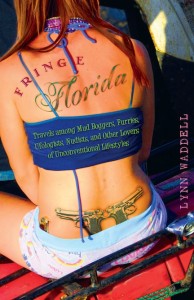

Fringe Florida: Travels among Mud Boggers, Furries, Ufologists, Nudists, and Other Lovers of Unconventional Lifestyles, by Lynn Waddell. University Press of Florida, 2013. $24.95, 255 pages.

When most people think of Florida, they think of retirement, yachting, and college students on spring break shot-gunning beers. Many of us never get to see the swinger clubs, fetish dungeons, biker rallies, and coleslaw wrestling matches that are, according to Lynn Waddell, just below Florida’s sunny surface. From exotic pet owners to nudists and sadists, these members of alternative lifestyles are often hidden in plain sight within what many may believe to be an average community.

Waddell, a Florida transplant, is a freelance writer whose work has been featured in a variety of outlets including Newsweek, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, Christian Science Monitor, and Budget Travel. Her recent book, Fringe Florida: Travels among Mud Boggers, Furries, Ufologists, Nudists, and Other Lovers of Unconventional Lifestyles, is a report on a number of unconventional lifestyles and subcultures. These include: exotic animal lovers, strip club owners, female motorcycle club members, members of various spiritual groups, alien enthusiasts, swingers, and many others. (Hints of her experience as a travel guide writer appear in certain areas—e.g., factoids about the exotic animals owned by Floridians, or the marked history of a biker gang).

While Waddell paints an accurate picture of the friction between the fringe groups and the rest of society, she also describes the way that marginalized groups have changed over time and have contributed to their city’s development, income, and local culture. She offers us a more complicated view of people which most of us are blinded to, preferring, whether out of convenience or indolence, to focus on a particular “label” or stereotype. For example, Joe Redner, owner of the third most popular strip club in the world and the “father of the lap dance,” has financed a city park, donated to numerous charities, and even run for local office. Some have simply written off Redner as a pervert or sex merchant. But that belies his activities as a reformer, leading important social movements in the Tampa area in defense of the First Amendment as well as in support of LGBT rights.

Each chapter of Fringe Florida provides such a window into the life of an allegedly subcultural group. To cite another example, there is the fetish-player couple Tim “Ponygroom,” who serves as master, and “Ponygirl” Lyndsey, who serves as his horse. The couple may role-play, but they are also politically active in their community, and successful in their professional lives. Tim engineers devices for paratroopers, and Lyndsey is a trained opera singer and has taught for more than twenty-five years.

Waldell also often returns to the idea that much of Florida’s population (over half) consists of transplants. She takes a clinical approach in examining her “Fla-zoons” (named after neozoon, meaning introduced species) and their broad range of lifestyles, and her findings in the fringe world display respect for it as well as transparency; she is a self-admitted outsider looking in. By the end of the book, one may justifiably conclude that “fringe Florida” may not be that fringe after all.