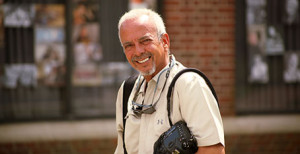

{Editor’s Note: Beloved Loyola photographer Harold Baquet died on June 18, 2015. The following interview was conducted in 2007.}

INTERVIEWER

How did you get into photography?

BAQUET

I was always interested in photographs, and at an early age realized they represented something precious in time and space, how the most important things we owned in the house were family photos. As a boy I had a little toy camera, you know, a little Kodak camera that actually made some pretty good enlargements, and once I got a nice picture of a family member who passed away a year later. The recognition I received as a young boy for that one little picture was kind of inspiring. Years later, I had a swimming coach in high school who had a dark room set up in his office and had made some pictures of us competing and I wanted one, for my girlfriend or something, and he said that if I watched how it was done, if I came in and checked out the process, the printing, so that I’d understand that it took time, then he’d give me one. He was trying to show me, the craftsmanship and the labor that went into something I just gave away without a thought. And it was just magical when I saw that image appear on that blank paper in the development tray for the first time, man, it was something incredible. I was maybe fifteen at the time. Years later, when I got a job and was able to afford some equipment, I bought a decent camera and immediately I wanted to do my own printing.

INTERVIEWER

And how did you learn the actual art of making pictures?

BAQUET

I still question whether my photography should be considered art. I didn’t approach it as art. I mean, I taught myself photography. I have no formal training at all. There’s your liberal arts education: I picked up a book. I spent years in self-exploration and discovery of the processes and techniques that I’m sure that, had I taken a course, I would have figured out in weeks.

INTERVIEWER

What do you mean by self-exploration?

BAQUET

I mean exploring photography and its capabilities—how come what I see doesn’t always translate to what I print? All of these problems were worked out generations before I started playing with my photographs, and it was just a matter of locating the information that I needed in development and seeking an understanding of the processes and techniques, you know, the wrenches, the tools. And I do have a good mechanical sense. I have good sense of space, and the arrangement of space and converting the three dimensions that we live in into that two-dimensional image. I did achieve an intuitive technical understanding of photography, but probably the most valuable tool in my bag is a working understanding of people. That’s my primary subject, the most dynamic and interesting subject that there is. When I first started out in photography, you could just photograph people on the street as they were, but nowadays, you know, you have to stop and ask permission, you have to break the ice, you just can’t photograph a man and his family out anywhere or some intimate situation that you may see in passing. You have to legitimize yourself as a documentary image gatherer; you have to legitimize these people as subject matter, and often times it’s a matter of explaining to people how interesting they are.

INTERVIEWER

Are there racial dimensions to your ability to “legitimize” yourself to your subjects, many of whom are African-American?

BAQUET

Are we going to go there? I mean, that’s always been an issue. Black photographers, both commercially and professionally have worked in New Orleans since the discovery of the first processes. Jules Lyon, a French citizen and free man of color brought the process to New Orleans within a year of Louis Daguerre’s discovery. We had signed groups and portraits by Arthur Bedou, and Marion Porter on the walls of our home. Over the years, white photographers documented our subjects right along side us. Because of that, it opened doors. Just in New Orleans, among my favorite role models photographically were white guys: Johnny Donnell, Jules Cahn, Mike Smith. These guys basically went in there before most of us [contemporary black photographers] were born, before I was born, and they helped legitimize us as subject matter. We’re interesting people!

INTERVIEWER

Was there anything exploitative about white photographers’ use of African-American subjects?

BAQUET

If theirs is the only vision that is allowed to be seen, it would be. Shucks, I only started shooting seriously in the late seventies, and anything before then is out of my hands, man. Thank goodness these guys were out there, sensitive enough to see the value in African- American culture and history and personalities, our social structures and politics, our religious entities. Yeah, it’s different, our food and the rich life that has developed here, especially in South Louisiana, especially in New Orleans. New Orleans, for a black man, was the freest city on the continent before this was the United States. New Orleans had a craft class, we had an artisan class. Jim Crow was really a response to the Americans coming here after the end of the Civil War and realizing that black people were running this city, that Creole was a dominant culture, coming from folks who had descended from free people of color and slaves. The economy was a Creole-driven economy. New Orleans is where the struggle for civil rights began. It didn’t evolve from a power vacuum.

INTERVIEWER

So…

BAQUET

So, this freedom, I mean, it’s always been here, it’s cultural. It brought you Plessy vs. Ferguson, which would bring on the civil rights movement. Our freedom brought you your Jazz. And, yeah, people in New Orleans, we grew up thinking our food was better, our music was better, our climate was better, why would you live anywhere else? I think a lot of our current post-Katrina reconstruction initiative is based on our stubbornness and our willingness to sustain this cross and sustain the pain. And, you know, it’s nothing new. These aren’t the first homes we’ve lost to storm and flood and catastrophe. Our history is filled with rebuilding and reclaiming and reinventing ourselves, and reinventing anyone who encounters us.

