Interviewed by Sarah Smith and Marcus Smith in 1975.

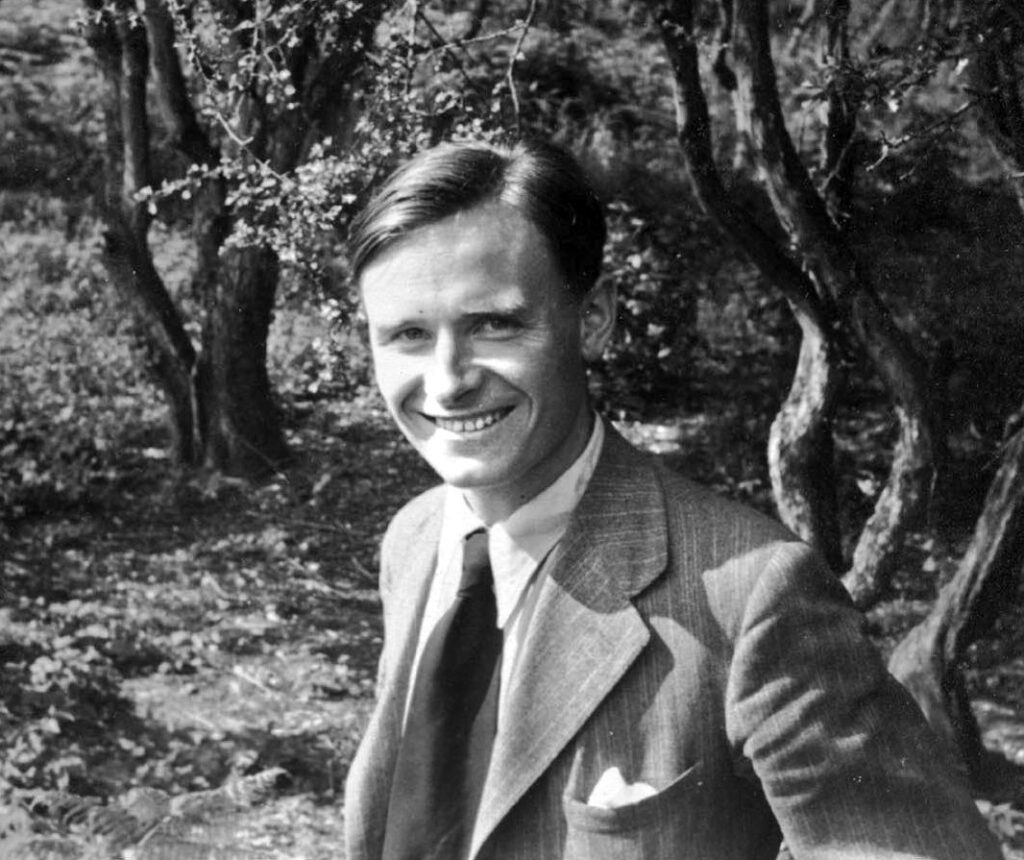

Christopher Isherwood was born in England, is now an American citizen, and resides in Santa Monica, California. He is the author of many novels, plays, translations, and autobiographical books.

New Orleans Review

There seems to be a general fascination today with the Weimar Republic. Not only are scholars studying its collapse, but one also encounters a rather widespread popular fascination with that period of German history. Could you reflect, in terms of your own experiences, on the state of society and politics of that time and the United States as you see it today?

Christopher Isherwood

To tell you the truth, I don’t see very much relation between the two. I never have. I’m constantly asked, “Do I think the Nazis are coming?” The answer is no, not in any way which could be compared to the ending of the Weimar Republic. Perhaps this is due in part to a sort of irritation I feel toward doomsayers. My experience in life has always been that while you’re watching one mouse hole, the mouse comes out of another. Since I’m not in any sense a political observer, and wasn’t in those days, I only go on a kind of instinct. But I find the capacity of this country to remain more or less afloat almost infinite considering the things that have happened.

NOR

Is this merely economic luxury, the fact that we can afford stability, or is it because of some cultural or spiritual quality?

Isherwood

It must always be something psychological. It must be something in the inhabitants. I remember so well, for example, in Colombia, when I was there in 1947, several Colombian intellectuals said to me, “Our respect for the Constitution and for the principles of democracy is the only thing that makes us superior to Paraguay.” Barely four months later there was the most appalling civil war in Colombia. General Marshall was visiting and had to get out of Bogotá, along with other American representatives. A very popular politician named Gaitán had been murdered, and as a result, there was a tremendous slaughter in the streets. I always felt in South America this could happen to any of the countries that we were in. I don’t say that North Americans are necessarily more law-abiding. It may be partly a sort of saving streak of apathy. I don’t know.

