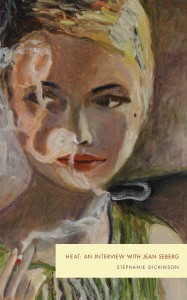

Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg, by Stephanie Dickinson. New Michigan Press, 2013. 63 pages, $9.

At the age of 17 in 1957, Jean Seberg was cast to play Joan of Arc in Otto Preminger’s film Saint Joan. A young girl from a small town in rural Iowa, Seberg defied the fate of most girls of her background and became an immediate success in both America and France. Over the next 20 years, she would appear in 34 films until, in 1979, she ended her life with a bottle of barbiturates in the backseat of her Renault.

Stephanie Dickinson’s portrayal of Jean Seberg in the fictional interview Heat is a truthful inhabitation of Seberg’s subdued, chaotic personality. Dickinson employs the form of an imagined interview, yet populates it with intricate poetic language, concocting a mélange of interview and prose poetry. Heat is an overlooked gem in both innovation of form and voice.

At first blush, the reader’s mind initially jumps to the renowned collection of fictional interviews Brief Interviews with Hideous Men by David Foster Wallace. But Dickinson’s subject, Jean Seberg, is not fictional like the hideous men that David Foster Wallace famously caricatured. One can look up videos online of real interviews with Seberg, which I did as soon as I sat down with the book and was not disappointed.

Seberg’s voice has a suspicious opaqueness throughout Heat. As a reader, I questioned the accuracy of the extensive prose that, at times, reads like a poem. Sentences on the first page of text, such as “When you swim in the forbidden sandpits the hydra growth invades and the town watches your white foot ease into hundreds of mouths” feel unsettled and jar the reader. But Dickinson slowly urges the reader into her occasionally dense style until they are fully submerged in the give and take between the interviewer and Seberg. Indeed, when one looks to the vintage videos of Jean Seberg speaking to interviewers, her voice shifts easily between extensive explanation and blunt brevity that stuns.

Seberg oscillates between playing with coy, falsified virginity and cursing her childlike looks, considered to be so attractive in the 1960s and 70s. Her answers often conflict and shift suddenly between terse one-word sentences and far-reaching prose. Dickinson takes advantage of this polarized style when Jean Seberg describes experiences on film sets—for her, often in foreign countries:

I can’t see my husband, only my breath. He falls, clutching the air. Sky. A copper sun beaten into the horizon. I scrape the scales from a fisherman’s knife and press them into my skin made sticky by the wind. You can drown in the little ocean inside. A stranger offers me a sea snake wrapped in a newspaper. A language of desert where water has crept. I hear the humming of the eel-like being. A gold fin runs the length of its blue ribbon body. A mane on its head rises into a magnificent crest as if a goddess had been punished for her murderousness. My performance was praised.

Alongside the rapidly altering style, the image of Seberg as an aquatic animal recurs throughout. With a sudden change of light, Seberg’s image shifts; her scales become dark, then flamboyantly iridescent. Seberg’s voice remains malleable and fluid alongside the interviewer’s frank questioning about her film career and numerous relationships with directors.

In contrast, when speaking of Seberg’s rural Midwestern childhood, which Dickinson herself shares, the tone becomes clear and decisive: “Morality in the Midwest keeps the skies grey; the snow, a black stone; the moon a torn piece of bread; and sex layers deep under the homespun dress.” Dickinson appeals to Seberg’s conflicted personality, torn between a child from deep, conservative farm country and a young woman whose childlike features the public cannot release from their grasp. The interview is further divided into Seberg’s varying identities:

Seberg: Midwestern Naiff

Seberg: Strangler of Sleeping Men

Seberg: An Accidental Actress

Seberg: Diego’s Mother

Seberg: Black Panther

Seberg: On Location

Seberg: Expat

Seberg: Late Night Habitué

Seberg: Comeback

Even the table of contents is rife with contradiction, inherent in Seberg’s broadcasted image, yet it repeats her name. While the public gaze idolizes and criminalizes her, Seberg’s name continues to ring, and the public cannot tear her image away—only further blur its edges.

Reading Heat, the reader is consistently reminded of Seberg’s name as attached to her many identities. These identities result from a personality plagued by sexism in the eye of media and the pressure to stay the perfect, young American girl. The interviewer asks, after the FBI planted a story that Seberg’s second child would be that of a famed Black Panther instead of her husband, “Subsequently, you took an overdose of barbiturates? Why?” Seberg responds, “You know why, don’t you? They called me the last all-American girl and so I could never forsake the Midwest.”

Jean Seberg’s voice resonates in stark contrast to that of the interviewer in Heat. The interviewer appears sympathetic toward the effects of fame on Seberg’s mental illness, but does not excuse her for her absence from her first son’s life:

Q. Help us understand why Diego ultimately had two mothers—his surrogate mother and you. Outwardly, two women could not have looked more unalike—Eugenia, overweight, suffering from phlebitis in her legs; and you, a beautiful film star. Is it true that when you tried to pry him away from her he would throw savage tantrums?

The interviewer’s voice cuts into Seberg. He or she is anonymous, yet all of the questions are in italics, as if they merge with Seberg’s inner monologue. The interviewer clinically questions Seberg on not one but many suicide attempts—the first involving the stillborn birth of her second child. Seberg laments:

Night swims.

The waning town drowses.

I’ve drunk myself sober on darkness.

Each year on the anniversary of my baby’s stillbirth I attempt suicide. Have I any flesh left? Seven months pregnant I swallowed barbiturates thinking we’d both die, but then I survived.

Jean Seberg’s voice is unapologetic, sensual, and deeply harrowing. It is one of post-suicide, but far from morose. From beyond the grave, Seberg reflects on her motherhood, civil rights activism, French-American identity, and ultimately, the effect of the public’s constant eye on her psyche—all in a book thinner than a slice of bread. In Heat, Stephanie Dickinson provides the platform, and Jean Seberg’s complex, emotive voice takes center stage to deliver a lasting performance.

Sarah Neal is a senior at Loyola University New Orleans. After graduation in 2019, she will attend a master’s program for opera performance and continue writing in her spare time.