INTERVIEWER

Could you talk more about having to get to know your subjects and introducing yourself or gaining permission to photograph them?

BAQUET

It’s a very exciting part of the whole process now. Back when we all did our own black-and-white processing, I found the most exciting part of the process was when you pulled those wet negatives out of the tank and held them up in the light and yes, you know, it worked, it came out, I’m going to be able to feed myself off of this roll of film. And, actually, in many ways that confirming moment really surpassed the excitement of shooting it. We don’t do much darkroom work these days and our digital exposure is confirmed on a little screen at the time of the shot. But the excitement of walking up to a complete stranger is still a great rush. It still seems magic.

INTERVIEWER

Have you ever been turned down?

BAQUET

Very seldom. I’m not making a claim of personal charm or anything but I think it’s the sincerity, my sincerity, that has to come across and self-confidence has to come across…even when you’re scared. It’s part of the job.

INTERVIEWER

I guess this is where I was wondering if there might be any racial dimensions to your relationship with your subjects.

BAQUET

I grew up in an African-American household, in spite of my complexion, I was raised Black. What does that mean? I grew up in a New Orleans Creole home and was raised in the Black Experience. These are my people that I photograph…not strangers. Their struggles are my struggles. I learned at an early age not to judge others by appearances. A great asset to living and photographing in New Orleans is that people know who and what I am, I’m family. It helps to understand the subject. There was a time right after Katrina where I just couldn’t photograph this one man. We were both crying and embracing in this trash heap, knowing that my own family… we have trash heaps all over town just like his…. Yeah, there were very personal moments. And sometimes your access can be almost pornographic in how personal it is and how exposed the person is. There are images I’ll never release, images I hate looking at, that are just painful. And that’s the effectiveness of photography as a medium: the ability to snap you back to a moment, sometimes decades in the past and, for a moment, you’re there, not just there visually, but emotionally, too.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about why you like to photograph in black and white.

BAQUET

The less is more thing. Sometimes the color distracts from the essential subject. Sometimes, just light, line and form is enough, and it allows you to explore the sculptural qualities of that third dimension, that illusional dimension of depth. And it’s fun. I still enjoy the process. It’s a game, even though I don’t print much anymore. I print maybe twice a year, but my printing chops are as tight now as they’ve ever been.

INTERVIEWER

Can you talk more about the types of images or scenes that attract you as a photographer?

BAQUET

The man who’s had the most influence on my career is Keith Calhoun, a local Ninth Ward treasure, and a best friend of mine—I’m his son’s godfather. He and his wife, Chandra McCormick are nationally-recognized documentary photographers. One of the things I realized about what he was doing was that he had a knack for finding things that wouldn’t be around much longer. He helped show me the “document” part of this craft. He had a way of achieving an intimacy with the subject, a closeness that I picked up on.

INTERVIEWER

Is that what you mean by understanding your subject?

BAQUET

No. It’s deeper than that. Basically people are people and we all have buttons that can be pushed, and as a photographer, you have to be able to assess a situation immediately. I remember one Mardi Gras I was coming down Galvez, people were thick along the parade route, and there was a father and infant. The man was tattooed all up, a fierce-looking man in his own right, muscular, strapping, and he was having this wonderful tender moment with his infant son, and I made a few pictures of him and after about the third or fourth picture he looked at me, and all of a sudden his demeanor went from one of parental compassion to fierce, protective defensiveness and I immediately realized I’ve got to square up with this man, which was a matter of acknowledging him as a compassionate father. The sequence of shots went from Teddy Bear to predator in a matter of four or five frames. So, yeah, you have to be perceptive, be aware of the space between you and how you’re coming across. The transformation from stranger to subject happens first in your head.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about growing up in New Orleans and how that inspired your work.

BAQUET

I was born in Charity Hospital, our first house was in Treme, with all that that represents. New Orleans in the late fifties was still segregated in many areas. I mean, I don’t remember the screens on the bus, but I always heard talk of it. My family, we’re all of different complexions. Culturally, we’re Creole, but ethnically, racially, I’m a black man, I’m an African-American. We were never to sit in front of those screens regardless of our pigmentary ability to do so.

INTERVIEWER

“Culturally Creole” means what?

