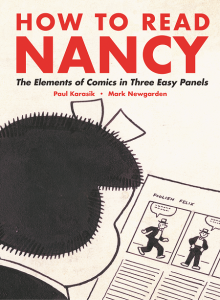

How to Read Nancy: The Elements of Comics in Three Easy Panels, by Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden. Fantagraphics, 2017. $30, 276 pages.

To read Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy is to slip momentarily in time, back to a lazy mid-century morning of simplicity, stretched out upon the living room floor with the funny pages. Amidst the hijinks of Blondie, Beetle Bailey, and the pulp of Dick Tracy and other serialized adventurers like Tarzan and Buz Sawyer, readers could rely on one peppy little girl to tromp her way through daily gags with everlasting, ageless aplomb. The dotty-eyed Nancy, with her iconic hair like a toothy cogwheel, and her best pal Sluggo regularly found themselves in a pure sort of trouble, adorably innocent follies of a bygone era. From her 1933 debut in Bushmiller’s Fritzi Ritz strip to her solo syndication throughout the majority of the following century, Nancy went on to inspire artists like Andy Warhol and Joe Brainard, as well as celebrated contemporary cartoonists like Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware, all of whom were moved by the strip’s careful balance of minimal simplicity and maximum charm. “The mortar that held these daily gag bricks tight through the decades was basic, iconic, coin-of-the-realm truisms,” Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden explain in their terrifically erudite investigation How to Read Nancy. “An ice-cream cone is a kid’s best friend, school is a drag, bums are lazy, blondes are cute, bullies are dumb….”

In one strip from the summer of 1972, Nancy drops into the local bank’s loan department to ask for two dollars. “What for?” replies the bald, hilariously mustachioed man behind the desk. He appears to be in the middle of some paperwork, and has not one but two phones in front of him, as if to double the tense anticipation of an important call erupting through the office. “The circus is in town,” Nancy tells him. “Is it?” he replies, incredulously. Nancy and the banker don’t finish their conversation, or at least in any way that we can see: in the strip’s fourth and final frame, they are seated side-by-side in the front row of the circus, enjoying an ice cream cone together while watching the clowns.

It’s perfect. And it’s not only a sweet gag—the more one pores over this simple cartoon the more brilliance shines through. The pacing, the direction, the fine rendering of Nancy’s sensitive but hopeful face as she looks up to tell the banker about the circus, the fact that Bushmiller pulls the “camera” around behind the man’s desk, so we, too, can momentarily look down at—and straight into—the face of a kid with a dream. But most perfect is the banker, in the final frame, positioned almost exactly like he was earlier, sitting behind his desk. Instead of a fountain pen he’s got a freshly scooped cone, not a drip in sight, and his eyes are closed, lids blissed-out in that lacuna-shaped arch of cartoon happiness. He wants to hold on to this moment, to that youthful innocence, for as long as he can.

Bushmiller knew that humor could transcend aging, that a consistent, frozen-in-time silliness would alleviate the complications of not only a maturing audience but an evolving world. “Older readers love to laugh at Nancy because she’s still the same pert, merry kid they laughed at when they were younger,” Bushmiller wrote in 1966. “If she were older, they’d realize they’re older too…and the laughter would have a touch of sadness in it.” With Nancy, he allowed readers a way back, the means to return to simpler time, before everything got complicated.

Curiously enough, Bushmiller worked backwards on his way to “discover and delineate ‘the perfect gag.’” He’d always start with his punchline and work his way through the setup in reverse. “The last panel—or as he put it, ‘the snapper’—was the visual conceit that substantiated the sum of the whole and became of utmost importance to his work.” “He routinely claimed the Sears, Roebuck catalog as a major inspiration,” finding a familiar mirth in the various new items that were consistently appearing in American homes. Popular toys and appliances, from squirt guns to radios and refrigerators were endless sources of relatable humor. “I want the stupidest guy in the world to get the gag!” he once remarked. That sounds easy enough, particularly so considering the childish, everyman slant to much of Nancy’s humor. But there’s so much more to these strip than “the snapper”: while the stupidest guys in the world will find something in every Nancy cartoon to smirk at, other readers might marvel at what makes these cartoons work the way they do. How can a simple strip about something like a squirt gun fight instantly transport readers generations back to revel in a time in which they may not have actually even lived? How are these strips so effective?