NOR

What about the young people today who have such a deep hunger to believe? It seems that anything can be packaged and sold to them.

Isherwood

I have been appearing on campuses for many years, and something has developed in the last fifteen years or so. The young are constantly asking about religion. They want to know. And I never try to push it. I never try to say more than I dare. I never try to seem holy or pretend to have knowledge beyond the absolute basic thing about which I can say, “Well this—I really promise you—I believe this much.” If you try to fake anything, they see through it instantly. Stalin was in a theological seminary when he was young, and needless to say, he left. Gerald Heard used to say what an awful tragedy it was that there hadn’t been anybody really spiritual at that seminary. Obviously Stalin had seen right through the whole lot of them and had therefore decided that religion was indeed just the opium of the people. I think it’s frightfully important, and this is really much more difficult than it sounds, only to say what you absolutely believe. I mean, never to kind of skate around difficulties; if you feel that there’s a difficulty, you say honestly, “I don’t know—I would like to believe that or think that, but I’m really not sure myself.”

NOR

How does one communicate to others a sense of mystery without specifically saying this is the mystery that one ought to believe in?

Isherwood

Well, I’m absolutely sure that everybody has a natural sense of the numinous, of something mysterious, something that awes you, beneath the appearances of things.

NOR

How does this relate to your interests in Vedantic studies?

Isherwood

I cannot say too often that I am not in any sense a guru, anything of this kind. I never set out to be. I am simply somebody who is able to write the English language a little better than a lot of people, and as such, put my know-how at the service of this monk, Prabhavananda, who is also my guru. This is a very, very different thing. I mean I never did anything except just put into rather more readable language what he said, what he taught me, and everything that I ever wrote about it was very carefully passed on by him and indeed by the head of the Order, and all sorts of people in India (in the case of the book about Ramakrishna). So that you can hardly call that independent writing in the sense of making something up or even thinking something out.

NOR

Do you then regard yourself as simply an editor?

Isherwood

Well, really, yes—not much more than that. I mean, the only Vedanta book to which I contributed anything of my own (other than in a purely stylistic way, such as in the choice of words) was How to Know God, the commentaries on the Yoga aphorisms of Patanjali. In that book from time to time, I would think of illustrations, examples, things that would appeal to Western readers, or make comparisons with things said in other literatures on the same subject. That was about the extent of my contribution, really. You see, Prabhavananda speaks very good English. And he’s also spent almost all of his adult life in the United States. He came to the United States when he was just thirty, has been here ever since, and he’s now over eighty. So naturally, he has quite a way with the English language. He has very little opportunity even to speak Bengali except to his two assistants; most of the time he’s speaking English.

NOR

You mentioned that you did not regard yourself as a guru, and even suggested that you disliked being cast in that role. Do you see yourself as a seeker? Are you pursuing mysticism? Have you achieved what you think is a . . . ?

Isherwood

What I’ve achieved is open to question, but there’s no doubt in my mind whatsoever that I am a believer and a disciple, and that’s only strengthened with the years. The degree of my involvement is apparent when I try to imagine myself without it. That would be like taking away the whole frame of reference from my life.

NOR

Do you practice yoga, and if so, what type?

Isherwood

Oh, just a very simple form of meditation. I don’t practice hatha yoga, the exercises, although I have done them in my time—I took some lessons. The general attitude of our particular group toward the hatha yoga physical poses is that they are okay—many of them are like the exercises you are given in a gym. But we very much frown on the breathing exercises, because if you really practice them hard—that means hard—you may very well bring on hallucinations and psychic, as opposed to spiritual, visions, and this may lead in its turn to your becoming mentally unbalanced.

NOR

You mentioned a particular group. Which group is this?