BAQUET

Well, you know, it’s different. I’m a New Orleans Creole. We’re descendents of free people of color and people of bondage. My family came here in the late 1600s from Haiti or Saint Domingue with marketable crafts skills. As young men, my dad and my uncles, most of them were craftsmen, and my heroes were craftspeople. The skill sets that I admired were of these tradesmen who were bricklayers and carpenters and plumbers and electricians who built their own houses, laid the foundations, and worked on their own cars. And to this day, the craft ethic is one of the most important aspects of our culture, you know, our work ethic, which we learned from our mothers as well as our fathers, this pursuit of perfection. And you’re right, this was something that I applied to my photography. I wanted a working nuts-and-bolts understanding of my craft, and I did it through thousands and thousands of exposures, just like that craftsman does it through thousands and thousands of handset tiles or handset bricks or precise cuts or nails driven into lumber. The pride that these men exhibited was tangible. There are great musicians in my family, my fathers’ brothers and his father, were architects of jazz: my grandfather, Theogene Baquet, was the founder of the Excelsior Brass Band, George Baquet, Archile Baquet were world-traveled musicians. I’m named for an uncle who was a great vaudevillian performer who was murdered in a Harlem nightclub by a fellow New Orleans musician. My father, Arsene Baquet, Sr., was an incredible vocalist and a master shoemaker. I learned to play the piano as a boy. We grew up downtown, in the Catholic Church. I attended Corpus Christi and Saint Augustine High School. I have outdoor skills and fishing skills that I learned down in Point A La Hache. Every weekend we eat like it’s Thanksgiving. And we claim all of our family, I have over 180 cousins. That’s what it means to be culturally Creole.

INTERVIEWER

The work or craft ethic you’re talking about is reflected in your “Labor” series, which is interesting, in part, because you don’t often see images of people working or of working-class people in New Orleans.

BAQUET

Look at these old houses here or at some of the old churches. If you go into the attic of St. Louis Cathedral or Our Lady of Good Counsel, you see those vaulted ceilings and you see the workmanship and how precise these huge timbers were cut and fitted. Oh, it’s admirable. The topside of that ceiling is like a boat, crafted inside out.

INTERVIEWER

So, is that workmanship and precision what appeals to you in your photographs of men and labor?

BAQUET

I did a four-year apprenticeship in the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. I’m a Union Electrician. That first job that allowed me to buy my cameras was as an apprentice electrician. I haven’t worked in the trade since, maybe, right after the World’s Fair in 1984, but the whole thing of Union craftsmanship, is that, electrical perfection was our product and the advantage we felt that we had over non-union tradesmen was our handing down this craft ethic, handing down the secrets of the trade. We spent months laying conduit pipe perfectly level and plumb only to have it covered up in concrete. What still appeals to me is their dignity, their pride.

INTERVIEWER

It seems that a lot of laborers in New Orleans today don’t share that ethic.

BAQUET

You’ll always find men who pride themselves in their craftsmanship. It’s easy to do shoddy work. But the craftsman has learned from his mistakes and…it’s something that you’re constantly aware of. You know that your next move, your next cut, your next stroke of the blade or the hammer or the saw or the shutter button, is going to be precise and predictable and predictability is gained through repetition. It’s not done by being perfect once. It’s done by getting it right and being perfect ten thousand times. They call us professional photographers but what the hell does that mean? You look at other people who claim this title of professionalism and you find your doctors, your architects, your lawyers, your engineers, and these are people who you expect to get the job right the first time, and yeah, that’s an awesome legacy and an awesome responsibility, but it’s something that you develop daily. It’s not a step, it’s a lifelong path.

INTERVIEWER

Shifting gears here, I know that you stayed in New Orleans after the storm. Do you have any reflections about that experience that you’d like to share?

BAQUET

Civilization is a very fragile thing, upheld by the threat of violence and incarceration. We hire young people with guns who allow us to sit in this fine institution and trust in our safety. We stayed for four days after Katrina and it was four days of horror. There were gang members and predators who had organized and were preying on vulnerable people. I saw the best and the worst in people and I’m lucky that I got myself and my family out safely. In the end, it was family that we resorted to, it was family that housed and fed and protected us. I mean, it changed me. I’m better for having experienced it, but I wouldn’t want to live through the horror of those first days again.

INTERVIEWER

How has that experience affected your photography?

BAQUET

I’m very fortunate to be able to do this for a living, but I don’t want to shoot anymore Katrina crap. I’m over it. I have images in my head that I didn’t stop to photograph that still haunt me, all those fires burning, hopeless people that I didn’t stop to help. I try to stay grounded in the present. I try to remember that my real subject, especially here at Loyola, is my people, my community. Photography is not just about the light, It’s the relationships, the space and the connections between people, or between the subjects in the photographs and the viewer of the photographs. That’s something that’s real. Sometimes the invisible is more real than anything, and photography can capture that.

{Further: Interview with Baquet in 1991 at Callaloo.}