Part 1: New Orleans to Houston

12:30 p.m.: Lunch

In the four years I’ve spent in New Orleans I’d never had a Lucky Dog (this is a tourist staple, like the Dodger Dog in LA or Spumoni Gardens pizza in Brooklyn). While I worked in the French Quarter nearly every weekend, the dank, hefty atmosphere never once made me want a hot dog. So it was strange to walk through concourse B of Louis Armstrong International Airport and suddenly see a hot dog shaped cart with yellow and red letters on the side—the same as the carts parked on Bourbon or Royal Street commissioned to down-and-outs, ex-cons and recovering or relapsing addicts. Of course, not all of the Lucky Dog employees are so dejected. The woman manning the cart in the terminal is just one of many people who found employment at the airport.

Maybe it’s my confidence in this woman; maybe it’s the circulated air that has me feeling so bold. This Lucky Dog stand, so out of its element, is finally in the perfect environment for me to wake up and smell the beef.

At $4.50, the Lucky Dog inhabits a special economic niche, pushing the limit of what French Quarter tourists will pay for a hot dog, but delighting the hearts of men and women waylaid in an airport. This is a steal. Enough food to sustain me for the four-hour trip from New Orleans to Los Angeles (with a layover in Houston), where an old friend is waiting so we can drive home and revisit our old beach town haunts.

Good luck hasn’t defined my time in New Orleans. Robbery, gunpoint theft, infestations, infections. These words paint a more accurate depiction. As I prepare to fly back to California, I’m counting on this hot dog to turn my luck around.

I walk down the concourse to my gate and pick a seat. Ketchup and mustard stain my Lucky Dog’s paper tray, and I angle the hot dog about forty-five degrees so that the juice and condiments don’t drip on the carpet. The Lucky Dog is plump and juicy. It’s not like ballpark hot dogs, or county fair hot dogs. It’s not the type of hot dog that breaks your heart when you realize that it’s all bun and no cattle. Two cows died for this hot dog. It hangs a precarious inch over either side.

I’ve hardly finished it when a woman announces over the intercom that flight 4579 from New Orleans to Houston has been delayed, and that the gate has changed. I’ve still got hot dog in my mouth as I stand up and arrange my bags. But then suddenly from the same god-like place that the announcement came from, the distinct sound of a fart reverberates through the concourse. I turn to the information desk at our former gate and see that the woman had held the phone down by her waist. She snaps the phone back on the receiver as she tries to casually look side to side, assessing whether her toot has been noticed.

It has.

