She wasn’t a painter. This was one of my first thoughts while looking at the works on view in Louise Bourgeois: Paintings at The New Orleans Museum of Art. Later I read in ARTnews this quote by Claire Davies, associate curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who organized the exhibition:

“She never went back to painting. She continued to draw so she was still very much invested in kind of putting pen on paper, but she didn’t take up a paintbrush again after 1949. That kind of begs the question: why? I went into the exhibition hoping to answer that question, but I came away convinced that it’s not really possible to answer it definitively.”

I can’t definitively answer the question of why Louise Bourgeois abandoned painting, but I have an idea. I don’t think she was really a painter to begin with. When I use the word painter, I don’t mean an artist who uses paint; I mean an artist for whom the medium itself is imbued with a unique power and significance. This kind of painter yields control of the outcome to the material and the spontaneous gesture. Spontaneity is recorded in the characteristics of the brushstrokes. The term “a painter’s painter” is sometimes used to describe painters whose paintings are as much about paint itself as they are about the subject. When I thought to myself that Louise Bourgeois was not a painter, I was thinking of this kind of painter, an artist for whom paint is a faith-based practice. Louise Bourgeois used paint but didn’t worship it.

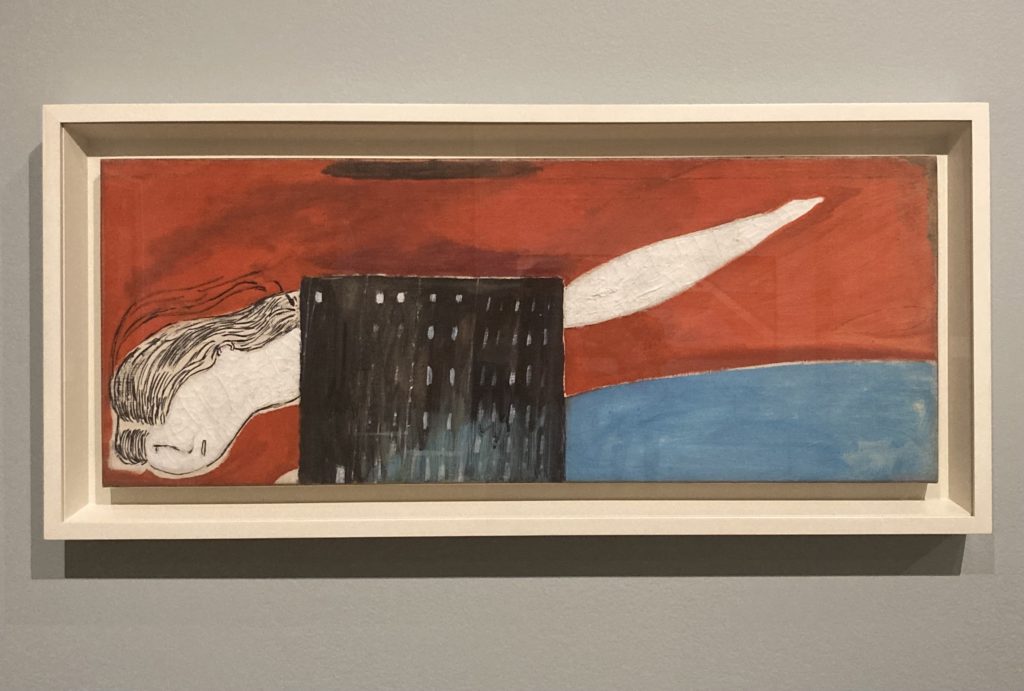

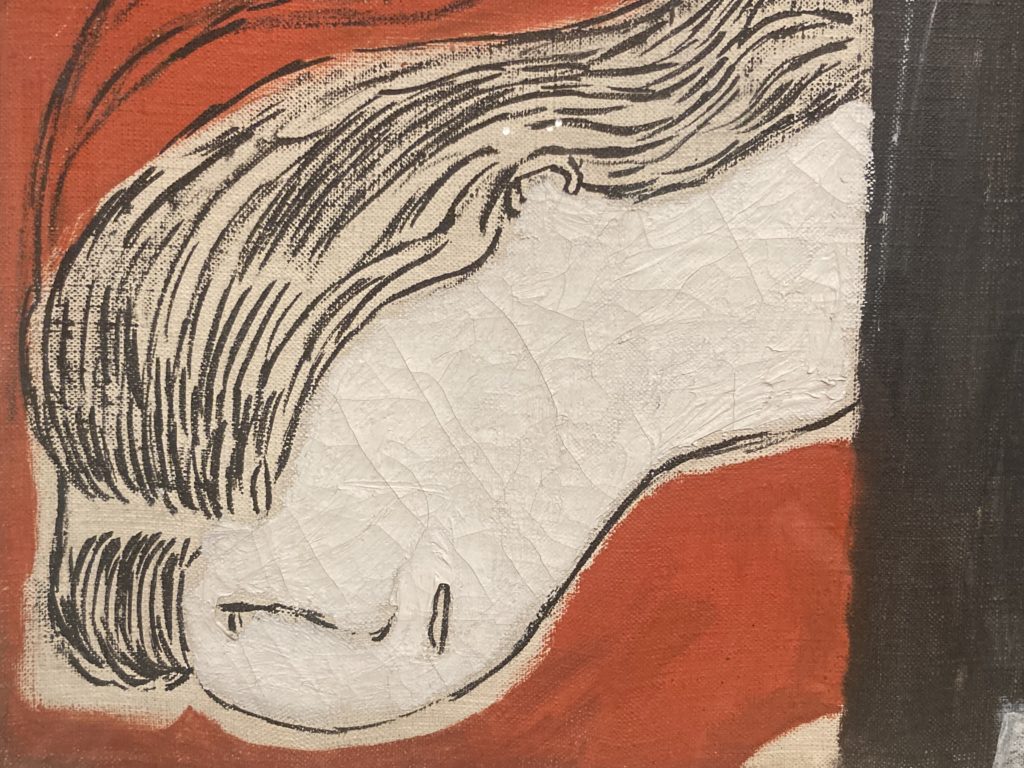

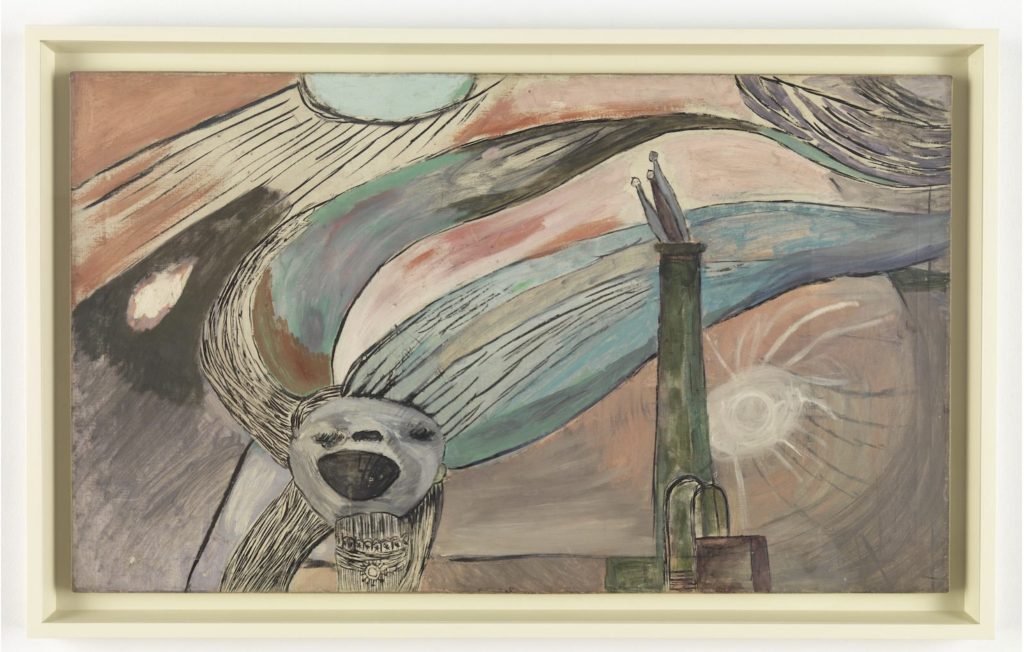

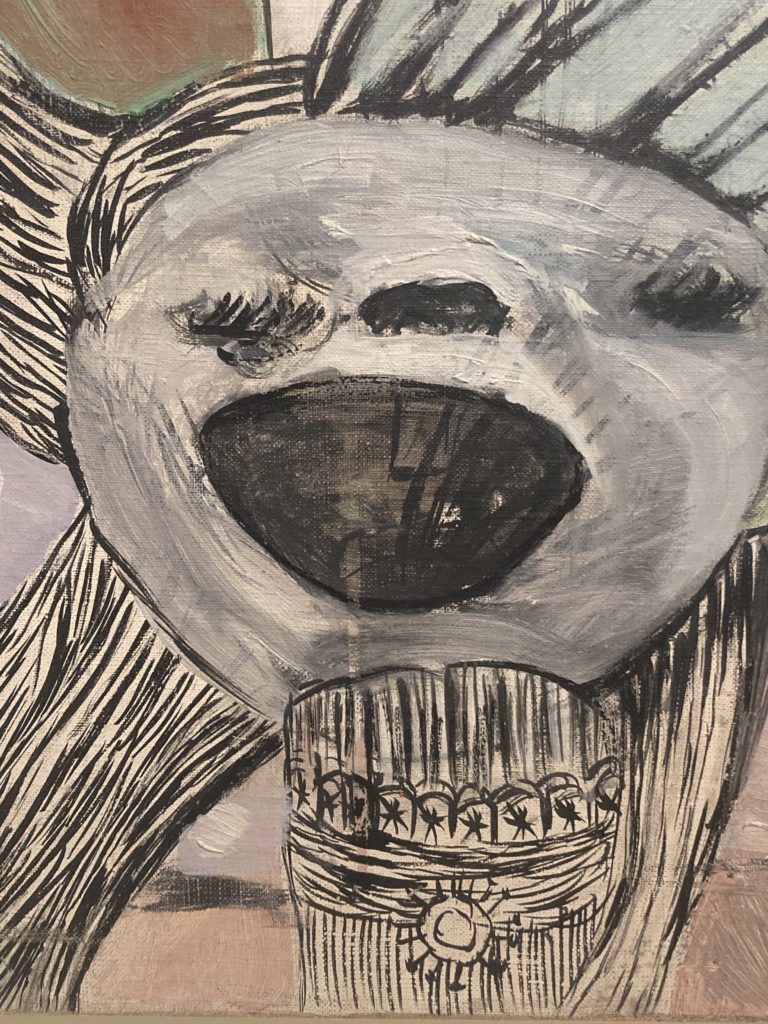

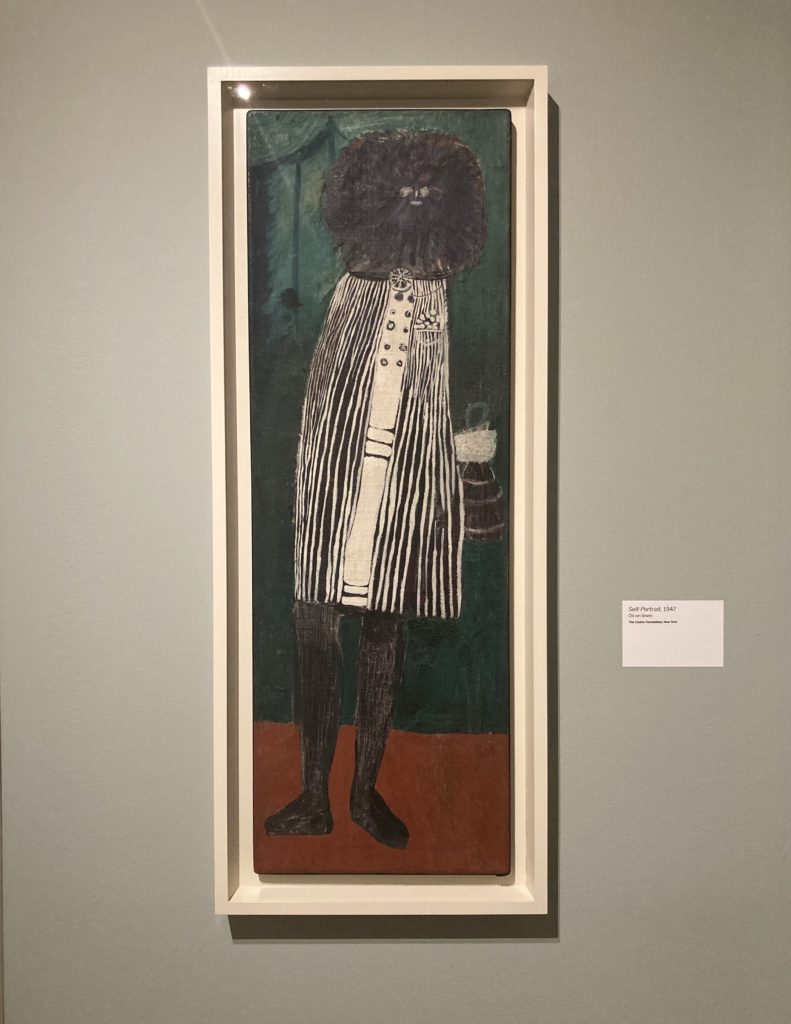

The way I see it, Louise Bourgeois mostly used painting as a conventional space and practice for developing visual ideas. She mostly used paint to draw. She also used paint in flat areas of color to distinguish one forms from another. She drew lines with fluid paint using small brushes. She scratched drawn lines into paint. In several paintings, she chose to keep the underdrawing