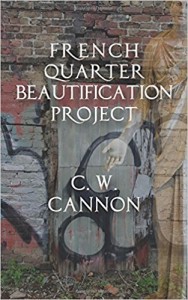

French Quarter Beautification Project, by C. W. Cannon. Lavender Ink, 2016. 244 pages, $17.

With his latest novel, French Quarter Beautification Project, C.W. Cannon unleashes an outrageous tour de force that situates him squarely in the pantheon of New Orleans writers, those poor souls struck by the city’s muse, compelled to try to capture its glorious insanity in literary prose.

The cover, designed by Bill Lavender, features a graffiti-marked, cracked wooden door set within a crumbling brick wall. A ghostly image of a tunic-clad woman with outreached hand hangs on the side, a small face emblazoned on her sash. On the title page, the subtitle “a melodrama” appears under the title. The dedication is to “my co-workers” at a handful of French Quarter establishments. Next is an epigraph from Baron Ludwig Von Reizenstein’s 1854 gothic romance novel, The Mysteries of New Orleans, about common sense rebelling against the mysterious, and extraordinary events leading to the improbable becoming true.

Thus begins our journey with a first-person narrator, in fedora and carrying a whip, walking through the French Quarter of New Orleans, circa 1986, on his way to work. The landscape is described as in disarray, a space in transition, an opening image of the neighborhood’s famed black iron balconies giving way to construction beneath and scarce inhabitants behind. On his way the narrator ponders a “protagonist” called Buck, possibly of a book he’s working on, possibly an alter-ego, possibly just the narrator’s nickname. At any rate, Buck is a composer (“Yes, of music. How charmingly arcane!”), and that he’s called Buck Rogers because of a tendency to drift in the inner-space of his own thoughts, a space filled with classical music that sometimes, but not always, actually enters Buck’s head through earphones (“a Barber Essay or some other schlock”).

Comedic tension is derived from the first-person narrator repeatedly coaxing Buck back to reality from frequent flights of fancy. He addresses his creation directly: “Good boy, Buck!” Cannon ingeniously wields this delightful conceit: a narrator, in character to work a job, conversing with his “protagonist,” who is also in character wearing a fedora. The point-of-view whips dizzyingly between first, third, and sometimes second person. But the effect is gratifying, once the reader’s strapped in for the ride. Thus we move through Buck’s mind as he tries to sort out his idiosyncratic worldview, while he’s constantly interrupted by events in reality, such as other people on the street: “a trio of black teenagers . . . they’ll fuck with you when you walk by. Why? Give me a second, I’ll think up a reason.”

Buck arrives at work, a restaurant called Everybody’s Happy (“a tourist trap with no tourists in it,” a “shithole where you serve assholes” and what the employees call “Nobody’s Here, a more descriptive term”) and is whooshed off the street and into the place by a blast of air conditioning, the same air blast that will accompany his exit at the end of the shift. Everybody’s Happy is a wonderfully psychedelicized place, inhabited by costumed waitstaff characters such as Tinkerbell, Sheriff Cobb, a barefooted Inmate 50667, who’s supposed to be acting manager but spends his time smoking blunts with the staff in a cement bunker and selling weed and coke in the dressing room, Sludge the Lion, whose bare ass shows through a threadbare costume, and who peppers the back-of-house scene with occasional saxophone solos. The waiters engage in sexual flirtation, of the hetero and bisexual variety, morphing possibly at times into actual sex acts with each other and with customers.

Buck works his patrons, “white-flight suburb types,” for tips, and gropes, as he wears his fedora and cracks a whip, half-assed in character as Louisiana Jones. But as he does so, he can’t stay out of his own head, or doesn’t want to, his outer-space, defined by masterful knowledge of classical music, which he imagines as gloriously over-the-top metaphors for his own detached state of being: such as Gesualdo, “Prince of Venosa,” murdering his wife on the cathedral steps.

The restaurant is defined by its ridiculousness. The faded fanciness of worn red velvet is compounded by the stupidity inherent in individually themed tables. The customers are a loathsome bunch, not tourists, who would never go there, not locals, who never did go there, but the only group left: yokels, quasi-tourists visiting from the ‘burbs, who never tip. Ownership is clueless and callous, appearing in the form of a Mr. Polpetta, who storms off the street and through the restaurant, insulting the staff, threatening to fire people, wondering what the hell is wrong with the place and with himself for investing in it. That leaves the staff, comprised of the split-personality narrator and his cohort, whose only ostensible purpose is to punch a clock and draw a paycheck, but who also seem drawn to the place, and to each other, for some other, unnamable reason.

