DIY in New Orleans

The first art opening I attended last spring after the long lockdown was at Wading Room Gallery on Alvar Street, a new and temporary space created by Peter Hoffman and Ryn Wilson. Though I usually avoid openings, I wanted to support the new project, was curious to see what was there, and maybe just needed to get out of the house. The gallery, a garage with its doors open to a short driveway and lawn, got me thinking about the spaces–current, past and future–to see art in New Orleans.

New York had formed my ideas about art venues, what they were and how they operated. In 2008, I moved to New Orleans. This was just before Prospect 1, the city’s first biennial of that name curated by Dan Cameron. It was a city-wide exhibition like the Venice Biennale, which I had never been to. This way of looking at art in bedded in a city what is new to me and appealing. The following spring I went to an event at KK Projects in the St. Roch neighborhood. The interior space could have been a gallery in Chelsea. But outside was a dark street with several blighted houses, women in sparkly cocktail dresses and high heels stepping through a path of rotting boards and broken glass between buildings. “What is this place?” I thought. And New Orleans seemed made for DIY.

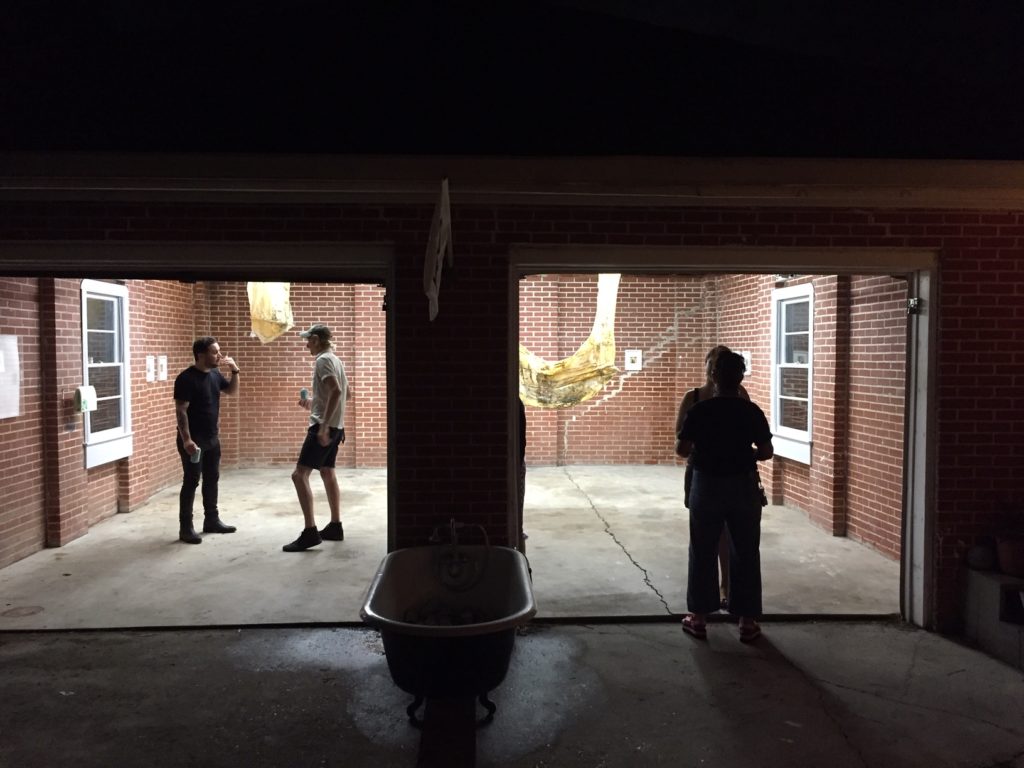

New Orleans has changed a lot since I moved here, but showing up at Wading Room reminded me that this city provides an ideal environment for toying with what defines an art space, what the goals are, and who is on the guest list. Wading Room Gallery was a garage with a brick interior. With the door open, the opening was pandemic-friendly. The idea began as a daydream in lockdown life. I met Peter Hoffman and Ryn Wilson at the opening and we communicated after by email for this piece. Peter wrote:

“During the unemployed, black-hole early pandemic I had been using half the garage as a wood shop, wondering if I should try to start selling birdhouses for a living…I have a page in a sketchbook labeled ‘List of disappearing ideas’- things that would be great to do but [I had] no motivation at the time.”

Wading Room was one of these ideas.