1:30 p.m.: Boarding

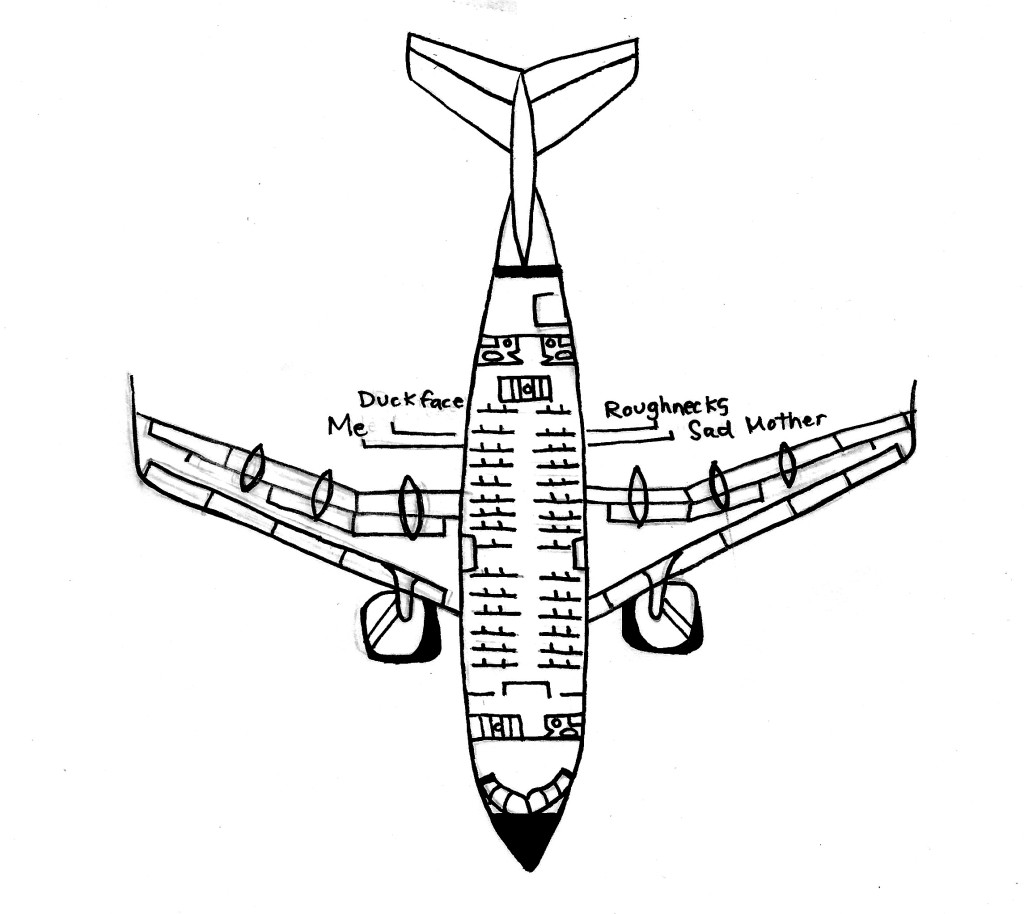

Southwest Airline’s find-your-own-seat policy suits me fine, and I’m at a window towards the rear, close to the wing. I’ve only vaguely paid attention to the other people boarding the flight with me. All I really notice is that there’s a substantial number of burly men. Most of them have chosen to sit in the back as well.

A middle-aged blonde woman and her probably fifteen year-old daughter search for acceptable seats. The daughter wants to sit across the aisle away from her mother, and a minor skirmish erupts between the forces of maternal dominance and teenage rebellion. This round goes to the mother, and the daughter slumps into the seat beside me. The daughter immediately pulls out her cellphone and snaps several selfies, and ohmigod nobody understands.

Snapchat. Twitter. Facebook. Tumblr. Instagram. Vine. Repeat.

Her duck face is mean.

The crew is sassy. The burly men play it up. A stocky redheaded man flirts with a flight attendant. He fires volleys. She masterfully returns. But she hushes his advances, grabbing her microphone and beginning the “Good afternoon passengers aboard flight 4579…” rigamarole. People chat and I get my headphones out, plug them into my phone and tighten my seatbelt, wondering how much this strap is really going to help if we nosedive somewhere in the Gulf of Mexico or along the coast of Galveston.

We taxi out onto the runway. This is the exciting part. The part where you hear the engines begin to build power to a barbaric yawp. Other planes take off and other planes land. I lean my forehead against the window and feel the plane vibrate. The mechanical bits of the wing adjust their angle for takeoff. I brace for the slingshot feeling of careening down the runway, and that exact moment when the plane achieves lift, and it seems like the only possible ending is for it to abruptly bottom out. But even that doesn’t come. The engines wind down and the pilot informs us that we’re delayed by bad weather in Houston. “We’ll sit here for a minute,” he says in that gravelly voice they probably teach you in flight school. “And the uhhhhhhh next update should come from the weather service in either twenty minutes or an hour.”

Twenty minutes or an hour.

Airports and airplanes exemplify the relativity of time and space. We are told to “expect delays,” and we keep people on alert in various parts of the country, letting them know when we are finally actually about to take off, or when we they might reasonably expect for our plane to touch down on the other side. Or they can follow your path, a lengthening green line lead by an airplane icon, on FlightAware.com. Travel time can indeterminably expand or contract, and the minutes within the hours vary according to how (im)patient the waiting person has decided to be. The degree of patience, and by extension the expanse of time, is often mitigated by socio-economic status: it’s easier to be patient in the Delta Sky Club, sipping complimentary martinis; or here, in the Southwest 737, perhaps if your mortgage payment is not in limbo for next month.

