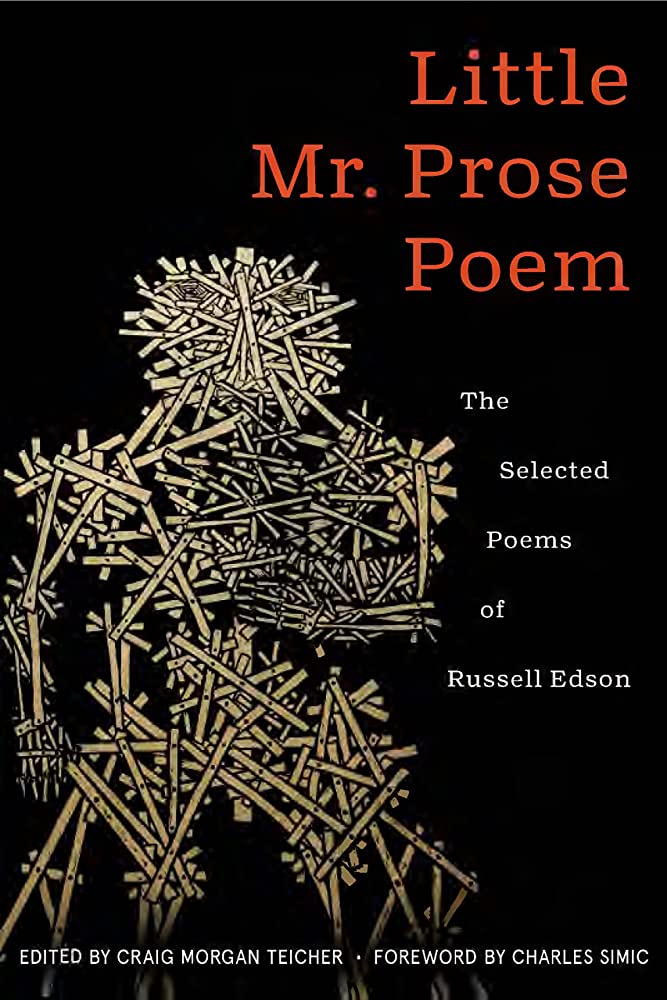

Highlighting the iconic prose poems of one of the masters of the genre, Little Mr. Prose Poem: The Selected Poems of Russell Edson culls 50 years of the poet’s works, including poems from The Very Thing That Happens (1964), What A Man Can See (1969), The Child of an Equestrian (1973), The Clam Theatre (1973), The Intuitive Journey (1976), The Reason Why The Closet Man Is Never Sad (1977), The Wounded Breakfast (1985), The Tormented Mirror (2001), The Roosters Wife (2005), and See Jack (2009).

Those familiar with Edson’s absurdist prose poetry will be pleased by the works editor Craig Morgan Teicher has chosen. Those unfamiliar will happily be welcomed to the fascinating world Edson created and recreated over the years. His work reveals a spectrum of human emotion, disconnection and miscommunication, ownership and imprisonment, paranoia and hysteria, so often homing in on our most “unevolved” ways—the crude, selfish, and primal.

Edson’s wild imagination is lived out through nameless characters that exist in a world where nothing is quite right. These characters don’t have what one might call “personal identities” in any confessional sense; instead, they are archetypes of age, gender, familial role, and animal: Wife, Husband, Woman, Man, Daughter, Baby, Son, even Monkey. This implied one dimensionality of the characters is eerie, and at times feels as though a reader is dealing with extraterrestrial beings pretending to be humans. There is an intentional disconnect between characters, logic, and “normal” emotional regulation and expression. What does connect these characters is that they almost always are messengers of some kind of tragedy.