During the shift Buck is visited by a woman who is trying to find him, Augusta, a girlfriend from long ago, who is a gifted pianist and has the ability to imagine life through intimate knowledge of the chords of classical music. But she’s told that Buck’s not there, and her pursuit of him continues through the French Quarter, after Buck’s shift ends. Buck and his various coworkers move through a series of drinking establishments whose names form the novel’s chapters: The Bourbon Oasis, The House of Bonaparte, Rancho Pillow. The stops along this surreal bar-hop are punctuated by brief Intermezzos on well-known French Quarter streets, each one providing details about the backgrounds of Buck and Augusta. Something is wrong with Buck, even beyond the obvious, and neither the reader nor Buck can identify what.

The plots gets violent after a stop at The House of Bonaparte, where a glass-eyed, hard-nosed character named Jules converses with Buck. Jules is Buck’s daddy, which may or may not mean that he’s his biological father. In the bizarre-o, drug-and-booze-lubed world spun by the narrator, nothing is certain. Buck wants to obtain a gun, possibly for protection against a hammer murderer who’s been terrorizing the gay scene in the Quarter.

The next stop is Rancho Pillow, which features another in a string of delightfully drawn bartenders, their single unifying characteristic being their near-complete loathing of their clientele, “near” because their fellow service workers are cut some slack. Also everybody has slept with everybody else, or wants to, in this Quarter service scene. Although Buck isn’t sure what he wants, or what the hell is wrong with him, it’s clear he’s fucked some of his co-workers, and wants to again. What’s more, they want him, too—he’s pretty—only he can’t decide which way to go, if he wants a male or female lover.

The first-person narrator, it turns out, is some kind of deity or angel who is charged with helping Buck in his quest. In a long prose-poem section, the deity floridly muses on his role, which he likens to what “the Jews call . . . Beschert,” which means bestowed or given, and the deity’s feelings for classical music overlap completely with Buck’s. They are one and the same. All emotion and indeed the entire realm of human experience is echoed by, supported by, derived from, the works of Mahler, Bach, Brahms, Beethoven, Chopin, Wagner, Webern, Crumb, Messiaen, and others. Buck turns to the composers for purposes of expression, and the deity is there to help set Buck right, “to rend and reconstitute” himself. Augusta plays a key role. As a product of uptown New Orleans, she’s trained in piano, but her gifts surpass any prep school training. Her quest to play piano for Buck is tied to Buck’s fate.

The journey ends back at Everybody’s Happy, where a meeting of a homophobic cabal comprised of Jules, Polpetta, and others is interrupted by Buck. The other waitstaff arrive as well, as does Augusta, who takes to the piano. When Augusta begins to play, the music becomes tangible for everyone, driving the action, or the emotion of the action, for all of the characters, including Buck. Buck’s fate, along with Augusta’s, unfolds in a chaotic penultimate scene, as the remaining characters are dealt with as well. The world of the novel is hermetically sealed in this way, which is among its strengths. As is the incredible musical knowledge on display, which moves from classical to jazz in a later scene, suggesting a whole other book that could have been, or could still be.

Cannon’s novel touches on many literary flashpoints on its winding course: the trippiness of William S. Burroghs and Hunter Thompson; the edginess of Jim Thompson or James Ellroy; the weird love of Larry Brown and Carson McCullers; hints of Ulysses, The Satanic Verses, and The Master and Margarita as well. Always, New Orleans as an imagined space is at the center of the book, and so other New Orleans tales come to mind. But Cannon situates his world just outside the known literary tapestry of the city. Cannon’s French Quarter is neither the current Tropical-Isle-and-antiques-shops version that we know today, nor is it the fabled and false Marie-Laveau-and-quadroon-balls lore. It’s another, a unique and torn-up place, stuck in a delicious mid-eighties purgatory, between eras, yet inhabited as always by those inebriated and otherwise gone souls who can’t figure out what they’re doing there and couldn’t possibly exist anywhere else.

Jeremy Tuman teaches English at Xavier University of Louisiana. His writing has appeared in The Rumpus, The Journal of College Writing, and Xavier Review. Jeremy plays guitar in roots-rock band Bob & The Thunder and is supported in all pursuits by his wife, their two young boys, and two brown dogs.