Isherwood

It’s the Ramakrishna Order, one of the largest orders of monks in India. The Hindu monks I’m associated with are members of the Order who have come to teach here, not as missionaries but simply in an informative capacity. You see, as a matter of fact you could quite well be a devotee of Jesus of Nazareth and be a Vedantist at the same time, just as it’s entirely possible to be a Quaker and not be a Christian, because this belief that the Quakers have about the “inner life” is really nondescriptive. The enormous majority will say, “Yes, it’s something to do with Jesus,” but, if you really get down to it, it isn’t, necessarily. So this is a situation where it’s not necessary to make these kinds of choices, and there’s no question of being a missionary if you don’t have to “save” people from something. That was what always upset the Christian missionaries in India so much, because they would come to India and they would preach, and they were listened to by Hindus who said, “Yes, we see that Jesus of Nazareth was a divine incarnation, an avatar, and we shall worship him.” But what upset the missionaries so much was that the Hindus went right on worshipping other divine incarnations as well. The missionaries said you can only do it through Jesus. They replied that that’s perfectly all right, that Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita said, “Nobody comes to the truth except through me.” But of course, when an avatar says “I,” he really means that he’s a part of the eternal—it’s quite a non-personal statement. And so you go back and forth and sideways and upside down, and some people find this a terrible sticking place, and that’s why you find people who feel that the Hindu thing is unacceptable. But the Hindus are more than ready to accept the Christians, if by Christianity you mean the special cult of Jesus of Nazareth rather than of somebody else. Because for the people who are inclined toward devotion, a cult is of course necessary. I mean, this is in itself a way of knowledge. The word yoga is also used without any reference to physical exercises to mean different approaches to religion. This devotional approach is what’s called Bhakti yoga. Then again, there’s what they call Karma yoga, which is what we call “social service”—it’s what the Quakers are doing all the time. This is to say you see the eternal in your fellow men, and therefore you serve them, not because you’re helping your fellow men—that’s a terrible egotism: if anybody is being helped it’s yourself, for having the privilege of serving God in these people. Then again there’s another path, which is much more rarified, called Jnana yoga. This is a path of intellectual discrimination where you don’t actually worship anything but maintain a state of rigorous discrimination—always asking yourself, “What is the reality?”; “What is unreal?”; “What is real?”—to arrive at a state of enlightenment. I suppose this is true, for instance, of people like Krishnamurti, if you’re familiar with his lectures, because he’s always analyzing. All these different attitudes you can find in Christianity, in a way; you have the three yogas represented: the intensely devotional attitude of somebody like St. John of the Cross, and the intensely intellectual attitude of the Jesuits, and the “serving” orders such as the Franciscans . . .

NOR

It’s a question of choosing what’s right for you?

Isherwood

Exactly. As a matter of fact, Vivikananda, who is one of Ramakrishna’s chief disciples, always said he wished there was a different religion for every single being on this earth. In other words, he felt that you shouldn’t try to force yourself into joining something; you should evolve your own attitude toward the unseen. And he said that everyone’s attitude should be just a tiny degree different from everybody else’s.

NOR

How are you supposed to work this out? Do you have to have somebody who helps you—somebody to follow?

Isherwood

Well, of course I’m very much in favor of a guru, that’s to say somebody to help you along the line. I personally can’t imagine I could get involved in anything without meeting somebody because I’m that sort of person—I understand things through people. I used to infuriate my intellectual friends by saying, “I should have understood Marxism if I’d met Marx.” Or Hegel, or anybody you’d like to name. The British philosopher Freddy Ayres was telling me that he’d been down to lecture at Washington. And I said, “What on earth did you say to them?” And he said, “You come around for lunch tomorrow, and I’ll tell you.” And before lunch he sat me down in a chair, and he gave me a lecture. For almost the whole lunch afterwards, I understood his philosophy perfectly . . . But then gradually it all faded away. I even had a friend once who met Einstein and that happened. He was mad with excitement—he rushed to the phone, called his wife and said, “I understand relativity!” Einstein did it very simply: he took out some matches and laid them end on end, smoked his pipe and explained— and it was almost within my friend’s grasp.

NOR

In your lecture last night, you were discussing Cabaret and said you were unhappy with the bisexual play that Michael York involved himself in. You didn’t like that. You seemed to be saying that there are certain absolute categories: one is either heterosexual or homosexual, and there should be no casual crossing over.

Isherwood

When I was discussing Cabaret, I was criticizing much more the way that something was done, not what it was that was done. I’ll tell you what I do dislike, and this of course is admittedly a slanted thing. I dislike people who find it cute to make little sallies from the well-guarded fortress of heterosexual respectability and who then come back and say, “What are the homosexual tribesmen out there fussing about? What are they complaining about? Sure, I’ve had my little flings, and I’ve done this or that. Why are they so serious about it?” What these people don’t understand is that they are being sheltered by the public heterosexual side of their lives; they are protected from anything horrid ever happening to them, from ever coming under any kind of stigma, and by insisting to everybody else, to other heterosexuals, that that’s of course the important thing and the other is just a kind of game. They even get a certain approval. People think, “Well, he’s really a devil, he goes in for anything, he’s marvelous, he’s a swinger.” But what they mean is a swinger swinging very heavily to one side rather than both. Now all of this will be absolutely, utterly unimportant in the Kingdom of Heaven, or even in a genuine democracy, but it’s just a little bit distasteful to those of us who are actually suffering from this persecution, which is very real.

