INTERVIEWER

How has teaching affected your writing?

FOUNTAIN

It’s complicated. One of the things that sticks in my mind that I heard someone say in graduate school, I think it was Marie Howe, was: don’t let anyone tell you that teaching has anything to do with writing. It really doesn’t. Writing being something that you do alone in a room and teaching is not that. If anything, on a very basic level, it takes away time from your writing. And then you add parenting to that—my husband and I just had our second child this summer.

INTERVIEWER

Congratulations.

FOUNTAIN

Thank you, thank you. A little boy. We have a three-and-half year-old girl and a six-month-old boy. And…that’s a lot. It’s just a lot. And it becomes harder and harder to protect the writing time. I know plenty of people who just do it [teaching]—and it just seems to feed their writing. Even if it’s only in that teaching and academia put you in a place where you’re in a community, sometimes a much wider community where you’re in contact with other writers and poets. And that is a good thing about academia, but it’s still hard to manage it. It is exciting, too, with students—I have had a couple students come through in the time that I’ve been teaching, five years, who I’ve thought, wow, you should definitely pursue this…beyond.

INTERVIEWER

Students who come through and have the same kind of passion or spark.

FOUNTAIN

It’s not so much passion—there are plenty who have a lot of passion and who have conviction about their own writing—but just to see talent, a talented writer who makes you think…yes, you can do that. And that’s been exciting.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have any exercises that you do with them that have worked out particularly well? Assignments that you’ve given?

FOUNTAIN

I feel that with beginning writers any exercise where you can place parameters so that they’re focused on something is effective. That’s your job as a teacher, to point out the aspects of craft by constraining the students…otherwise they don’t have any direction. So, we have exercises that we do throughout the semester.

INTERVIEWER

Absolutely. That’s something that I’ll do for myself, too, when I haven’t written in a while is I’ll set myself a specific task. And I also give myself permission. I give myself permission to write a terrible sonnet. I sit down and write a terrible sonnet. And then I feel somewhat better about having gotten that out of the way and then continuing on to do something else.

FOUNTAIN

That’s something really great. Also, trying to remember that 90% of what you write will never see the light of day. William Stafford, said it best: “Lower your standards.” Just, lower your standards. Naomi Shihab Nye brought William Stafford to me—she gave him to me, when I was studying with her and I keep him very close by, his writings about writing are really great. So I try to take that pressure off and try to find the joy in writing and being with my thoughts.

INTERVIEWER

It seems sometimes that even that aspect of writing I have to have a kind of running start at. Maybe it’s the same for you—I feel like I have three jobs, including one at a nonprofit, and only one of them is paying anything. And I have to take a couple hours to just sit around before I can even be in the right headspace.

FOUNTAIN

It’s all about time. Time: the most valuable thing for a writer. You have to allow yourself that time to fail. You’ve got to have time to fail before you make something.

INTERVIEWER

You mentioned William Stafford—is there anyone else that you turn to?

FOUNTAIN

I always return to Merwin. Always Jane Kenyon—I love her work. I really love this poet Adélia Prado, a Brazilian poet. She is wonderful and Tupelo just put out a second collection in English of her work. She has about eight books in Brazilian Portuguese: Ellen Doré is her translator. Wesleyan released a book of hers in 1990 called The Alphabet in the Park, a very slender volume, and her second volume is Ex Voto. And I haven’t had it in my possession long enough to return to it again and again, but I have read it twice. So gorgeous. She’s a wonderful poet.

I love Neruda. I love Marie Howe. Her voice is very large to me. I feel like I could return to that voice again and again and be renewed by it. And then there are books that I’ve read in the past year that have knocked my socks off: Eduardo C. Corral’s Slow Lightning. I loved Christian Wiman’s Every Riven Thing. Some not coming to mind right now. Laura Kasischke, she’s a Midwesterner, a poet, really dark and wonderful; she’s also a novelist.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a common thread among these poets? A voice?

FOUNTAIN

Now that I’m listing them, I realize I put a lot of these on my syllabus for a graduate seminar I taught on spiritualist poets, poets who in some way seem preoccupied with the line between the sacred and the secular, or lean somehow toward the sacred. Maybe that’s part of it, that their concerns are more metaphysical. But perhaps not entirely. I think Laura Kasischke would probably die if she ever heard herself described that way. But most poetry does that. It’s hard to say what that means, but trying to utter the ineffable, that’s what everyone is doing. That’s maybe a throughline.

INTERVIEWER

So is uttering the ineffable, looking into the metaphysics, does that relate to your new book? Is that a line that you’ve been pursuing?

FOUNTAIN

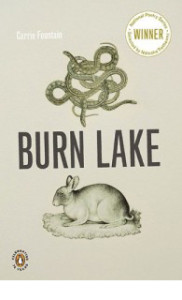

I don’t know. Because when you write your first book, you’re in graduate school and you’re sending it out for a couple of years at least. And you’re showing it to anyone who will read it, saying “Please, read my book, please!” A lot of people had read Burn Lake before it was published, but my forthcoming book hasn’t had a lot of eyes on it.

And honestly I’ve had a couple of people who’ve been trusted readers who kind of don’t seem to get it—because it doesn’t seem like Burn Lake. The preoccupations in this book are different. It’s about the existential shift that happens when you have children. So I think it’s even more exclusively preoccupied with spiritual questioning. Burn Lake is a really spiritual book but no one seems to think so! I guess that I can think whatever I want to think about it, but it’s a little more explicit in this book. There’s a series of poems throughout that are kind of like prayers.

It is different and I would hope that as we continue writing and learning our voices as writers, that we get closer to it and closer to our true voices. I think this book is a half-step closer to the voice that I would aspire to be creating in my work. So it’s a little bit looser and a little deeper, like a lower register in some way.

