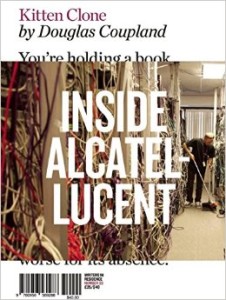

Kitten Clone, by Douglas Coupland, Visual Editions, 2014, $40, 150 pages.

The London based book publisher Visual Editions‘ “Writers in Residence” series pairs narrative nonfiction with Magnum photographers to create a body of work that exemplifies the power of well-controlled photojournalism. Douglas Coupland’s Kitten Clone, the third book in this series, chronicles the author’s discovery of the quiet but integral corporate world of Alcatel-Lucent. The French telecommunications giant has a worldwide presence, functioning at the top of a pyramid of technical, data-connective necessities. “Were it to vanish tomorrow,” Coupland writes in his introduction, “our modern world would immediately be the worse for its absence, with global communications severely crippled until its competitors swooped in to fill the void.”

Journalism is at the core of Kitten Clone. Coupland reveals a surprisingly down-to-earth corporate world. In book’s first section, “PAST”, Coupland meets with Markus Hofmann, the head of Bell Labs Research in New Jersey, a place lost-in-time “that seems like it was once very elegant but then had some kind of stroke and just sort of … stopped.” They discuss the history of Bell Labs and how it prepares for the future. “Until there’s a fundamental new way of doing things,” Hofmann explains to Coupland in an empty office: “we’re going to have to test the limits of bandwidth… Nobody expected your thirteen-year-old daughter to want to watch high-res vampire movies on a hand-held mobile device while waiting for a bus. But that’s what human beings want, and that’s what human beings need…. The Internet surprised us with its mass adoption.”

In Kitten Clone’s second section, “PRESENT”, Coupland interviews Alcatel-Lucent employees from Calais and Paris in France, each possessing a humility and wisdom similar to Hofmann’s back in Jersey. In the book’s final section, a trek to China to see firsthand the future of telecommunications, Coupland exposes the dichotomy between the humble architects of Alcatel-Lucent and their users’ technologically manic race towards the future. It’s in those quiet offices, the ones missing slick glass conference rooms and amoebic modular furniture, where Kitten Clone clicks into place.

Kitten Clone is the kind of book that could have been published online and taken full advantage of a rigorous, multimedia digitizing. Coupland writes in a spastic, data-overloaded manner that would transform remarkably well with pop-ups, embedded videos on autoplay, or riddled with hyperlinks to catch each of Coupland’s pop culture references. It would not feel wrong to read Coupland’s text on a phone, in some deluxe app with a stylish interface and push notifications. Coupland’s tangents flow with the ease of a mindless mouse click, only to be slapped central with the author’s yearning for focus. It’s a calculated cry for clarity, and all very much intended: Coupland at once investigates the state of our internet-addicted collective conscious and that digital undertow that could slowly consume its users. “I wanted [Kitten Clone] to mirror the way we look for information on the Internet,” he writes, “its random links, its chance encounters, and its happy coincidences.” Facts are Googled and Wikied, rapturously so, reveling in information’s immediacy.

Visual Editions’ role in all this is paramount, and their design for Kitten Clone creates a mesmerizing experience and ultimately a triumphant publication. The publisher’s primary goal is to create books that remind the reader of the importance of form, the book as an object, and so Kitten Clone is unplugged. The clutter and noise of Kitten Clone is ultimately quieted, as if conceived in the Murray Hill anechoic chamber of Bell Labs. Coupland’s techno-static is diffused with wide margins and a nontraditional trim-size, interspersed with photo-illustrated segments by Olivia Arthur that recall the placement of plates in an old reference book, ribboned in multiple spreads every forty-or-so pages of text. These photographs exemplify the simplicity of Alcatel-Lucent: a corkboard, an office chair, a khaki-clad older man running some wires across a room. The shots are wildly potent in their near-boredom, and complicatedly so, considering much of the world’s futurism is contingent upon their subjects’ involvement.

The fine design and thematic pacing of Kitten Clone redeem some of Coupland’s authorial missteps. Besides an almost Kafka-esque treatment of Alcatel-Lucent’s mission, a fictional character named Alphonse Garreau makes appearances in a number of different time periods to illuminate how information was transmitted throughout history. It’s a cute touch to see how cat pictures might have been shared in the 1870s or in 2245, but the lightness of this Garreau daydream cheapens many of Coupland’s clarity about technology and the future. “Right now, half of humanity – the younger half – believes the Internet is reality,” Coupland muses. “And the other half? We simply haven’t yet reached the point where we, too, accept that the Internet is the real world. But we will.” It’s an intimidating sentiment, but Coupland, Arthur, and Visual Editions have prepared us for this shift with Kitten Clone: it is a finely crafted book of conceptual acceptance and inherent resistance.

Jeff Alford is a critic and book collector based in Brooklyn and is also the writer of the rare books and small press blog www.theoxenofthesun.com.