visible rather than painting over it. The power in these paintings rests not in the use of paint but in the elements that are drawn, articulated with lines. The fact that most of the works in the show are being glass (as drawings almost always are) so that the surface and vibe of paint is encased, also encourages one to read them as drawings.

There isn’t a hard line between drawing and painting. Drawing suggests dry media and paint suggests fluidity, but an artist can manipulate media in either direction with water, oil, solvents or the absence of these. When an artist draws, the artist controls the medium with little physical resistance. The struggle in drawing is located in or between the mind, the eye and the hand. A painter’s struggle is different. A painter’s struggle is located somewhere in or between the body and the material. The painter’s struggle is existential. And then there is sculpture. Louise Bourgeois is most widely known for her sculptures. A drawing or painting can suggest form, create the illusion of it. But sculpture is form. In the later paintings of Louise Bourgeois, there are shapes that want to be physical forms, vertical shapes that actually look like sculptures.

I cannot say what external forces moved the artist to work with paint in the first place or to abandon it for good. But I know the lure of convention. Painting, in addition to being a faith practice for some, is also a convention, an established format and an available course of study. Painting has been the first stop on many artists’ journeys to other media. I wonder if Louise Bourgeois had set out to be a sculptor in the traditional sense, what she would have made of those conventions and of that context. I loved seeing these paintings, even though they were not “painter’s paintings.” Maybe Louise Bourgeois found her voice within the framework of painting, but from what I observe, she wasn’t inclined to remain there. This is not a definitive answer to the question of why she abandoned painting. Then again, the power of her sculptures and drawings may be the only answer we need.