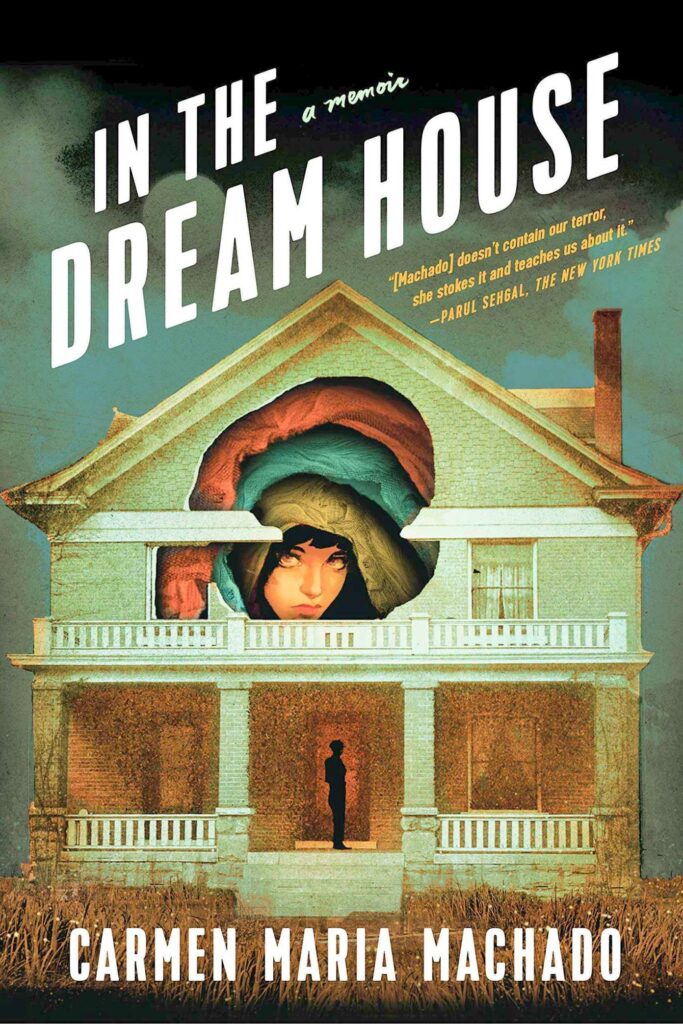

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado. Graywolf Press, 2019. 264 pages.

Those familiar with Carmen Maria Machado’s work have become comfortable with the distasteful, with the unfamiliar, and with the pseudo-absurd. Her first short story collection, Her Body and Other Parties (The National Book Award finalist and winner of the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Prize) is often categorized as simultaneous “domestic fiction” and “science fiction,” or “magical realism” as it often pokes and prods at the truly small differences between the genres, investigating them at every turn. The collection taunts readers with their own expectations for what a short story collection should be; one story tells of a post-apocalyptic wanderer’s cross-country sexual exploits, rather than detailing the multitudinous horrors of the disease or their environment–the character’s various partners show their genuine need for intimate connection in a desperate time, but their real plight is searching for anyone else alive.

A similar predicament is present in Machado’s first memoir, the widely acclaimed In the Dream House. The book is told through vignettes of varying length, often jumping forward and backward in time to piece together a tale of trauma, abuse, and most importantly, survival. In the Dream House subverts the reader’s expectations on every level–readers expecting a traditional autobiography or memoir will be surprised as this book, rather than portraying a section of the author’s life as a neat chronological series of events, embraces the way trauma imbues a survivor’s thoughts and actions often without one even knowing, long after the inciting incident–this book warps in on itself, fumbles with some details while remaining steadfast and certain on others, and allows time itself to feel fluid and unforgiving. Still, this book, despite some of its marketing, does not fall neatly into the category of magical realism, either–it seems much closer to the real than Machado’s previous work, as perhaps anticipated by the genre.

Trauma and abuse warp a survivor’s sense of time, place, and the self. In the Dream House allows itself to feel at times warped and confused, always holding its reader close as we are seduced by sauntering sweet gestures before we, too, are cowering in a windowless room. The overarching motif in this memoir is the nature of a dream house- -a home, standing big and tall, masterful architecture encasing curated decoration, a marker of stability, wealth, and dedication. The mythos of the dream house holds a narrative of completion, as if the dream house is the final prize for winning a marathon or two, but Machado’s dream house isn’t metaphorical–it is rife with painful memories, and it is very real. Acknowledging metaphor, though, Machado interlaces each vignette with a different narrative or personal trope, often citing Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk Literature i n her analysis of this part of her life. The dream house takes on these heavy histories of long-familiar motifs and tropes in the titles of each vignette: “Dream House as Bildungsroman,” “Dream House as Pulp Novel,” “Dream House as Choose-Your-Own-Adventure.” But the genre-bending doesn’t end there–the dream house is also, simultaneously, Hypochondria, Deja Vu, and Epiphany. These tropes inform the vignettes contextually, representative of the clawing desire to categorize an abusive experience into something out of which some sense can be made.

The memoir has an academic edge, too. It takes its reader through the oft misunderstood and underrepresented world of a psychologically tortrous, abusive lesbian relationship. Machado takes the opportunity to not only relay her abuse through tightly wrought sentences and exhilarating, intoxicating, possessing paragraphs, but through the same gorgeous language she criticizes the society within which she experienced this abuse. There is a prevailing, false narrative that lesbian relationships must be idyllic, utopic from their foundation up; on top of that, popular society finds it difficult to accept that women are ever the instigators in abusive situations–woman-as-abuser seems far away and ficticious in world where women are frail, fragile, and must be protected. But what happens when the woman must be protected from another woman? Machado investigates this question not only with ample exhibition of her own abuse, but with rigorous accounts of historic lesbian and queer abuse–including, though not limited to, the extreme difficulty queer survivors face following escape, if escape is ever possible. “Dream House as Ambiguity” takes its reader through various historical accounts of woman-as-abuser, and takes on the troubling histories of lesbian-as-battered-woman, referencing Annette Green’s and Debra Reid’s cases. In this vignette, Machado also spotlights the insidious racism present and often shadowed in queer communities–these interwoven and intersectional oppressions all collide to make documenting any history of domestic abuse arduous. These names are often forgotten in femininst and even lesbian circles, and Machado acknowledges that readers cannot argue for the protection and understanding of lesbian survivors without first, at the very least, acknowleding the history of lesbian abuse.

This book is full of challenges. It asks its readers to reconsider the nature of genre and our expectations when entering a text of any sort, in this case, a memoir. It asks us to recount our own dream houses, where they come from, what we’ll actually see if we ever get there, and if they have an escape route built in. As a reader, there were moments this book sent me into full hysterics–moments it got too real, moments it got too scary, too reminiscent of my own experiences. There were also moments of great hope in this book, moments where the language is so brilliant in its craft I had to read sections out loud just to hear them come alive. Machado’s ability to conjure such strong, specific emotions in her readers is a testament to her prowess as an author, and the power in her story. Machado’s memoir takes its reader through the depths of trauma, abuse, fear, and reconciliation. It is a story of moving on, of breathing easier, and, most importantly, of survival.

Kimberly Pollard is a third-year student of Creative Writing and Women’s Studies at Loyola University New Orleans; through her time in college, she has renewed her love of writers who break and bend the rules of genre and language. She is particularly interested in writers who tackle trauma, and especially domestic violence survivorship, both through prose and poetry. She is honored to respond to a soon-to-be-seminal text like In The Dream House.