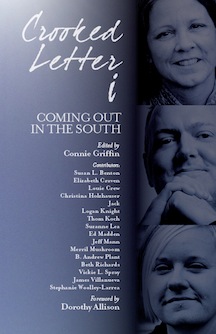

Crooked Letter i, Coming Out in the South, edited by Connie Griffin. NewSouth Books, 2015. $10, 208 pages.

Crooked Letter i, an anthology of personal essays edited by Connie Griffin, sets out to construct a narrative in which queerness and southerness are inseparable. The sixteen true stories in this collection build a historical framework for southern queerness, navigating through McCarthyism, the whiplash of AIDS, and a generation forcedly literate in a post-AIDS society. Watching each generation hide behind different fears—the persecution of the other, the ravages of an unfamiliar and lethal disease—gives volume to voices that were never allowed to tell their stories and perspective to those of us who are able to speak freely about our sexuality today. Authors such as Logan Knight and Beth Richards exemplify in their stories the unexpected expansion of acceptance in Southern families and communities. Essays by Christina Holzhauser and Susan Benton provide reminders that the South is a region pervaded with strict religious moral standards that create challenges for coming out. Multiple voices, experiences, and geography create an effective way to tackle the multifaceted beast that is the South.

Some of these stories are deeply personal, divulging the details of aching, of heartbreak and love that so often pair themselves in the southern queer narrative, and seeing this honesty allows safety for those reading who have never let themselves live that honesty. These stories feel like a carving the author has offered to the reader.

In Christina Holzhauser’s “The Answers,” she weaves love that is new, immense, and consuming with her confusion from a religion that condemned her sexuality. She grapples with this when she says, “I had considered my fate of burning for eternity, wondered if it was only painful for a little bit, then maybe one got used to it.” In this line, the reader understands so much about the duality of religion and queerness.

Some essays are less literal. Suzanne Lee’s “The Approximate Weight of Truth” offers a metaphorical approach to coming out. She refers to her sexuality as “the dream-stone that slept inside my mouth at night” which is “as bitter as shame and twice as sharp,” transforming the coming out process into an event both dreamlike and inevitable.

Crooked Letter i weaves in stories that fit the expected southern narrative of conservatism, ones that deserve our attention and a change in atmosphere, as well as acknowledging that this social climate no longer exists universally throughout the South. There are instances in this collection of a world where queerness no longer feels like the antithesis of southerness. In Stephanie Woolley-Larrea’s “Straight as Florida’s Turnpike,” she addresses similar feelings, noting, “There were movies about us at the theater and shows about us on television. We were lucky.”

Still, stories of real vitriol and hatred must be told, heard, and acknowledged. Merril Mushroom’s “The Gay Kids and the Johns Committee” shows the persecution and absolute terrorizing of the queer community that existed in the 1950s, when “citizens were arrested” and newspapers were “publishing lists with names, addresses, telephone numbers, and places of employment.” This essay shows not only where we’ve been, but how recently we’ve been there. Susan Benton’s “The Other Side of the Net” reveals how this hatred still manifests itself today, when her sorority “wanted [her] to resign from the sorority on moral charges” after discovering that she was gay. These voices must be pushed forward to remind us that not everyone is safe; voices are still silenced, people are still hiding.

Not all of the essays are as effective. Thom Koch’s “Late News,” for example, felt distanced, as though the author was obligated to relay the details rather than wanting to relay the details. Lines like “I suspect having someone living with me might change the attitudes of some of my friends and even family” make this story feel less unique and individualized. This essay did not seriously detract from the overwhelming affirmation and honesty that this collection offers, but it does create a slight setback in moving through the narratives.

While the book acknowledges its own shortcomings—including only two stories by people of color, and no stories from anyone who identifies as bisexual—this lack of representation is disappointing when trying to construct a multifaceted narrative of southern queerness. Voices of color are already on the margins and bisexual erasure is extremely prevalent; in a collection that truly wants to empower the voiceless, these voices need the most space. The exclusion here does not feel intentional, especially considering that the editor acknowledged where the collection falls short. Creating an anthology means that some voices will be left out due to limited space and sometimes limited range. Still, the book must also be held accountable for seeking out the voices that have been silenced the most. That said, this book still provides a much-needed look at the landscape because so often queer southern stories are silenced, overlooked, and misrepresented.

This book is important because there aren’t enough like it. For decades southerness and queerness have been viewed as insoluble. This book attempts to coalesce these into a solid identity that people can own without trying to negotiate part of themselves in order to appease another. I have been fortunate that my southerness has been cultivated in a community that long ago normalized the other, the queer. New Orleans is hardly the South when looking at political landscape and tendencies in voting, especially in terms of social ideology. I’ve always recognized that many of those who share my southern, queer identity are not as fortunate as me to come out into an unflinching pool of acceptance. But this does not make my story any less relevant or valid, as this book has showed me.

Marisa Clogher was born and raised in New Orleans, Louisiana, and is currently enrolled as an undergraduate at Loyola University New Orleans.