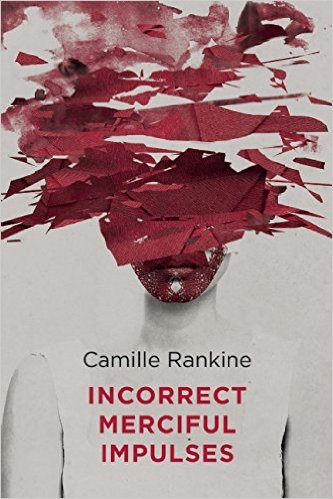

Incorrect Merciful Impulses, by Camille Rankine. Copper Canyon Press, 2016. $16, 80 pages.

In the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, the neo-conceptual artist, Jenny Holzer, created several series of posters and broadsheets, consisting entirely of truisms intermixed with quotes from figures such as Emma Goldman, Vladimir Lenin, and Máo Zédōng. Holzer distributed these works throughout New York City; Holzer’s guerilla art seeks to interrogate how political discourse and the rhetoric of advertising informs violence, sexuality, and power dynamics in public spaces. Camille Rankine’s debut collection, Incorrect Merciful Impulses, borrows its title from Jenny Holzer’s text-based art pieces. Like Holzer’s Inflammatory Essays, Rankine’s poetry seeks to propel the passive reader into active and aggressive questioning. With intense lyricism, Incorrect Merciful Impulses charts the anxieties, the blindness, and the perplexities characteristic of urban life in contemporary America. Rankine’s poetry thrusts its readers into a dialogue with the many quandaries of 21st century living, examining the costs of mass consumerism and the digital revolution. Compassion foregrounds Rankine’s poetic inquiry into the confluence of identity, history, politics, mortality, and culture, in a nation endlessly implicated in violence, domestically and overseas. For Camille Rankine, only the authenticities of art might provide the antidote for those of us marooned in our bodies, overwhelmed by the market, circumscribed by the pixel and the URL.

“Tender,” the first poem of the collection, contains a series of conflicting salutations, which clearly delineate the existential problems that Rankine obsessively returns to throughout Incorrect Merciful Impulses. The poem begins:

Dear patriot

Dear catastrophe

None of this means what we thought it did

Dear bone fragments

Dear displacement

Dear broken skin

I am in over my head

Here, Rankine apostrophizes doubt while introducing the notion of a correspondence between text and reader that is grounded in social intimacy and threatened by the brutality that surrounds cosmopolitan life in the United States. This is a poem that speaks to “the prisoner,” to “the wounded,” to “the bad animal,” to “the caged thing,” and to those whom William Carlos Williams called “the pure products of America.” In the poem, “Little Children, My Apologies,” Rankine further explains the problem:

In my comfortable way, I come to learn, the dangers

are many and oblique:

the microwave will kill me, this plastic bottle, this air,

this meat, my debit card and its hidden fees. I’m telling you,

I have no power here. I’m just a dummy swaddled

in worry and want, tethered

by two small rooms, a few small thoughts.

Tethered by two small rooms, crushed by one thousand oblique dangers, stifled inside an air-conditioned nightmare, Rankine’s poetry yearns for and bestows a spiritual largesse. However, despite this yearning and this bestowal, “we arrange our dreams against the wind,” and our words fail us; in “Symptoms of Prophecy,” Rankine notes: “In the new century, / we lose the art of many things,” and “the struggle/ is authenticity.”

Incorrect Merciful Impulses does far more than merely articulate the struggle to speak authentically in the digital era. Rankine makes palpable the concerns facing ordinary Americans in the opening decades of the new millennium. In “The Free World,” Rankine says:

I bind my old grievances

to a helium balloon. A long memory,

I have been warned,

is a cure. Everywhere I go, someone

has something they must say about you.

Nobody knows who we are. Wouldn’t you say,

nobody agonizes like we do.

Elsewhere

is a promise and a threat.

I have been proscribed

compassion of the wrong sort, and so

I am alone. I am

invisible within you. Seeking companionship

I spend my afternoons before the windows

of pet shops and strangers, trying

to decide. After all, I was told

I could have everything.

“The Free World” dramatizes the dangers of solipsism brought on by consumerism. Living in the free world, a world of “proscribed compassion,” where the twin dictates of self-help and self-esteem propagate myths of universal access and equal privilege, creates, for the speaker in this poem, a deep underlying loneliness. For Camille Rankine, poetry is the helium balloon to which one might tie one’s old grievances. Even as these grievances ascend, we remain “all crave, take, thirst,” but reading Incorrect Merciful Impulses we are comforted because we are not alone in our flawed and constant striving.

Dante Di Stefano’s collection of poetry, Love Is a Stone Endlessly In Flight, is forthcoming from Brighthorse Books. His essays and poems have appeared in The Writer’s Chronicle, Shenandoah, Brilliant Corners, Iron Horse Literary Review, and elsewhere. He lives in Endwell, NY.