NOR

The young boy in A Single Man is to some extent playing that game.

Isherwood

Yes, and I deplore this, too, very often because it’s an attempt to pass. Of course, when I say “deplore” and all these angry, superior words, I have the greatest sympathy for anybody who tries to wriggle out from under an intolerable situation, if he finds it intolerable. I have the greatest sympathy for a Black who tries to pass. Passing exists in one way or another in every minority. It is not confined to the homosexual by any means. And of course with Jews, too, you’ll find it again and again—they assume those Scots names. All right, good luck to them. You see, when there was a question of making the film Cabaret, first of all there was another company doing it, and they asked me and my friend Don Bachardy to do a treatment. And after great deliberation we made Chris a heterosexual, for that very reason. We thought, let’s not have any “chi-chi” about this. There are only two tolerable positions: either Chris is one thing or the other. If Chris is a homosexual, this of course alters the whole story and is indeed an absolute fountain of dramatic situations which don’t occur in the book because I was sort of fudging. I was fudging for a rather different reason; I wasn’t trying to conceal the facts. I just didn’t want Chris to be an important character; I wanted him simply to be the narrator. And a character who is a homosexual becomes from a fictional point of view too interesting, too important, too way-out. Especially at the time when I was writing. What I wanted to say to the audience was, “Don’t mind me, I’m just telling you the story.” What I don’t like is teasing the audience—equivocating and trying to make something a little bit naughty. People always say about Berlin in the 1920s, “Oh, it must have been so decadent!” All they mean is homosexual.

NOR

Do you regard your fiction as outstanding from the point of view of the technical evolution of fiction? Do you think that you tried to push forward the form of the novel?

Isherwood

It never occurred to me. Anything that I might have done in that way, if I did indeed do anything, was purely a side effect. What I was concerned with was just trying to say what I thought was interesting about my life. A fan letter that I like almost better than any I’ve ever received was oddly enough from a war hero who had become some kind of big wheel in British aviation in later life. He said, “You try to describe what it’s like to be alive.” Of course, that was a thing that Hemingway was constantly doing—it was his whole stock in trade.

NOR

But didn’t Hemingway always get his sense of being alive by juxtaposing something that was dead, or in the act of killing?

Isherwood

Well, because he was intensely interested in danger and courage. I enormously admire some books by Jack Kerouac. In a sense I find Kerouac more interesting than Hemingway because Kerouac tells you about the physical thing but also goes into fantasies and philosophical speculations, mysticism and everything. I very much like The Dharma Bums and The Desolation Angels and Big Sur. Fiction or nonfiction is not a very important distinction to me, and Kerouac could have said the same. Kerouac was practically nonfiction, and Hemingway was frequently very close to nonfiction.

NOR

What about your own work? Has there been a shift toward or away from nonfiction?

Isherwood

I find the difference between my fiction and nonfiction slighter and slighter. The difference is diminishing. Because what I’m really interested in is commenting on experience.

NOR

Would this hold for, say, a novel like A Single Man?

Isherwood

Well, it’s almost entirely a comment on my own experience. But I’ve hardly ever in my life written about anything that I hadn’t done.

NOR

And yet at the end you try to go beyond your own experience—even into the mystery of death.

Isherwood

Yes, well, I mean, since it’s a mystery, everyone has the right to have an attitude to mystery. That’s all it amounts to. The actual scene of the coronary occlusion is lifted out of a splendid book called Man’s Presumptuous Brain by Dr. A. T. W. Simeons.

NOR

Isn’t there also an echo of Auden’s poem on Yeats? You talk about the various parts of the body deserting . . .

Isherwood

Oh, yes, “the provinces of his body revolted.” Well, you see, not only were we very close friends, but Auden as you know was the son of a doctor, and I was a medical student for a short time. One of the many, many connections we had was that we were both very interested in medicine and therefore rather looked at things in the same way. As a matter of fact, you’ll find similar images in a passage in Man’s Presumptuous Brain. So I just rewrote that, and I asked some heart specialists about it. In fact, one was so pleased with the result that he always reads the ending of A Single Man aloud to his students when he’s lecturing on coronary occlusions.

