|

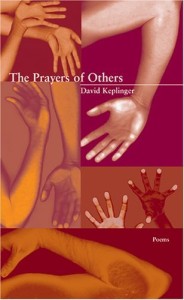

MILTON, BLIND and useless, visited the office of employment in Malebolge. He’d had it with paradise, this sitting around doing nothing to the tunes of Petrarch. There is no devil as we’ve come to think. In the offices and offices of clerks, each desk job has a stamp that snuffs the paperwork of one door down. (from The Prayers of Others, New Issues Press, 2006) |

|

ENORMOUS YELLOW SKY |

|

(from The Most Natural Thing, New Issues Press, 2013) |

|

TRAVELING |

|

(from an unpublished manuscript) |

INTERVIEWER

I am enjoying your collection of poems The Prayers of Others, especially the line: “There is no devil as we’ve come to think.” What is the devil then, do you think?

KEPLINGER

When I wrote that line I was thinking about the one devil, the one image which was the embodiment of evil, chewing on Judas in the basement of hell, who comes to rain terror over the lives of the good and who comes to bear out punishment on the lives of the not so good. I was thinking of the devil on one shoulder and the angel on the other. In contrast to that is the image of Dionysus, one of chaos, drunkenness, comedy, change. The Greeks embraced unpredictability; they equally embraced the illusion of a separate self who served in the world, embodied in the image of Apollo. They saw no need to put these forces at odds, necessarily. Keats sees equal beauty in autumn’s decay (“thou hast thy music, too”) as in the songs of spring. Yet I grew up Catholic; I have a little vestige of the Old World in my thinking, too. Long story short, I don’t know what the devil is, and I don’t want to know.

INTERVIEWER

“It is not a given,” the poem goes on, “that the heart is lonely and so must live forever.” What is a given?

KEPLINGER

Nothing is given. Nothing is certain; even Newton’s physics break down at the subatomic level. Nothing is promised from my human perspective. From my animal perspective, I think everything is given – everything is still here, right now, good for the taking, given, a gift.

INTERVIEWER

In “There is the Woman,” you write that she “was a beauty once, but now has lost her beauty.” Time’s ravage is often marked for women by the loss of beauty. Is there an equivalent time-marking mourning by men?

KEPLINGER

I prefer not to gender loss, so as to say, men experience aging in this way; women in this way. I’m 44, and I feel a general mournfulness at the loss of power in my body, how my body is slowing gradually towards a stop. I’m not kidding, though, when I say that the closer I get to silence the more I hear the source of something huge of which I’m a part. We have bodies; our bodies are supposed to keep our brain functioning and keep our personalities alive. The function of the body is to keep foreign bodies out. There’s so much violence going on in my body right now, in order to keep my personality alive. And, somehow, I suspect, there’s violence going on in the realm of the mind, trying to focus, narrow the personality, identify me as a poet, a teacher, a man, a human, etc. To keep it safe. Our bodies are like acrobats on the high wire doing this amazing thing while simultaneously digesting food and pumping the heart and producing new cells. The body is so engaged in the work I might even believe that that’s all I am. The closer I get to the loss of that beauty, the closer I get to real beauty, which is the source of all that energy and intelligence, whatever that is. But I believe it’s what Whitman was describing in “Song of Myself.” In that poem he invites everything in, so there’s no distinction any more between his little self and his bigness, the whole world. He wrote that on the cusp of middle age.

INTERVIEWER

Is there a particular poem in which you invite “everything in,” like Whitman, or at least more so than in others? If so, can you describe that process?

KEPLINGER

In terms of inviting the outside world in, or, rather, in terms of there being no distinction between the interior landscape and the outside, I’d say I’m trying to capture some of that in my new collection The Most Natural Thing. It applies what I know about Tantrism, which speaks of the whole universe as a body, of which the individual is only a part. The image of the body, its apparently separate parts working in and out of accord with each other but contained within the whole, becomes metaphor for the entirety of existence. In Tantrism (and, thematically, the poems, I’d hope) we undergo an erotic union with everything else, all the time. I found that the more I wrote about the parts of my own body (in the book it’s a man’s body, mine, that’s being mapped), the more I encountered a myth world; I couldn’t merely focus on the anatomy of the object, though I often began there. I could start by writing about my big toe and end with the image of a carnival mask. Or I could write about the pancreas and come upon the image of a curative leech, curled in a preserves jar. I was continuously reminded of the work my body is doing, right now, without my being aware, and yet all of this communication is supposedly originating from a consciousness in me that was not limited to (and is probably separate from) the personality. While my liver and my kidneys seem to hear from this consciousness all the time, I am privy to its wisdom mostly in dreams. I’ve always been drawn to poets of the symbolist order like Max Jacob or Rimbaud or in the shadow boxes of Joseph Cornell. While surrealism seems to want to connect the chaos of dreams with some kind of hidden agenda which gets linked to the personality, the symbolist stuff isn’t interested in meanings at all. They’re just generally wowed by what is, by the correspondences that begin to inspire in the observer a weird, mythic awareness about reality, how strange and impossible and profoundly bigger than imaginable (literally) the is is.

