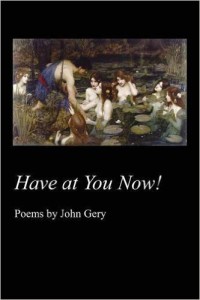

Have at You Now!, by John Gery. WordTech Communications, 2014. $18, 96 pages.

The poet John Gery is deeply concerned with the propensity of those in power to perpetrate mass violence. Expressed most directly in his 1996 book Nuclear Annihilation and Contemporary American Poetry: Ways of Nothingness, he explores how American poetry in the latter half of the twentieth century reflects and addresses this existential problem. In his sixth book of poetry, Have at You Now!, Gery turns his attention to the ongoing dilemma of the individual who possesses awareness of savage wrongdoing and the concomitant struggle of how to act in face of it. Gery has chosen Shakespeare’s tragedy Hamlet to provide the title, basic organization, and thematic unity in Have at You Now!

The book comprises five sections—“Bad Dreams,” “Quintessence of Dust,” “Bestial Oblivion,” “As a Woodcock to Mine Own Springe,” and “A Congregation of Vapors”—each named after a phrase from the play, and centers on the grief of living in a world whose governments act in self-serving, narrow, and deadly ways. Unlike Shakespeare’s protagonist, however, Gery mitigates that grief within personal relationships. Using an admirable range of poetic forms, he traces frustration at how little a citizen can (or is willing) to do to counter official ineptness and atrocity, and considers what in his life offers respite.

Gery hints at reprieve in the introductory poem “Clearance,” which is both about “an empty page” as well as “a loved one’s departure.” Using a line from John Donne’s “Valediction Forbidding Mourning,” “like gold to airy thinness beat,” Gery affirms with characteristic complexity both the potency and fragility of human love and desire. “Summit Summary,” a twenty-six-line poem consisting of one long sentence, depicts both the maddeningly tacit acceptance of those in charge of murdering innocents with a “mistargeted bomb,” and the powerless witness “overflowing with scholarly ambition but utterly forgotten behind his moldy stacks.” Like Hamlet, this poet is self-questioning, a stance which saves him from arrogance. Parsing the long sentence of this poem, the reader sees that the initial phrase “tactfully irrelevant” applies not only to the official’s “strategic plan” but also to the poet himself. Does the speaker in any truly efficacious way challenge the powers that be?

“Re: Volition,” a poem which contains the title of the book, concludes the first section and directly addresses the question of will. In Hamlet, Laertes utters the challenge “Have at you now!” Later Laertes dies by his own poisoned rapier. Here is Gery’s closing tercet:

Yet angrily to strike out would allow

too little time to think. Ah, that’s the trick

somehow to nurture without leaving stains.

What can a citizen do to adequately counter atrocity, and even if an answer presented itself, how firm is the will to action? Might the harm done in striking out in anger revert to the angry citizen, in this case the poet himself?

Whether or not the citizen-speaker of these poems acts against political wrongdoing, anguish remains. The love poem “Bestial Oblivion,” which gives the third section its title, reveals one remedy of a burdened mind: sexual desire. In rhymed quatrains that follow the metrical pattern of Hymnal meter (alternating iambic tetrameter and trimeter lines), the speaker expresses his longing for the beloved. This is just one of the poems in this collection in which Gery displays a facility for using formal prosody while keeping the language as natural as everyday speech. The poem ends, “I need you here. I need you fast / against me. Now. I’m mindless.”

The mindlessness in “Bestial Oblivion” does not last long, however. “Appeasement,” a six-page poem addressed to and using the long free verse lines of Walt Whitman, emphasizes the theme of the speaker’s failure to act in the face of widespread suffering, claiming that he had done nothing:

In the hiatus of days, months, years—between the wars

we lay out

like highways, wars we perpetuate by our building more

highways, wars we

export as though they were fuel for our highways,

thousands of highways on which to lay out yet more

corpses end to end—

This poem of self-disapprobation ends on a more forgiving note with an allusion to the child in “Song of Myself” who asks “What is the grass?” In the last section, the speaker calls on Whitman to remember when once the speaker reached out:

to a child collapsed in the grass by a hillside, so that

child might rise

reaching for me, not out of fear or disgust for all I have

done,

but to touch me, to embrace the spirit of things I once

said I stood for,

regardless of the trail of failure and lapse….

This gentler vision returns with the poem “Miracoli,” the last poem in the volume, in which the speaker and a companion visit a famous cathedral. The companion imagines hearing an “unearthly music that had arisen from the choir/ no choir present.” The speaker concludes:

It was silence I had sought, where she had found,

among the quiet parishioners, a fray of song.

I, who like to sing, pass on this memory, sprung

like a shout of sprigs in spring, from one now gone.

In these lines, Gery displays a wonderful use of sound to mimic the “unearthly music”—the resonant consonance of m and n and the sibilance of s.

Have at You Now! is a virtuoso performance, bringing together the poet’s wide prosodic range, his deep concern with the ability of humans to commit mass murder, and the question of how an individual manages to live and love alongside this destructive capacity. Add to this the ability to hit just the right tone, at once righteous and humble, and you have a book of poems that are demanding in their erudition but equally rewarding to the reader.

A native of New Orleans, Karen Maceira holds an MFA from Penn State. Her poems have appeared in numerous journals including The Beloit Poetry Journal, Louisiana Literature, The New Orleans Review, and The Christian Science Monitor. She has published reviews in The Harvard Review and essays in Hollins Critic and The Journal of College Writing. She currently teaches English in a suburb of New Orleans.