I grew up in Tehran, where Farsi is used everywhere. It’s also my mother tongue. I scored high in the Farsi literature section of Iran’s competitive national university entrance exam. I think Farsi sounds as pretty as French. If more evidence is needed, it was a bunch of drunk Cajun guys in New Orleans who told me the same thing. Moreover, Farsi is an outstanding language that, somehow, broke through the monopoly of Arabic in Muslim nations to dominate numerous royal courts throughout centuries, continents, and cultures. If that is not enough, it is also written in a cursive flow. It is pretty to look at. Frankly, it is hard to think of a better medium than Farsi to write about life; just ask Rumi, Hafiz, or Goethe. That is probably why, after more than four decades of incompetent, ruthless, and truculent Ayatollahs doing everything they can to undermine and damage the Iranian arts and our cultural diversity, there are still more than 30 centers of Iranian studies and Farsi around the world, without any financial support from Tehran. That is no small feat in a world of never-ending budget cuts.

Sometimes I miss the patterns, shapes, and marvelous shades of green and blue that could take me to some brilliant peaks of Farsi’s genius without a word uttered. On those occasions I am lucky to be able to visit my favorite museum in the city, the Asian Art Museum. It has a small room of ancient artifacts found on the Iranian plateau. I still remember the fuzzy, joyful feelings I experienced entering this room of ceramics, metalwork, and jewelry for the first time. A feeling of familiarity and sadness.

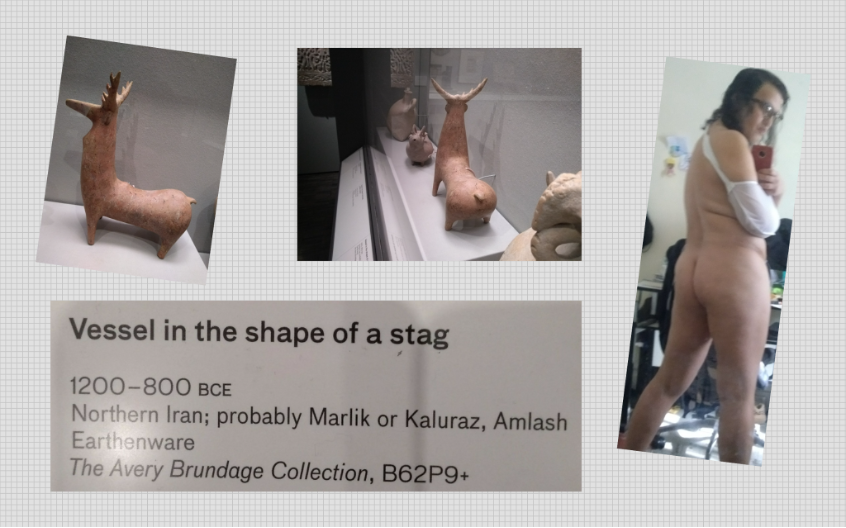

Actually, one of my go-to grounding techniques involves one of this room’s artifacts, a terracotta sculpture of a stag that was made 1000 years before Christ. I mentally trace its perfect booty curves in my mind’s eye to ground myself. And it works half the time. Yes, I like booties. Almost daily, I go stand at the center of my dingy room to look at my booty’s reflection in the mirror. I judge my booty. Sometimes I touch it gently. Mostly, I want it to resemble that vibrant, millennia-old stag’s booty. At this point in my life, that is my true connection to my Iranian heritage; it ain’t Farsi.

Figure.1: An image of the author’s tired booty is provided on the right side in comparison with the timeless beauty of the millenia-old stag’s booty @ the Asian Arts Museum of San Francisco.

I cannot express myself freely in Farsi. I cannot even stand hearing myself in Farsi. Every verb, adjective, adverb, preposition, idiom, conjunction, and sound in Farsi has witnessed my humiliation. Why should I ever use those terms and sounds again of my own free will? Why must I care about a language in which I have no way to identify as a boi? This tragic state has often meant that when I am in Farsi, it is mostly muscle memory and not much creative thinking, joy, or passion. I have always found the Farsi language inefficient and weird, whenever I needed it most. Examples are abundant: How do you avoid melting into the ground when using Farsi to introduce your first boyfriend to your closest friend and gasping at his homophobic reaction? What Farsi terms are appropriate or comprehensible to Iranian laypeople to use in a chat with family members when speaking about sexual orientation, gender expression, or being a non-binary person that may not require hours of charged explanations? How can one avoid triggering heart attacks upon breaking the news of getting an orchiectomy to family? How does one deal with attempts to force one to return to the closet every time one makes a phone call to a relative? In Farsi I cannot express or save myself.

On the other hand, the English language is my rock, playground, and dungeon. In it, I feel confident and safe. I can be my unmitigated self in English. I can identify as faggot, dyke, boi, queen, or whatever the hell I want to. I have realized I am more respectful in English. Occasionally, it feels as if I am a kinder person. This could be due to my learning about consent for the first time in English. Whenever I have such thoughts, I immediately censor myself, followed by a 2-minute mindfulness grounding routine to steady my head. I think of that ancient booty.

After my death, I want to be immortalized in someone else’s grounding technique.

