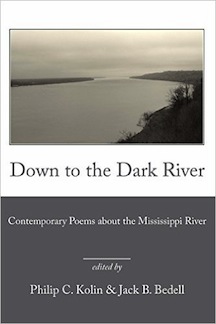

Down to the Dark River: Contemporary Poems about the Mississippi River, edited by Philip C. Kolin and Jack B. Bedell. Louisiana Literature Press, 2015. $18, 232 pages.

Growing up in central Mississippi, I was far enough removed from the river that serves as muse for the 100 poets in Philip C. Kolin and Jack B. Bedell’s anthology Down to the Dark River: Contemporary Poems about the Mississippi River that it remained more of an abstraction than a physical reality for most of my childhood. In elementary school, we learned that the river for which our fair state was named was “The Father of Waters,” that its physical length and contours curved and extended in similar fashion to its long, curvy name. Since “Mississippi” was staple of spelling tests year in and year out, I learned to spell the word I loved hearing politicians and grandfathers say this way: “M-I-crooked letter-crooked letter-I-crooked letter-crooked letter-I-hump back-hump back-I.” When I looked at a map, I tried to imagine the river’s currents spelling the crooked letters and hump backs in a muddy cursive. On trips to New Orleans, I crossed over the river many times but never considered it for any appreciable time until a late elementary school field trip to Vicksburg’s Civil War Memorial park. There, I learned of the river’s strategic role in the Union’s 1863 siege of the town and its equally important role in the state’s nascent gaming industry—a hoped for economic boon—in the 1990s.

Though we who hail from club Mississippi assert a special claim to our namesake river, reading this anthology with perspectives as diverse as the landscapes and cultures the river touches, reminds the reader that no one owns the natural and spiritual wonder. A river so vast inspires diverse interpretations. Its text is liquid and Protean; thus, it can accommodate wildly different perspectives in its Whitman-esque, American embrace.

The editors include Langston Hughes’s “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” as the prologue to the anthology, which begins with the famous line, “I’ve known rivers.” In an anthology—which aims to be welcoming—this line is important: It brings up the idea of knowing, of epistemology. What I realized from reading the work of 100 different poets is that knowing something as grand as the Mississippi River is wholly based on who you are, when you are, where you are, and what you need. In that poem that speaks of rivers generally, Hughes positions the Mississippi alongside the Euphrates, Congo, and Nile—famous cradles of civilization—but devotes more space (3 lines as opposed to 1 for the others) to the cradle of his American civilization. Hughes argues, and the editors and poets in Down to the Dark River concur, that the Mississippi River is not only a geographic and economic force but also a poetic muse that demands contemplation and responsive creation.

In the introduction, the editors point out that “the Mississippi has shaped the course of American history,” and the voices that sing also attest to the river’s shaping personal histories. Similarly, the poems chart the changes—historical, spiritual, and ecological—of the people and landscape “from evolution to pollution.” In such sweeping anthology with diverse choir of voices from Natasha Trethewey, Virgil Suárez, and Sheryl St. Germain to Carl Phillips, Sterling Plumpp, and Frank X Walker, no single type of poem—form, diction, or aim—can encapsulate the Mississippi. This anthology pays tribute to the histories (ranging from personal to collective), cultures (from Native American tribes to European explorers), voices (from lyric to narrative), and landscapes (from Michigan to Louisiana, Great Lakes to Gulf of Mexico) touched or influenced by this natural wonder. While many poems associate the river with music, others associate the river with the human tragedy of slavery or the natural terror of Hurricane Katrina. The text of the river—for any reader—is complicated and cannot be reduced to a universal, but is best known in the poet’s specific language just as the poet best renders complex ideas like love and grief in couture language.

There’s a nice circularity to this anthology—even in its diversity. The last line of Hughes’s poem reads, “My soul has grown deep like the rivers,” and thus he connects the great Father of Waters to some essence of being. In the last poem, “Confluence of the Two Rivers,” Jianqing Zheng mixes a cocktail of the Yangtze and Mississippi rivers. The final stanza gives a command to the reader:

Sip slowly.

You’ll hear the sound of

confluence,

sweet and mint,

seeping deep into

your soul.

A poet’s considerations of the river lead him to the soul, as well as to the idea of confluence, or “flowing together.” That’s what a strong anthology such as this one does—allows many voices, many perspectives to flow together regardless of the harmony or dissonance. Just as the Mississippi’s waters are far from pellucid—from mouth to delta, from crooked letter to hump back—the mud and darkness allow for mystery, as does the scale and movement of the river.

Douglas Ray is author of He Will Laugh, a collection of poems, and editor of The Queer South: LGBTQ Writers on the American South, an anthology of essays and poems that was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award. He received his MFA from The University of Mississippi and is Poet-in-Residence at Indian Springs School, a boarding and day school in Birmingham, Alabama. He joins the faculty of Western Reserve Academy in fall 2016. Find out more at sdouglasray.wordpress.com.