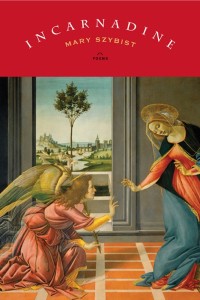

Incarnadine, by Mary Szybist. Graywolf Press, 2013. $15.00, 80 pages.

“I’m not religious, I’m spiritual”—at long last, the eye-roll inducing mantra is granted explanation and elegance in Mary Szybist’s second collection of poetry. “Incarnadine” is a word whose Latin roots (from “incarnare”) mean literally “to make flesh,” but its modern meaning of “blood-red” or “to make red” was first used by Shakespeare in Macbeth. Szybist explores both in this collection; the epigraph to the book is a quote from Thomas Hardy, “Repose had again incarnadined her cheeks.” She extracts classic religious imagery and, weaving it throughout several experiments of form and style (some poems reminiscent of e e cummings with scattered bits of punctuation and half words, others many pages of paragraphs, some rhyming, others not), uses it as the backdrop for modern scenes of nature and raw human experience. In “Invitation,” for example, she addresses all manner of Earthly angels: “If I can believe in air, I can believe / in the angels of air… angels of embryos, earthquakes…Angels of prostitution and rain…Angels of water insects.”

The Annunciation, the Biblical announcement that the son of God is going to be made flesh (and presumably the inspiration for the title), is her focus throughout the collection; she shows us how it occurs every day between flowers, birds, politicians, girls in dresses, and famous writers. It becomes less of an angel speaking to a girl and more of the revelation it entails, small moments in which godliness and elevation leak through. In “Annunciation in Byrd and Bush,” an ominous stranger speaks to a girl using only direct quotes from the speeches of those men: “I don’t need to explain, he says, / (his sleeves swelling in a nudge of air) / —but the highest call of history, / it changes your heart.” That “angel” with his swollen sleeves appears in many forms in other Annunciations: in “Annunciation as Right Whale with Kelp Gulls,” he is a flock of birds, feasting on Mary’s living whale body: “For they / swoop down on her wherever she surfaces. For they / eat her alive. For they take mercy on others and show them the way.” In “Girls Overheard While Assembling a Puzzle,” the Annunciation appears for a split second in childish musing: “And are we supposed to believe / she can suddenly / talk angel? / Who thought this stuff / up? I wish I had a / velvet bikini.”

Szybist shows us that the Bible is (metaphorically) like life in a decidedly non-religious way, not shy to address the horrors (and even boredoms) of heaven on Earth. “Another True Story” tells of a variety of mundane saints: “Saint Good Luck. Saint Young Man who lived through the war. Saint Enough of darkness. Saint / Ground for the bird. Saint Say there is a promise here…. Saint Shoulder, Saint Apostrophe, Saint Momentary days.” Nature is the apex of the experience: in “Annunciation as Fender’s Blue Butterfly with Kincaid’s Lupine,” for example: “I’d fasten myself / to the touch of the flower. / So what if the milky rims of my wings / no longer stupefied / the sky? If I could / bind myself to this moment, to the slow / snare of its scent….” In “How (Not) To Speak of God,” Szybist invokes His name in several lilting, emotional phrases arranged in lines splayed out in a never-ending spoke—perhaps a play on the Alpha, the Omega, the beginning, and the end, but also reminiscent in its shape of the sun or a faraway glowing star (and in its lines: “whose face is electrified by its own light”).

Szybist’s collection evokes the old Catholic direction to find God in all things, but you don’t have to be Catholic to understand exactly what she’s getting at. Rather, she merely exposes the supernatural as it occurs among us every day and invites us to marvel at the spiritual heaviness of the world—which, even in its darkest moments, she skillfully demonstrates as beautiful.