But the airlines both play up and play down the differences in class status among their fliers. In the initial stages of delay, a full plane seems to be a singular unit. We are, as a group, an accumulation of passengers just trying to get somewhere as soon as possible. I pull out a book, but I’ve never had an easy time reading on planes, and the creeping minutes fracture the unity of the passenger-body in a way that’s so fascinating that James Baldwin will have to wait.

2:30 p.m.: Factions

The burly men seem perfectly comfortable stuck on a runway. They’re talking to each other about where they’ve come from and where they’re going (Saudi Arabia, the Gulf of Mexico, Singapore). But really they’re all coming from the exact same place: oil rigs. No matter how they got to New Orleans, they all spent the last three weeks hustling their asses off on floating cities. Some of them have matching shirts that say “off-shore athletics.” I imagine little-league type events with older rough-necks cheering on their younger, fitter counterparts. They don’t give two shits about the delay. Not only is their flight paid for, but they seem to be getting paid for their time.

The mother and daughter seated beside me speak in low hushed voices, hurriedly clicking the digital keyboards on their phones. Mother calls the airline to complain. The daughter tweets and texts. They are part of the impatient faction, though not so much because they’ve got important business or because of some time-to-money conversion ratio. They seem to be from a class of people who are just unaccustomed to waiting—or at the very least, easily put out by it. The type of people who get indignant stank-faces when a restaurant host says the wait will be fifteen minutes. “But we called ahead.” “Ma’am, the Hard Rock Café doesn’t take reservations.” Still, it’s absurd for a plane to be delayed by nearly two hours for a flight that’s only going to take forty-five minutes. The mother has honed her craft, which is speaking tersely on her cell-phone as she ignores the answers to her questions and simply tries to see how high up the chain of command she can reach.

“Is your supervisor available?”

“I’d like to speak to your manager.”

“Who’s in charge of this department?”

“Get me the president.”

As for the daughter: 140 characters and all of them cryptic.

And sure, none of us really want to be on this plane any longer than we have to. As the pilot announces on the twenty-minute mark that the weather is just awful and he’s so sorry but we’re going to pull into the next available gate, I admit that even my anthropological heart sinks. I’m aligned with the faction of those in no hurry to get home, except that I’m putting someone out on the other side, who is on standby to pick me up. Someone who I want to drink beer on the beach with. This is the trip home. The one-way ticket that ends my time in New Orleans, my undergraduate education, and all of the heartbreak and happiness and exhilaration and exhaustion of my early twenties. That’s not over until I land on the other side.

Question: What is the most Lucky Dogs a Person has ever eaten at one time?

Answer: An unidentified French Quarter Policeman allegedly ate thirty-two during Mardi Gras, 1998.

The Lucky Dog website is spare, but it’s enough to keep me occupied for a moment as we sit at our new gate. In fifty years, the company has sold over twenty-one million hot dogs. They claim to satisfy the social eating craze known as “grazing,” or eating on the run.

“A Lucky Dog in one hand, a soft drink in the other. We have proven to be highly successful in airports, casinos, malls, sport stadiums, and numerous other heavily trafficked areas where service and speed are at a premium.”

They aren’t serving Lucky Dogs on the plane. Though they probably could. The cost to have an event catered by Lucky Dogs starts at exactly $747.00.

2:30-ish: Initial De-Boarding

Until a few years ago, there was no strict rule on how long an airline could keep passengers on a plane on the runway. Now, federal law requires that passengers be allowed off of a plane if the wait is going to be more than three hours. In our case, we haven’t hit that limit, but the weather in Houston is indeterminately sketchy, so we have pulled back into our gate, and anyone who wants to can get off of the plane. But because we could get a green light from air traffic control at any minute, we are urged not to stray far. As a result, the mean people, the anxious people, the aggravated, irritated, hurried persons get off the plane as soon as they get the go-ahead from the captain and crew. The rest of us would rather not give up our seats. We’ve settled in. We have faith in the weather and mainly we just don’t think it’s necessary to go through the whole boarding process again.

Most of the roughnecks are still in their seats. The exceptions are the ones who need a drink (need it like you and I need water, oxygen and wi-fi). Smokers are in a more delicate situation. Louis Armstrong International doesn’t have a designated smoking section beyond the security checkpoint. The smoker’s only option is to leave the airport and smoke outside, and then they’d have to go back through security. So instead, fingers are tapping, throats are clearing, sighs are becoming increasingly exasperated.