NOR

But you go beyond a heart attack and have George’s soul or spirit or his unconscious that’s gone out to sea come back and find the dead body, his own dead body there, and presumably then have to confront eternity.

Isherwood

Well, that’s my guess at it. But what I was going to say was that after all, what does it all amount to? If you write about your own experiences, you turn them into fiction I guess for two or three reasons: one is that experience is so messy; there are far too many people around; things don’t fit together very well; and you very often tidy things up by simplifying them in order to tell a narrative. And this involves eliminating characters, and you gradually pass at least in a negative way into fiction. So that’s one way, which is the only difference as far as I’m concerned. Secondly, of course, there’s the question of discretion. It’s only recently, for instance, that I could write with the extreme frankness that I do now on the subject of homosexuality.

NOR

Why is that? Is that a personal decision, or is it because of changes in society that allow you to be frank in that respect?

Isherwood

I suppose in a way I was sort of moving toward it, and I’m very much a child of my time in that way. I mean I go at the same pace as other people. But quite aside from that, what I have to say now wouldn’t be nearly as good if I’d said it in fiction. Because what I’m interested in is not revelations either about physical acts or about specific lovers, but really studying the psychology of my whole outlook on life, which I realize is far more influenced by my homosexuality than I’d ever supposed. And I begin to see that every word, in a way, that I wrote about Berlin and everything, is all very slightly off. It’s not absolutely focused.

NOR

Because of its accommodation?

Isherwood

Yes. To give you just one very simple example, it immediately branches out into sociology and politics much more than anything else. You take the whole of my relationship with the working-class movement, or let us say, Communism. Now, on the one hand, you get a situation where for sociological/sexual reasons—that’s to say because I was a kind of upper-class boy brought up in a nicey-nice home—I was drawn to another class. And in order to be drawn to another class of course, you tend to accept the politics which represent the cause of this class. So you tend toward socialistic or Communistic attitudes. But when you look toward actual Communist states, or toward the labor movement in many countries, you find the deplorable fact that they are exceedingly puritanical, and that they want to impose a heterosexual dictatorship just like the capitalist dictatorship. And so you see this is a very intricate pattern, and it causes a lot of bounce back and forth between two attitudes. The question is, are you going to say “my dictatorship right or wrong,” or are you going to say “my tribe before everything else”? Also, of course, it’s acutely embarrassing to recognize the dimensions of your tribe, because some of the people in it you’ll find deplorable, just as Jews suffer embarrassment over some Jews, and as I’m sure is the case with Blacks, and, well, with any minority one could name. But, to return to the question of fiction and nonfiction, nothing is more fascinating than the enormous complexity, the subtlety, of certain kinds of fiction. You couldn’t have a nonfiction Henry James; it wouldn’t be the same thing at all. His sensibility, of course, when he’s writing the book about coming back to America, The American Scene, is terrific, but there’s an element in James that you couldn’t possibly have except as fiction, because it’s necessary to have a lot of invention and a sort of crystallization of the situation. And that applies to a great many writers.

NOR

You’re working, I understand, on a new autobiography?

Isherwood

Yes, you see Lions and Shadows ends when I went for the first time to Berlin in 1929. And this new book starts on that day and goes through a period of about ten years, to when I embarked for the United States in 1939.

NOR

Do you have a title?

Isherwood

No, I haven’t got a title yet. I don’t know what to call it. My working title is Wanderings, but that’s just simply because you have to call a book something when you’re thinking about it yourself. Either this will be a complete volume in itself, or it will be connected up with a second volume which is about my first three or four years in the United States. Now that’s much easier for me to write because I have extensive diaries which I kept at the time. This first section is very difficult because I’ve forgotten an enormous amount, and I’m reconstructing it out of letters and bits of my diaries, of other people’s memories, which are wildly unreliable—I’m always checking up. Auden didn’t even know the year he married Erica Mann—he got it quite wrong! But of course there are always people who love to check these things out, and by degrees I’m zeroing in on most of it.

NOR

Is there anything you’d care to say in conclusion?

Isherwood

Did I tell you my exit line? I was speaking a few days ago, and I was trying to figure out how to leave the podium. I suddenly paused, and I said, “I had this great friend, the actress Gladys Cooper, whom I loved dearly (she’s dead now), and she was being asked about acting because they were talking about method acting and she was very scornful. And she said, ‘It’s ridiculous, there’s nothing to it. You just know your lines, and speak up, and then get off the stage as quickly as possible.’” As I said this, I walked off!