; they were all Lucy to me, but I had no idea how to bring them together in a way that would make sense for anyone else. And then I read Michael Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid. That book changed everything for me. Ondaatje himself has called it a “mongrel,” and it really is—a kind of hybrid beast that explores form and perspective and characters and voices in a way I had never seen before, and have not seen since. Reading it was an experience of being granted both permission to try and make it all work, and a loose model upon which to rely as I undertook the adventure of organizing the book.

KS: You recently published a cookbook, Soul Food Love, with your mother, Alice Randall, who is also a writer. You and your mother also wrote a YA novel. I love watching your career grow, and I feel like you’ll always be surprising us with your next move. What do you have in the works? Will you return to poetry? This is such an amazing debut—intelligent, thoughtful, lyrical—that I can’t wait to see what else you do with poetry. (And cookbooks. And YA. And…)

CRW: I took a little break from writing poems—Lucy winded me a bit, if I’m very honest. I’ve started writing again, and have surprised myself with what’s come out at this stage. I won’t say more than that just yet, but I am excited about the truths I’m feeling called to tell. There is also a YA novel in the works, but I’m keeping that story close for now. My heroine and I are still getting to know one another; I’m not quite ready to introduce her to anyone else!

Kristin Sanders is the author of This is a map of their watching me (BOAAT, 2015) and Orthorexia (Dancing Girl Press, 2011). She is a poetry editor at New Orleans Review.