INTERVIEWER

Mary Rose O’Reilley says, “To grow in compassion for one’s own life is the great task of the middle years.” What would you consider the task of the middle years to be, and how does it enter into your current project?

KEPLINGER

I consider the task of the middle years to be the same task as at any other time: to learn to serve others while serving, somehow, yourself, your own calling. That can be complicated for a poet whose work runs the risk of self-centeredness. The task of the middle years is still compassion, but it’s got to begin to turn outward so that the self we begin to see is something larger than our poems, our reputation, our job, or our relationships. It’s absolutely necessary. A great poet, and a brother to me, the late Jake Adam York, taught me that to fully engage with the work I can’t spend all of my time contemplating Being. As Milosz puts it, sometimes you’re cornered by History. The work must grow to fit this larger sense of self. Or the fire will go out.

INTERVIEWER

What definition would you hazard for the prose poem?

KEPLINGER

It starts in the middle and ends in the middle. It’s simultaneously vertical and horizontal, narrative and lyrical. You could also say that a prose poem takes itself less seriously; it knows how inconspicuous it seems—no lines, no insinuation of form. So it’s got to be smarter, wittier, cleverer. The nutty professor in chucks and jeans. Forget the form; I’m not anything; I’m not a poem, the prose poem says. And then it gets under your skin.

INTERVIEWER

The image of yours I consider most affecting is that of hunting mushrooms under a yellow sky in “Enormous Yellow Sky,” from your most recent collection, The Most Natural Thing. In it, the speaker springs not like Athena from the forehead of Zeus but from his own toenail. Are poets a self-propagating species, as capable of reseeding themselves as the Egyptian walking onion?

KEPLINGER

That’s a lovely reading of the image which I’d never considered. The image comes from an old Czech saying told to children. One of my students in Ostrava once shared this with me. When children ask where they lived before birth, their parents answer, “hunting for mushrooms.” Decent poets, even great poets, need everyone else, like children need their parents to be born. The story is nice, too, though.

INTERVIEWER

Whose life or what life would you live if you could/had to choose another’s?

KEPLINGER

As I mull over this question, I realize there’s no one. If I chose someone above my station, I’m afraid I’d not be evolved enough to appreciate what I’ve got. I’d end up being myself all over again.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a fallback joke you tell in certain situations?

KEPLINGER

I am a terrible joke teller and most of the times when I try to be funny, I’ll make people sad. And vice versa.

INTERVIEWER

Do you ever use humor as a tool or mechanism?

KEPLINGER

The well-delivered punch line is a noble teacher for poets. I have a friend who does stand up and has been very successful. When I watch him I see this magical thing take place: the joke brings us to this precipice, this strange, surprising place, but at the same time we find ourselves in the most intimate, familiar of realms. We laugh because what seems so strange is simultaneously so familiar. Once more, that’s the function of the Dionysian power. To write something hilarious is to bring the reader to the edge of oblivion, but not quite over. We come back from oblivion whole again. We live a resurrection story. Comedy teaches that no matter how you try to fuck things up, the world has a way of aligning itself, and gets well, ends well.

INTERVIEWER

I love that idea that “We live a resurrection story.” It’s especially interesting to me considering what might have implied a crucifixion or phoenix-rising in earlier centuries is as likely in the 21st to conjure zombies. How will your next project reflect your ongoing transformation?

KEPLINGER

My next project, which is a book of poetry in lines, is still figuring out what it wants to say. I’ve also produced an album and begun a lecture tour in which I sing the poetry of my great-great grandfather, a collaboration with the dead, if you will. He was a soldier falsely accused of desertion and taken to Forest Hall Military Prison and then Stone General Hospital over an eight month period in 1863-1864. I can’t help imagining he was nursed by Whitman, who visited the hospital at that time. With the album I am finishing a book of poems that explores those crucial months. This, too, is a kind of resurrection. He would have been forgotten; but over a period of years I have put together a day-to-day account of some of the most horrific and some of the most beautiful moments of his life. Whether we remember him or not, I’ve come to learn, he existed. So much exists right before our eyes and yet we fail to notice it, my poetry continues to teach me. My work has been my way of trying to open my eyes.

Interview conducted by Amy Wright, Nonfiction Editor of Zone 3 Press and Zone 3 journal, as well as the author of three chapbooks—Farm, There Are No New Ways To Kill A Man, and The Garden Will Give You A Fat Lip.