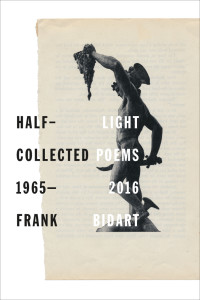

Half-Light: Collected Poems 1965-2016, by Frank Bidart. FSG, 2017. $35, 736 pages.

I wonder how many readers, upon first glancing at the cover of this magnificent doorstopper, misread the first part of the title of Bidart’s career-spanning volume, Half-Light, as “half-life”? After all the two nouns, “light” and “life,” can work interchangeably in this context. The subtle play on words—and a forced rhyme, perhaps, if only for the eye and not the ear—suggests we’re about to encounter a speaker dwelling in the liminal space between what’s clear and what’s to be uncovered. By dredging up bits and pieces of his biography and weaving them together into multi-layered tapestries of personal history, Bidart reflects on his life with the full understanding that some things might remain forever hidden, in “half-light” as it were.

Frank Bidart has been a fixture on the American poetry scene for over sixty years. A friend and a student of Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop at Harvard, he is a master of the dramatic monologue, although, as Helen Vendler aptly observes, his monologue poems are not narrative in the strict sense but “spliced together, as harrowing bits of speech.” This collection is actually his second retrospective. As he tells us in “Note on the Text” appended to the back of the book, which besides poems includes three interviews with Bidart, in 1990 he published a book—reprinted here—that collected his first three volumes in reverse chronological order. With this new gathering, which is coming out two years shy of his eightieth birthday, Bidart explains his purpose as “not chronology, but a kind of topography of the life we share—in chaos, an inevitable physiognomy.” That many of us can see ourselves in his work, which is often angry, bitter, and guilt-ridden, is both scary and strangely redeeming.

The poet’s insatiable need to satisfy his carnal and sensual hunger leads to the kind of self-examination we usually dub “confessional.” When we read his poems, we become voyeurs who get pulled deeper and deeper into the poet’s personal iconography. Archetypes and mazes proliferate. The search for “a button, lever, latch // that unlocks a secret door that / reveals at last the secrete chambers” begins to seem futile after a hundred or so pages, but the journey is no less exhilarating for that. Indeed, there is not much that’s cathartic in this project; any equanimity experienced by the speaker and his readers is short lived. At the same time, Bidart’s purpose isn’t to be sensational. Rather, he bares it all in order to understand himself and those around him. “Suffering has made me what I am,” the poet announces. Consequently, his psyche and his physical self seem always to be teetering over a precipice—his images and registers shifting endlessly.

Bidart’s suffering stems from his troubled relationship with his parents, especially his mother. This life-long therapy session finds its equivalent, stylistically speaking, in Bidart’s sequences and long poems of various shapes and sizes. Coming at the source of his pain from a variety of angles wouldn’t be as successful if it were done with short poems, which is why, arguably, his life’s work features relatively few stand-alone lyrics. Short poems tend to be too formally contained, while Bidart’s best poems contract and expand continuously, becoming porous at the onslaught of his thoughts, feelings, and emotions. These sequences are like “the River of Time” the poet mentions in one of his early poems: “Dip a finger in it,” he writes, “it comes back / STAINED.” The events of Bidart’s past are the tributaries of his poetic speech that do not run dry eventually but rather get replenished repeatedly in the service of truth seeking.

His poems are “damaged beauties”; their pulse a faint cry for meaning within the ruins of a gay man’s life as well as that of his contemporaries. In “Self-Portrait, 1969,” he writes of a man who “craves another / crash.” In “Golden State,” a key poem from the eponymous 1973 collection, the poet aims to see himself “as a piece of history, having a past / which shapes, and informs, and thus inevitably limits.” Bidart’s early life in California, marked by neglect and abuse, eventually led him to become a New Englander, although the pull of the past, as evidenced by these poems, is a constant force in his life and art. The idea of history as already sorted-and-sieved does the opposite than release the poet from his task: it forces him to go back and rummage through his personal rubble again and again. The idiosyncratic punctuation or the seemingly random use of CAPS, by the way, both suggest that Bidart is a poet who writes without the end in mind.

Although the poet states that he “will not attempt to describe the grief that possessed” him, he does it repeatedly. And, to his credit, he is unashamed to weep in the open. In “Lament for the Makers” he confesses, coolly enough, “What parents leave you / is their lives.” That he’s been able to turn it into art of first order is truly remarkable. Moreover, the personal pain that’s been at the heart of much of Bidart’s early work expands, if not quite gives way, in more recent volumes to a kind of concerned lyricism. In the gorgeous poem entitled “Song,” from the 2008 volume Watching the Spring Festival, the poet declares:

At night inside the light

when history

is systole

diastole

awake I am the moment between.

Bidart, writing himself into time—and history, which, he tells us, “is a series of failed revelations”—embodies the present moment, just like Whitman and Lowell, whose ghosts hover over these poems, did theirs. The world we’re thrown into at birth is a maze indeed, but thanks to Bidart and his poems, whose perennial music soothes and energizes in equal measure, we mortals can more than hope to achieve “eternal safety” before the dimmed lights go out for good.

Piotr Florczyk’s most recent books are East & West, a volume of poems, and two volumes of translations, My People & Other Poems by Wojciech Bonowicz, and Building the Barricade by Anna Świrszczyńska, which won the 2017 Found in Translation Award and the 2017 Harold Morton Landon Translation Award. He lives in Los Angeles.