Comics scholars Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden know exactly how, and explain Bushmiller’s genius in their dizzying illustrated essay How to Read Nancy. Full of appendices that would delight David Foster Wallace, How to Read Nancy is a slow-motion dive through the substructure of the comic strip. Using a single gag as a centerpiece, Karasik and Newgarden peel away the foundational elements of the strip and showcase, from its shadows to its word bubbles to its motion lines, how splendid Bushmiller’s comics truly are.

August 8, 1959. Three panels. Sluggo sports a western holster, likely straight from Sears, Roebuck, with a star prominently on display like he’s the new sheriff in town. “Draw, you varmint,” he declares in the first panel, cruelly squirting a local girl smack in the face with his water pistol. Nancy watches from the foreground. Sluggo’s relentless; in panel two he’s changed direction, this time shooting a boy while snarling out another “Draw, you varmint.” In the third frame, Bushmiller’s snapper, he lurches maniacally towards Nancy, reaching for his gun, but she’s ready for him: she’s got a holster of her own, secretly concealing the snakey, dripping garden hose that’s connected to the nearby house. “Draw, you varmint,” he says again, likely his last words before Nancy blasts him in the mug.

Although not as sweetly nostalgic as Nancy at the loan office, this strip is a prime example of Bushmiller’s airtight visual economy. “It’s so thoroughly thought through,” James Elkins writes in his introduction, speaking of Bushmiller’s meticulousness, “so precise in its unnatural conventions, so stringent with what it permits on the page, that it’s less a cartoon than a diagram.” “Comics are primarily neither drawing nor writing,” Newgarden and Kararsik explain, “but they are, in some respects, like simple machines, designed to communicate swiftly and efficiently and with all working parts laid bare.” But Nancy has a “deceptive simplicity,” possessing a hidden cache of “formal rules laid out by a master of design.” Following an exhaustive biographical introduction chronicling Bushmiller’s “copy-boy-to-art-room track,” Karasik and Newgarden chart out Bushmiller’s theoretical blueprints and painstakingly revisit the individual elements of the “draw, your varmint” strip over the course of forty-four illustrated chapters.

Each chapter of How to Read Nancy reprints the strip, but isolates the element in discussion: Chapter 26, on “Gesture,” replaces the strip’s players with all-black silhouettes and marvels at Sluggo’s bullying stance and his victims’ over-the-top recoil. Chapter 28, “Lines of Vision,” zeroes in on the peculiar fact that Nancy’s face is never shown in the strip (she watches the action with her back to the viewer in panels one and three): “her lack of eyes (and affect) invites us, in a way, to join our own along with hers.” In Chapter 18, “The Background,” Karasik and Newgarden erase all the characters and weaponry and celebrate Bushmiller’s familiar settings, and how the house’s lap siding, slat fence, and perfectly central leaky spigot conjure a familiar mid-century American charm. Bushmiller’s a geomancer with “an idealized, iconic sense of place, as dreamlike as [Krazy Kat’s] Coconino County in its day-to-day liquidity.” Chapter 30, “Spotting Blacks,” is particularly illuminating, and details Bushmiller’s calculated usage of black ink, namely in Nancy’s hair. “Bushmiller understood that a reader’s eyes will always follow the solid black and provided accordingly. Nancy, in order to be a successful starring character needed to be of primary visual importance….”

But what How to Read Nancy does best is slow things down. Nancy has the strength to unmoor its readers in time and set them adrift, and Karasik and Newgarden have the intelligence and passion to hold that wormhole open. By repeatedly circling back to the nuances of a single strip, the authors appear to make August 8, 1959 last forever. And that timelessness—that reveling in a memory of a single day—is the best tribute one could give Ernie Bushmiller. Nancy comics have the potential to pass too quickly (the cartoonist Wally Wood once remarked that it’s “harder to not read Nancy than to read it”), but Karasik and Newgarden show precisely how these strips should be enjoyed: left-to-right, slowly, and back, towards time immemorial.

Jeff Alford is a Denver-based critic and book collector. He works as a gallery archivist and writes for Kirkus Reviews, Run Spot Run, and Rain Taxi Review of Books.