In the poem “Ape,” for instance, Father is sick of eating the same dinner Mother cooks every night: cooked ape. This sets off an argument between Mother and Father, which leads Mother to think Father is accusing her of having sex with animal, then cooking it and making Father eat it, thus destroying the evidence of her infidelity. The characters’ communication styles feel like that of a drunken argument: “Father, how dare you insinuate that I see the ape as anything more than simple meat, screamed mother. Well, what’s with the ribbon tied in a bow on its privates? screamed father.” (44)

Sometimes referred to as neo-surrealism, the world Edson creates challenges the laws of the universe as we know them. His poems vary in bizarreness, with some maintaining a sense of structure and logic, allowing for some things to be off. In “Dismissed Without a Kiss” the cow takes off her horns, hooves, and milk bag to get comfortable before bed, and the farmer becomes upset with the cow for dismissing him without a kiss. In other poems, the English language feels torqued beyond its high-concept premises, as in “Dream Man” where the style feels akin to Gertrude Stein’s: “An apple is very cherry bigger, it is very something the same. And dream man said he will do dreams, He will do boxes—Now can you hide there, yes you can. And the clock which can go tick.” (31)

While Edson’s work can feel chaotic, it never lacks directness. He may lean into surrealism, but the poem’s reality is always grounded in the emotion of the characters who feel in extremes of anger, greed, passion, and paranoia. Drama is created here in unexpected and eccentric ways, which can feel like modern fables that sometimes dance around meaning. The woman who becomes a bed may be a depressive, or the man who is followed home by a park bench may be homeless, and the toilet that demands to be loved but is rejected implies an actual person who feels rejected, unlovable, and disgusting. The narration of the prose is usually dry, morbid in humor, with few moments of romanticization. In “When the Ceiling Cries”: “A mother tosses her infant so that it hits the ceiling. Father says, why are you doing that to the ceiling?” The humor is often surprising and full of movement—jolting, mocking, dark.

On the whole, Little Mr. Prose Poems feels moody. There is a blankness, even in the most animated of moments, that is eerie. The hysteric and animalistic nature of his characters creates a facet of the mood that is raw and freakish: a baby throwing up his brain in colic; an old man who vomits metal, a man executing his own leg because he only has one boot. This eeriness is also enhanced in a lack of conventional imagery and setting. We are often in liminal spaces, the preferred playground for these characters.

Perhaps the best way to convey Edson’s work is to cite an emblematic poem in full. Here is an early poem, “A Stone is Nobody’s,” from The Very Thing That Happens:

A man ambushed a stone. Caught it. Made it a prisoner. Put it in a dark room and stood guard over it for the rest of his life. His mother asked why. He said, because it’s held captive, because it is captured. Look, the stone is asleep, she said, it does not know whether it’s in a garden or not. Eternity and the stone are mother and daughter; it is you who are getting old. The stone is only sleeping. But I caught it, mother, it is mine by conquest, he said. A stone is nobody’s, not even its own. It is you who are conquered; you are minding the prisoner, which is yourself, because you are afraid to go out, she said. Yes yes, I am afraid, because you have never loved me, he said. Which is true, because you have always been to me as the stone is to you, she said. (26)

The turn at the end of the poem feels quite devastating. It seems the mother has owned her son just as he has owned the stone. The poem makes us return to its beginning and ask, What is the relationship, quite literally, between ownership and love? As in so many of Edson’s poems, there is a different kind of “honesty”—a harsh tenderness that reminds us that the concept of “honesty” in poetry doesn’t always have to be tethered to “authenticity” of experience.

Imagination does not merely serve as a cornerstone in Edson’s work, but inhabits each and every building block of it. Even if some of the poems were written half a century ago, they still feel visionary, both freakish and freeing, today. If the subject matter can be discomfiting, there’s a secret joy to be had from it. The world of these poems offers catharsis and transcendence, and illustrates life’s brutal nature, which, in turn, exposes the contrary: “Suddenly, everything is beautiful. He begins to cry.” (“The Marionettes of Distant Masters”).

Ruby Zlotkowski is a junior at Loyola University New Orleans, studying English Writing and Graphic Design. She moved from her home city of Chicago to New Orleans in 2020, and immediately fell in love with its trees, cats, and hot sun. She enjoys reading and writing work regarding nature and eclectic spirituality.