Across the aisle, a woman with an e-reader has begun the where are you going, where have you been routine. People coming from as far as Singapore and Bangladesh fascinate her. Her phone is about to die, and the man from Singapore has lent her his wireless charger, which fascinates her in the same way people along the trade routes of the Indian Ocean were intrigued by the craftsmanship of Chinese coins. The wireless charger, to her, has come from somewhere far far away.

“Best Buy,” the man from Singapore informs her, bursting her bubble of exoticism. She then tells me that she’s going to Long Beach, and that “it looks like we’re in this together.” She came to New Orleans for a custody hearing regarding her fourteen-year-old daughter. The daughter is in the custody of her “awful misogynistic ex-husband.” Her big eyes well up with tears as she shows me pictures on her phone. Luck wasn’t on her side this time around, and she’s going home alone. Now she’ll have to decide whether to appeal her case to the Supreme Court of Louisiana, a decision which will be weighed against the cost of lawyers, travel, and her own lost wages. And as much as I sympathize, I realize that I really am in this with her for the long haul. She repeats the story to every person she speaks to, going into greater and greater detail to the point where we can no longer sympathize, really. It’s enough to feel like we’ve been inserted into her family crisis. All I can be thankful for is that her daughter is not on the plane, because if she was, she would be cradling her head in her hands, trying to press herself through the little window and as far away from her mother as possible. This woman is perfectly nice and worthy of our respect, but in her attempt to reach out and find human dignity and compassion after all of the hate of ex-love and split families and all the cold hard impartiality of the courts and judges and all the expense of lawyers, she is scaring us. She punctuates each sad clause with a nervous laugh.

The mother and daughter who were sitting next to me left the plane at their first chance, and from the sound of it, they were not going to come back. So I’ve got three seats to myself. Every thirty minutes a barrage of ringtones, almost in sync, signal that “This is Southwest Airlines calling with a flight status update…” and then different groups accumulate in different areas, circling around the individuals who signed up for alerts. Most of the ringtones are iPhone sounds, and it’s moments like this when one has to acknowledge Apple’s impressive market saturation, even in thoroughly coach environments such as Southwest creates.

6:00 p.m.: Inconveniences and Amenities

My Macbook is open on the tray. My seat-back is reclined, and not only has the flight attendant served me soda and peanuts and pretzels, but she also insists she take back the coffee she made for me because she doesn’t feel like it’s hot enough. She comes back moments later with a fresh steaming cup. All the while she’s playfully sparring with the burly redheaded roughneck, who it turns out is from outside of Houston, and whose name is Brad.

Brad exudes Texas. Even his body-type suggests the lone-star state: a broad chest and thick arms supported by short, slender legs, with a square-shaped head. He’s the guy at the bar, or the kegger, or the barbecue, whose personality is so imbued with braggadocio and machismo that it somehow manages to leap past annoying and into the realm of entertaining. He is a Texas self-parody. He’s not George W. Bush. He’s Will Ferrel as Bush. His persona reminds me to call my father, who has worked in the oil fields all his life, and made the economic decision early on to transfer from custom wrought iron to oil-piping. I don’t want the guys on the plane to hear me calling them roughnecks so I tell my dad that I’m here with a bunch of offshore-men.

“There’s a lot of money in being a roughneck,” Dad says.

“So I hear.”

“Just don’t play poker with any of ‘em.”

I hang up the phone. Somewhere behind me the flight attendant says “Screw it. I’m sitting down.” Even as we wait, the flight attendants are apparently not supposed to sit except for takeoff, landing and turbulence. The lives of flight attendants and roughnecks peculiarly intersect. Both professions demand extensive time away from home, life in temporary spaces, and arduous conditions. Brad points out these similarities, but the big difference is pay. When Brad started out, his salary was $105,000 a year. Flight attendants start around $19,000, and the median wage is around $36,000. “Plus,” the flight attendant says, “We pay about $100 a month for parking.”

“This is Southwest Airlines calling with a flight status update…”

Each update moves our departure time back another thirty minutes. We are Achilles, racing towards the slowly advancing tortoise, with the gap in between getting increasingly smaller, but never closing.