INTERVIEWER

Your first book very much stood out to me from the other first books. It was very straightforward, and it did seem to grapple with what is beyond this, why are we doing this, what do these relationships between us mean. I remember you said that with Burn Lake that you’d initially been somewhat reluctant with the narrative direction it seemed to be going in. Did Instant Winner turn out to be narrative as well?

FOUNTAIN

It’s entirely personal—it doesn’t have poems that I did research on to complete a frame, which is kind of what I’d hoped for Burn Lake to do as well.

INTERVIEWER

Are these poems structured differently?

FOUNTAIN

I guess a lot of the poems are narrative. Some of them are a little more lyric, not relying as much on story. But it’s a hodgepodge.

INTERVIEWER

Reading essays, following various literary magazines and reading their interviews, it seems like narrative poetry is almost out of favor.

FOUNTAIN

Unfashionable. But I’m not sure. People who are writing crazy forms and post-modern poetry probably think their poetry is out of favor. And people writing narrative think their poetry is out of favor. I think people find they have a core group of audience members and write for them. Honestly, I’m not that interested in that conversation.

For a while, I was writing reviews of poetry collections in order to make a little bit of money and as a way to read books of poetry and to think about poetry. But I struggled to write them—to the point that it would be ridiculous. And we’re talking about reviews for the Austin newspaper. So they weren’t like 5,000-word, super interesting annotations on some of these works. They were very simple reviews. And finally I realized why I had such trouble with them and why they made me very unhappy: I don’t want to be the arbiter of what is good or what is bad. I just want to read poems and write poems and have conversations with poems and poets. I think that we’re very preoccupied with what is in favor or out of favor and it becomes less and less interesting to me.

INTERVIEWER

Absolutely.

FOUNTAIN

I have this ongoing conversation about life’s challenges and goals: what if you could like everything? Some people find that very offensive, that it’s sort of simple or falsely simple. But it’s a really difficult thing to try to like everything and to find value in everything. Because it gives us confidence sometimes to say: this is good and this is bad. It can give us a certain amount of confidence: I know what is good; you don’t know what is good, so I’m in a position above you. What if we didn’t do it that way? What if we could learn or try, as a goal, to just like everything? I think that strikes some people as being very dangerous, like you would lose all your critical capacity and just be a fool. But it seems like a very spiritual challenge.

INTERVIEWER

I think last time we talked you mentioned trying to appreciate or learn from even those writers whose style you didn’t love. But it’s also very difficult advice, at least for me, to follow. I want to be bowled over. And I have trouble sticking with things unless I’m bowled over.

FOUNTAIN

As do we all, as do we all. I admit it’s more of a theoretical than a practical idea.

INTERVIEWER

Sometimes it just takes another person. I’ve prematurely dismissed a work or poet, but then someone has absolutely loved that work or that person and suddenly that personal connection opens me up to it. Which is what a really good teacher can do.

FOUNTAIN

That’s one of the wonderful things about teaching. If you can find a way to teach what you want to teach, that can be a really rewarding thing. I think so often we get stuck teaching things we don’t want to teach.

INTERVIEWER

I’ve actually been missing teaching the last month or so.

FOUNTAIN

See there you go! You should just send out an email with an idea, it doesn’t even have to be an idea—it can just be, “Hey I’d like to do a private workshop out of my house: four weeks, we’ll do some writing.” Organize it and people will come.

INTERVIEWER

Let me ask you ask you a question, especially as I’m a recent MFA grad. What does it mean to be a poet or to call myself a poet, to think of myself as a poet outside of that MFA context by which I was defined or defined myself for the past four years?

FOUNTAIN

I think it has so much to do with identity. When I was in graduate school, Charles Wright came to visit and said, “It’s not what you do in graduate school that matters.” And of course, we’re all working ourselves to bone. “What matters is what you do after graduate school.” And I just thought: “You’re killing me here!” But now I get what he’s saying. I think it’s valuable to live in a place where you’re not being defined as a poet and you’re not, you know, in an MFA program. Ultimately, you have to discover those things for yourself: what does make you a poet? Is it that you’re in a graduate program with a bunch of other poets or people that call themselves poets? Or is it that you’ve published a poem? Or is it that you wake up every morning and work a little bit? Or is it that you have a process with which you engage and which you want to look upon the world? You have to answer all those questions for yourself, and it’s easier to do that when you’re in that program.

It’s very hard after you graduate, figuring out who you are, who you were, who you want to be. I think that many of us are still figuring that out, outside the universities where theoretically we would be teaching poetry, teaching writing for the rest of our careers, and publishing books. I’m still trying to figure out what I am. What I am during the day…and what I am at night? Then there are all these other complications—such as, what I am is a mom. And a wife. And a homeowner and an insurance policyholder trying to figure out a claim for a guy that ran into my car the other day. So, in some ways it’s easier to define oneself in a creative writing program. But I think what Charles Wright is trying to say is that what really matters is what you do after the reality of things settles in. Because that’s what you gotta do. You gotta keep writing. Wallace Stevens. William Carlos Williams. They weren’t teaching poetry. Their daytime lives belied their identities as master poets.

INTERVIEWER

The double identity.

FOUNTAIN

And that can be valuable. And it doesn’t take away. Your identity as the development person at a nonprofit does not take away from your identity as a poet. It only enriches it. You’re a citizen of the world, that’s all you are. It doesn’t make you any less of a poet that you’re not teaching poetry. There’s always a point in my semester when I’m looking at my students thinking, “I’ve been reading your poems for weeks and weeks and weeks and I haven’t written any! What the hell am I doing here? How can I be surrounded on all sides by poetry and not have enough time to work on my own stuff?” What matters is that you sit down and you keep writing. That’s all that matters.