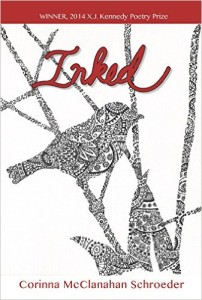

Inked, by Corinna McClanahan Schroeder. Texas Review Press, 2015. $9, 55 pages.

The bildungsroman, or coming-of-age story, is a literary category that contains some of the most well-loved books in all of literature: To Kill A Mockingbird, Jane Eyre, The Catcher in the Rye. But the roman part of bildungsroman tends to exclude poetry from this genre; after all roman is both German and French for “novel.” Corinna McClanahan Schroeder’s debut collection Inked, winner of the 2014 X.J. Kennedy Prize, crosses this genre barrier, giving readers coming-of-age poetry that charts a young woman’s adolescence and twenties and reminding us of the powerful role that narrative can play in poems.

The collection begins with the title poem, about the speaker getting a tattoo. We aren’t told what the tattoo’s image is, exactly, only that the pain of receiving it is part of the point: “I wanted to say, / … ‘I’m here for hurt.’” At home, the speaker takes off her bandage and witnesses “what the body can do, what the body can say.” The poem is a dynamic opening to the book’s first section, in which pain (at times self-inflicted) courses through the speaker’s life like the unnamed rivers in the landscape of her childhood. It speaks, as good opening poems should, to the book’s whole: the way Schroeder is marked by her young life, her family history, the Midwestern landscape where she spent her childhood, and the indelible imprint of her husband and his history.

I’m using the singular “speaker” here deliberately to describe the voice of the book as a whole, something I wouldn’t normally do, neither in a review nor in my head. Although a few of the poems are in the third person, with titles like “The Stage Carpenter’s Wife” that, out of context, might flag them as persona poems, in the larger scope of the book, it’s clear that Schroeder’s project isn’t to construct a multi-vocal text. The repetition of seemingly personal details across poems, for example, and the narrative impulse in the book both point toward the detailed construction of singular consistent voice, much like a novel’s narrator.

Inked reaches peak dynamism in the opening section, when the speaker is youngest and most imperiled. Everywhere she looks, her culture reflects back images of damsels in distress; “Reading Edith Hamilton in Ninth Grade” introduces the speaker to the sexually violent world of Greek mythology: “Girls’ legs splayed by boars / and bulls and swans.” One of the strongest poems in the book, “Maududo Lessons” expertly captures the danger and blind vulnerability of being a teenage girl. In it, the speaker believes in her own strength and ability to take care of herself because she excels at martial arts. In retrospect, she admits, “I didn’t know how sixteen / I looked or was.” Though she’s capable, in the confines of her classroom, to keep up with men through roundhouse kicks and chokeholds, she is heartbreakingly unable to access her own power where it would affect her most. Of her maududo instructor, the speaker says:

One night I asked how

to escape a straddling. Didn’t mention the wet grass or how I’d wished

I were home safe in my sheets.

Though this first section features the speaker consistently in high school or college, like many poetry collections that contain a narrative arc, Schroeder avoids close chronological order: poems from the speaker’s young childhood, for example, appear in the final section, emphasizing the book’s thematic logic above linearity.

Like many bildungsroman, Schroeder’s poetry employs anecdote to reveal an emotional or psychological truth about the speaker. In “The New Poetry Instructor,” near the end of the volume, the speaker (this time in the third person) recounts asking her students to write “about a first-time experience, / unaware so many’d pick the same.” At first, she is disappointed that her students overwhelmingly choose to write about their first times riding a bike. She points out “the dangers of the sentimental and cliché.” But then she recalls the vividness of her own experience:

her father’s hand

gripping the seat, her body bumping along

in after-dinner heat.

Like her students, her memory ends with her falling and sustaining a minor injury, and the poem ends bittersweetly: “How she’d like it back—her father / already running, help just behind.” This last line performs three functions. In addition to being a statement of nostalgia, it reveals the speaker’s vulnerability as a new, young teacher, as well as links back to the book’s opening image of a young girl surrounded by danger.

The last way that Inked seems to inhabit a novelistic space is through its largely straightforward use of language. Since narrative and epiphany are driving forces, there is less emphasis on knotty explorations of language. This is not to say that Schroeder’s work is unmusical. Like Frost, whose work bears some kinship to Schroeder’s, the poet makes masterful use of highly rhythmic lines that often approach blank verse, as well as the occasional surprise of internal rhyme. Schroeder’s restraint calls attention to the more sensual turns of phrase—much as a novelist might. Moments like the one in the poem “Gathering,” then, where two lovers are described (“How in foreplay, before the foregone / fingers climb the knobs of a naked spine”) remind me of Howard Nemerov’s poem “Because You Asked About the Line Between Prose and Poetry.” There, Nemerov describes what we would call a “wintry mix.” Suddenly, the rain resolves itself into flakes: “There came a moment that you couldn’t tell / And then they clearly flew instead of fell.” Schroeder’s book is much like this: exploring the space where language—and the speaker herself—begin to take flight.

Colleen Abel is the author of the chapbook Housewifery (Dancing Girl Press, 2013). A former Diane Middlebrook Poetry Fellow at UW-Madison’s Institute for Creative Writing, she has published work in Colorado Review, The Southern Review, Pleiades, West Branch, Cincinnati Review, and elsewhere.