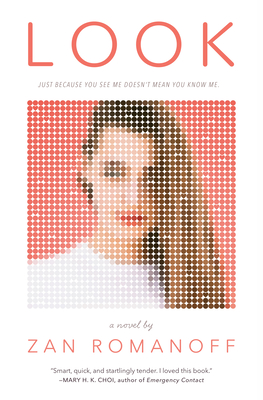

Look by Zan Romanaff. Dial Books, 2020. $17.99, 366 pages.

Women experience objectification in film. You’re probably rolling your eyes and thinking, Of course. So many forms of media treat women as objects, most of us have known about it forever, none of this is exactly new. However, Zan Romanoff’s achingly beautiful novel Look infuses this issue of objectification with a sense of energetic, contemporary self-discovery. Look delves into the life of seventeen year old social media celebrity, Lulu Shapiro. Amidst a reputation-threatening scandal, Lulu meets a girl named Cass who doesn’t quite belong to Lulu’s world of wealthy elite Los Angeles private school kids. As Lulu and Cass’s relationship deepens, they discover mutual fascinations with art-making, L.A. history, cinema, and other interests that teem with women who are sick of being looked at the wrong way. Look reminds us that there is always a young woman out there in this great, big, image saturated world who’s learning that the act of being seen is never neutral.

The novel opens as Lulu secludes herself in a bathroom during a high school rager. It’s the kind of party Lulu secretly loathes but always attends because aren’t you supposed to accept every invitation to every cool party? She films pretty footage of herself to share over social media while simultaneously judging herself for hiding: “she should go downstairs and be social and stop sitting alone like a weirdo. She should go back and pretend everything is normal, so that at some point, everything will be normal again.”

Lulu’s life has been hard, lately. Over the summer, she accidentally outed herself as bisexual, though she’s pretty insistent that labels makes her uncomfortable: “‘I don’t like any of the words. Queer. Pan. They don’t feel like me. Like they’re mine.’” Everyone in school keeps gossiping about Lulu’s love life and this attention amputates Lulu from her own sexuality: instead of actually disentangling and examining her feelings, she obsesses over how it all looks. She’s convinced that her outing seemed performative, silly, fake, and desperate: “Everyone knew that Lulu Shapiro would do anything for attention. Kissing girls certainly belonged in the category of anything.” Romanoff delves into how much this scandal intersects with Lulu’s constant sense of displacement: instead of confronting the gossip, the rumors, or the truth, Lulu keeps snapping the same old pretty selfies.

But, back to the rager: while hiding in the bathroom, Lulu meets Cass. Cass is a shy girl who doesn’t seem to care how she’s looked at: “Lulu can’t decide whether Cass is trying and kind of failing, or if maybe she doesn’t even know she should be trying.” Before Lulu can make up her mind, Cass steals Lulu from the party and whisks her away to a teen-run hotel hideout where phones are not allowed. The owner of the hotel, Ryan, hates social media, especially the website Flash (a sort of Snapchat and Instagram hybrid). Lulu surprises herself by gravitating towards this phone-less ideology, particularly because “…Ryan’s not wrong about how she uses [Flash], especially lately: to make her life look beautiful and interesting, especially when she’s lonely, or uncertain, or bored.” Over the course of the novel, Ryan’s phone-free hotel becomes a kind of oasis of vulnerability for Lulu.

Romanaff’s decision to set up a space that separates Lulu from her phone is integral to the narrative. Lulu’s got 10,000 Flash followers, all of whom slobber over a highly sanitized, glamorized version of Lulu’s life. Throughout the text, Romanoff uses these followers to remind Lulu how she’s supposed to be acting. If Lulu stops updating her Flash, her followers harangue her: “Lulu has actually been pretty lazy about updating her Flash story lately, so lazy that she got a couple of messages yesterday asking what was up. She feels self-conscious and then self conscious about being self conscious. She knows she shouldn’t care what these people think of her.” In response to her followers’ complaints, she stages and films Flash stories typical of a popular party girl so that thousands of strangers will not realize that Lulu has no clue how to manage desire, loneliness, or her frustration with her own reputation: “it makes her feel better about everything in her life right now, to know that at least it still looks like she’s living the way she always has.”

When Romanoff forces Lulu to ignore these followers, Lulu finally has to confront how she’s not living the way she always has. Lulu’s aware that she likes kissing girls, for instance, and that–in front of her followers–she somehow construes her own desire as a bid for attention. When Lulu’s not thinking of her followers, however, she feels this attraction instead of viewing the attraction from a distance, through a screen. She stops thinking of herself as “Lulu Shapiro [who] would do anything for attention.” Instead, she starts thinking about how good it feels to hang out with Cass.

As a self-described “indoor kid,” Cass isn’t Lulu’s typical type: Cass unashamedly hates Flash and is bad at parties. She’s from a middle class background and can provide some rare insight into the suffocating aspects of Lulu’s privileged ecosystem: “‘..normal isn’t how everyone knows everyone, how you’re all always talking about how we met through JTD, The Center…that summer program in Cambridge.” Cass’s infectious honesty allows Lulu to be vulnerable: “[Lulu] can feel the way…Cass is peeling her apart in onionskin layers, so fine Lulu barely notices the process of being bared.” Romanoff uses Cass to push Lulu’s gaze both inward, towards the experience of processing emotions.

Though a budding relationship with Cass is integral to Lulu’s awakening, Romanoff does not make the mistake of resting the total burden of Lulu’s growing consciousness on Cass’s shoulders. Instead, both girls begin to engage in new types of media and culture, specifically an ancient fairytale about murdered women, Bluebeard. Lulu and Cass watch a silent film version of the story, read a literary adaptation, and delve into a particularly well-rendered, You Must Remember This-esque podcast series on the fable. Over the course of the book, Cass and Lulu debate the meaning of the fairytale and how it demonstrates the power women lack. Cass insists that the themes in the murderous Bluebeard story are too resonant and real to simply be the stuff of fairytales: “‘[It’s] a myth…It’s like the thing at The Hotel that I was talking about–about what happens to beautiful women. Not a curse. Just a thing.’”

Gradually, Lulu reexamines the idea of beautiful women acting on screen; over the course of the book, she acknowledges how often they’re being manipulated by off-screen men. Lulu knits this marginalization to her own feeling of internal misery that she ignores when she posts fun Flashes. Lulu, upon understanding the unfairness of misogyny for the first time, rails against it. Poignantly, she doesn’t accept any of her new realizations with perfect poise. She screams, she snaps at her mother and sister, she blows off some of her friends, and she’s not always perfectly kind to Cass. Lulu has a lot of work to do on herself, but she knows that she can’t go back to smiling through it all on Flash. It’s exciting and invigorating to witness Lulu reframe her own life so that she is not acting as a pliant object on a screen, controlled by what her followers think she should be doing. Instead, Lulu pushes her passion towards other, more surprising outlets, while deciding that, “The world is indifferent to her, and that means she can do whatever she wants as long as she’s in it.”

Diana Valenzuela is an Oakland-born, New Orleans-based author. She cares about red eye shadow, Lifetime Original movies, and Britney Spears. Her work has appeared in The Millions and PULP Magazine.