When I was 14, I began to take English language classes in Tehran. My mother, whom I haven’t spoken to in years, suggested I enroll in a nearby language school. The school was only a few blocks away from our apartment. Each term lasted one month. The classes were hour-long sessions, five days of the week. Students were banned from speaking in Farsi. My classmates were not teenagers. They were a mix of college graduates, adjunct professors, mid-level professionals, and occasionally stay-at-home sons, retirees, or business owners. I went to those classes until I was 18 years old, and there were no more advanced levels to take.

Here, in San Francisco, in my room, I don’t have any books in Farsi, any Iranian artwork, or even images of an Iranian person, except for some old passport pictures from when I used to be a man, resting at the bottom of a box of documents under my bed. Further, I don’t remember the last time I spoke in Farsi with a friend or family member. I have mostly avoided contact with Iranians. I was not always like this. I have an expansive personality and a desire to have a hot booty. But I have had to curtail my exposure to people, in particular Iranians, after coming out as trans. I have lost loved ones as a direct result. And why not?! The Farsi world has been specially hostile to Iranian queer people for more than a century.

Today, I’m cooped up in my room, reveling in the fact that I successfully negotiated an hourly wage increase for a temp job from $30 to $100. If that job negotiation were in Farsi, I wouldn’t have bothered negotiating. In Iran, I forced myself to excel in Farsi and get high grades. Sometimes I do certain things for years and years because I want to survive. It seems most Iranians are intimately familiar with these thoughts. The world now knows that millions of Iranian girls and women strongly despised having been forced to cover their hair by the Islamic regime.

Iranians are so angry they’ve taken to the streets for the past several months. Sisters, daughters, grandmothers, middle schoolers, high schoolers, art students, nurses, seasoned accountants, hopeless retirees, cocky chess players, sexy rock climbers, energetic lawyers, everyone. At the beginning of the protests, an ocean and three continents away, on Ohlone land, I went on the Internet to read their news. At first, I was only following the BBC Persian website to keep myself updated. Then I decided to dive into Twitter to get the most accurate information directly from Iranian people. The following are the three most important things I learned:

- “Woman, Life, Freedom,” the defining slogan of these protests, is a touching and deeply meaningful Kurdish slogan (Jin, Jîyan, Azadî, ژن، ژیان، ئازادی) that was loudly heard in Saqez — the first city that protested the murder of their daughter, their neighbor, their friend, Jina “Mahsa” Amini. She had gone to Tehran to visit her brother and was violently accosted and detained by the brutal morality police, falling into a coma shortly after. She died of her brain injuries. She had aspirations to become a lawyer and was about to begin college in a month. She was 22 years old.

- Sadly, I could not find any Farsi Twitter accounts that promote having a hot booty. This could be an interesting area of future activism for me.

- There are a ton of Iranian queer and trans people of varying political preferences and degrees of distance from the closet. I have come across Iranian trans and queer people around the world who are senior engineers, Ph.D. candidates, political activists, college students, and software engineers. I am so proud of each one of them, including the ones who have blocked me or whom I have blocked.

The group of Iranian queers that I follow has a frequent Twitter campaign using the Farsi translation of #I_am_queer. I participated in one campaign with the most depressing tweets. Shortly afterwards, I was almost puking in response to publicly sharing my most traumatic thoughts and memories. I could imagine the endless pity that whoever read my tweets might feel toward me. I was disgusted. I did not want pity from Iranians. Fuck them. Then I read tweets by other participants. They were simple greetings and queer friend requests. It was touching and sobering. Some queer people in Iran never experience having one accepting face in their lives.

My initial connection to other queers was also through the Internet via various classified sections of the early aughts — Yahoo.com, Excite.com, and some other sites that are probably extinct now. One early memory was learning Becky was short for Rebecca during a random chat in a penpal forum. My “teacher” was a fellow 15-year-old from Amsterdam. She and her whole family were atheists, which was fascinating for me, since I was immersed in the Islamic regime’s propaganda. When I told Becky that I enjoyed wearing women’s clothing, she called me a cross-dresser. I immediately loved that word. Cross-dressing, as in I had a ton of dresses (even though I had none), and my superpower was changing my dress in a blink of an eye. I was comically wrong. But I still like that term and identify as a crossdresser. My reason is less about queer politics and more about the booty vibrancy of this particular slice of the populace.

Another early correspondence was with an older white gay man from Jacksonville, Florida. Patrick was 22 years old, tall, versatile and a bottom. In my first message, I complimented him on his pretty blue eyes. I was 17 years old and had never complimented a man in that way. These days the internet is still how queer people in Iran get to express themselves or (virtually) exist. I have always loved the internet. The Internet’s language is not Farsi. Is that why I love it? No. I love the internet because it is extremely helpful in finding really high-quality booties.

So far this essay has been expounding about a certain relationship between the Farsi language and a living queer person, myself. Now, it would have been nice to cover this relationship in the afterlife as well. But I cannot stand the thought of being dead. It is a big fear that is pushing me to save up enough money to have a terracotta sculpture of my booty made and buried in a good location for future excavations and cultural critique by people who don’t know my language, my fears, or my life. All they would know of me will be perfectly handcrafted booty curves signifying my existence.

Nina Ruth Mir (they/them) is an Iranian person. They love riding their bicycle, doing nothing, cooking, daydreaming, and meeting weird people. They are currently living in San Francisco, CA, where they like the weather. They enjoy writing short stories, essays and making art out of discarded stuff.