I could use another Lucky Dog.

Flight attendants have these neat hand-held fans. We’re not getting any air because the engines are turned off and ipso facto so is the air conditioning. I’ve unbuttoned my shirt and revealed to the world my undershirt, sweat-stained in the front. Those that have newspapers have turned them into their own fans. The plane cooks. Earlier, a passenger had attempted to stow an ice-chest full of fish in the overhead compartment. But he was caught because the chest was leaking cold fish-water onto everyone else’s luggage. The air is slightly fishy now. But despite the fish-stank, we’re all hungry for non-complimentary foods, yet so certain are we that the plane will eventually move that we don’t really want to risk de-boarding so late in the game. Brad suggests cooking the fish on the coffee maker.

All this talk of food has the roughnecks going on about the catering aboard their respective rigs. One of them came off a rig named The Spirit, which in the last two years has gone from the Gulf of Mexico to Indonesia, and is now on its way to West Africa. A company called Arcs caters it, and all of the roughnecks agree that Arcs does a damn good job.

6:45 p.m.: Re-boarding

We’ve got the green light. Passengers have re-boarded, and we’ve made room for some other people who have faced cancellations. The flight is full. We taxi out to the runway once again, and this time I really do feel the excitement. People applaud. The engines to build power.

Everyone is happy to finally begin our journey. But we end up sitting for a long while. I watch at least five planes take off.

7:00 p.m.: Re-fueling

In order to avoid bad weather, the navigator has calculated a newer, longer route. Unfortunately, this means we have to return to a gate to re-fuel.

Planes don’t typically completely fuel up. They load just enough to get to the destination, plus maybe an hour of fuel to be safe. The lighter the plane, the better the fuel economy.

Turns out we had enough fuel.

7:15 p.m.: Take-off

As we ascend, lake Pontchartrain glimmers in the lowering sun. The Causeway’s two parallel lines cut across the water far beyond my field of vision. Its shoreline is dotted with fishing camps, and we’re still low enough to see a few boats skimming its surface. Along the cut-banks of the Mississippi, chemical plants spew steam and pump hot, chemically potent water into the river. The toxic water flows past the French quarter and underneath the West Bank Bridge. Then New Orleans is gone.

We fly over the bayous. The marsh is here and there lacerated with keyhole shaped gashes from a hundred years of oil exploration. Bald cypress, tupelo gum, live oaks, cycads, marsh grass, and alligators, egrets, mosquitos and bullfrogs creeping through them. The turbine engine’s whir replaces the cicada’s hum. We are now out over the brown-blue of the Gulf Coast.

For a while, Brad the Burly Redhead has the excited spastic head movements of a cocker spaniel. With the new route, the distraught mother wonders whether we’ll make it in forty-five minutes.

“Of course we’ll make it,” Brad replies. “This thing’s got a Hemi!”

But eventually Brad settles into place, and his eyelids lower until they’re at that not-quite asleep meditative point. The distraught mother has been staring at her Kindle for a long time, but it doesn’t seem like she’s reading. She’s probably calculating the ever-expanding distance between her and her daughter. Our flight attendant is buckled up, waiting for us to reach cruising altitude.

Flight is still such an irregular occurrence for me that I can’t peel my eyes away from the window. Far in the distance I can see one of the cumulonimbus clouds that we’re circumnavigating. Sometimes it looks like an anvil; sometimes it looks like an atom bomb. The turbulence keeps Brad awake. He tells me about his work.

According to him, they’ve recently discovered such a large cavern of oil in the Gulf that it rivals most anything found in Saudi Arabia. But it’s deep, and he doesn’t see why we make it so hard to get at that oil. From his point of view, I can’t really disagree. Increased production in the Gulf would probably bring a lot of high paying jobs to Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas. Still, the reason he even has the high paying job he currently has is because of one of the worst oil disasters in world history. Brad is a deep-sea engineer. And his job is basically to lay the foundations for deep-water rigs. He is responsible for all of the safety precautions—the shut off valves, the blowout preventers, and the immense concrete structures that encase the pipe. Basically, if it was mentioned on the news after the Deep-Water Horizon spill, he is responsible for making sure that it’s functional.