The inaugural exhibition was a two-person show: soft sculptures by Jacob Reptile and paint-by-number paintings by Robin Ruina. Peter told me by email that he had mentioned his idea for the gallery to his manager who asked, half-jokingly, if he was interested in showing his wife Robin’s paint-by-numbers paintings. Peter said, “I loved the idea of showing work that would normally be regulated to that of hobby-related activity as serious stuff. It is serious stuff…”

The paintings were just what they claimed to be: paint-by-number paintings from kits bought online, something to stress-cope and pass the time during the pandemic. This made the fact that they were appealing to seasoned art viewers strange and amusing. They were skillfully made, curated and curated. They sparked interesting conversations about what makes a painting a painting. Some viewers didn’t realize at first they were paint-by-number paintings, but one could see in some places, especially on the edges, tiny numbers, indicating which color should be applied.

Peter and Ryn had decided to call the space Wading Room Gallery, playing with the former use of the adjacent home, a doctor’s office, and the fact that, like everywhere here, the floor tends to flood when faced with copious amounts of rain.

That night I spoke with Robin, an English literature professor. “How do you feel about seeing your paintings in this context, in an art gallery?” I asked after we had been talking for a few minutes. “Uncomfortable,” she said. Her answer was so honest and interesting. This conversation about context and curation continued that night and after. An art space offers a place to go and things to talk about. After a year of virtually everything being virtual, real people, real place, real art was beyond appealing–it was elemental.

Wading Room is a terminal project. There are many advantages to including an end-date to a project like this, especially when the creators are artists themselves. The foray into space-making and curation teaches an artist so much, and when it concludes, the artist can return to their more introverted purpose, to make art. There will be a total of six exhibitions at Wading Room, each documented in a well-designed zine with photos and an essay.

Sometimes I wonder why I live here (I know, I know), especially when I return as I just did from spending time in New York. Here is why, art-wise, it makes sense to live and work here: New Orleans is a place to daydream and that is the special calling of artists, than being part of a scene or market. Space and time are more readily available here than in many high-drive places. Peter Hoffman’s “disappearing idea” of creating a pandemic-friendly gallery in his garage proves that with work and a level of seriousness—seriousness can be the hard part here—it is possible to build something seriously great. When I asked Ryn who they wanted to come to Wading Room, she answered, “Anyone interested in art.” Who isn’t? I mean, if you see art in the afternoon, chances are you will be more interesting in the evening.

Showing up for the inaugural show at Wading Room had something to do with my motivation to check out Under Nine, another new gallery space I learned about on Instagram, not through the local art accounts, but skateboarding ones. On a Saturday night in late June, I drove out to Chalmette. I passed by the address several times before I figured out where to go. I felt like I might be going to a rave and not an opening, but hey, this is a speak-easy town. When I showed up right at the start time (nerd), I felt as though I had time-traveled into a basement of bros in Upstate New York in the early ‘90s. Because I was so early, the art opening had not really started, though all of the art was installed (not always the case with the Saint Claude galleries). It was basically a bunch of guys skating and hanging out in the back so I had the gallery to myself. The spacious white-walled gallery was separated by lighting and a half wall/DIY bar from a back corner seating area and space where bands set up. In the far back was a wooden skate bowl.

I asked who was in charge of the art show and spoke with Chance. He envisions a multi-use space for art, films, music, and, of course, skateboarding. This first show “Skater Art” was mostly his friends, other skaters. Dom Crescioni’s cheery little FUCK OFF! sign had all the skill, charm, and innovation you could want in a text-piece made of wood, oil-based paint, glass, gold leaf, and weed. Both Dom and Chance described the show’s primary motivation as simply to share art with friends. Chance said he was thinking of monthly shows but had not planned too far into the future. I saw later on Instagram that the art show was well-attended, even before the band went on. Bravo emoji.

Some home-grown art spaces that have been around a while. Sheila Santamaria initially created Alone Time gallery, a storefront attached to her home in the Treme, to show her own work, then went on to show other artists, always a solo show, at irregular intervals. The focus of these shows (other than handing the space over to an artist) is the opening event, which usually includes a performance, band or DJ. Sheila said he wants to create “an environment to have fun in…a place where everyone feels welcome.”

Prospect 5 (now a triennial) opens in October. This four month exhibition again promises to take art viewers off the beaten path. (If you see art in November, you will be more interesting in December.) It’s a great way to see the city. It’s also worth thinking about and re-thinking: what should an art venue do and for whom? Meanwhile, artists and friends of artists, if you have an idea, a space, a wall, build it, we will come.