The demand for deep-sea engineers skyrocketed after the Macondo explosion. As much as we villainize British Petroleum, the fact is that nobody wants an oil platform to explode (the difference is that for BP’s then-CEO Tony Hayward, the crisis seemed to be one of plummeting dividends and bad PR; not one of human tragedy and irreparable damage to an endangered landscape and way of life). It only takes a microscopic pocket of gas coming up from a depth of ten-thousand feet below the surface to do the damage that we saw playing month after month on the news in 2010. That was the year I had moved out to New Orleans. My first experience of Louisiana’s way of coping with disaster was seeing residents decorate their homes with tar balls, oil covered pink flamingos, and signs that read FUBP. I couldn’t really believe that the jobs gained by deep-sea drilling would ever replace the jobs lost and damage done to the Gulf. The effects are still running up the ocean’s food chain in ways we won’t be able to comprehend for decades, probably even centuries. Other effects were clear and apparent. World-class restaurants shut down as oyster beds and shrimp catches were tainted and dwindled. Even as BP and other parties who were ruled responsible for damages continue to fight against paying back those who were harmed, there have been huge investments in bolstering safety precautions. Brad was in logistics at the time, and when the first waves of advancement were posted, he jumped at the opportunity to do more complex work, and to make up to $300,000 a year. Three years later, he’s on a plane with me, about to get his first 30k bonus.

As the daylight draws to an end, the Gulf teems with activity. Tankers and cargo ships crisscross each other in the vast expanse. There are more platforms than I can imagine.

“You wouldn’t believe how much work is out there,” Brad says. “I still remember my first flight to work. It was at night. My boss was sitting right next to me, and I asked him what city we were flying over, because of all the lights. He told me, ‘Hell, boy, that’s the goddamn Gulf of Mexico.’”

The god damned Gulf of Mexico.

8:00 p.m.: Descent

Galveston looks like an environmental disaster from the air. The sea wall attempts to protect the Island from the Gulf. All it’s done is kill the beaches on the seaside. There isn’t a granule of sand left outside the wall. Back behind it, things don’t actually look much better.

“There used to be so much land back there,” Brad says, pointing to a lagoon somewhere behind the wall. He explains that Hurricane Ike came through and just completely devastated the Island. But it wasn’t the hurricane. It was the wall, preventing the movement of sand from the sea to the shore to the back of the island. It’s hard to say from this height, but it looks like whole suburbs have been inundated in brackish water and left to erode with the rest of the island.

Galveston Island disappears and Houston comes into view. We hasten our descent, the landing gear deploys, and we touch down on the runway, cheering and applauding. Some people get to go home. Some still have many miles to go before I sleep.

Part 2: Houston to Los Angeles

8:30 p.m.: Connecting

The last flights leave George H. W. Bush Intercontinental Airport some time between 9:00 and 10:00 p.m. The airport amenities start shutting down around 8:00. This means we’ve missed most of the finer dining opportunities available to travelers here, and I hadn’t expected to have to have gone for this long on one hot dog. In fact, I’m still scrolling down my phone gleaning bits and pieces of Lucky Dog lore, harkening back to those hours and hours ago when I first ingested that magnificent hot dog.

The hot dog carts actually have a historic status in the French Quarter. Ignatius C. Reilly, the no-luck protagonist of John Kennedy O’Toole’s Confederacy of Dunces briefly worked as a hot dog vendor for Paradise Hot Dogs, an obvious foil for Lucky Dog. The Lucky Dog stand’s place in New Orleans is so secure that the company owns the sole vending permit for the French quarter. No one else can serve food on the street. Looking up from my phone, I subconsciously yearn for a Lucky Dog stand to appear in the concourse.

Forget it, Jake. This is George Bush International.

Every plane that was scheduled to depart in the afternoon had been grounded, so we’re in the midst of a rescheduling backlog. Airport employees have gone into overtime. The line for the information desk at our gate stretches and snakes to the information desk at the gate across from us. I’m queued up with the distraught mother. The people around us are trying to get to Dallas.

Ahead of us, a statuesque blonde young man and woman look like they are in an airport-themed advertisement for Abercrombie & Fitch (If you’re going to be delayed, be distinctive). They’re going to Dallas, too, coming from college in North Carolina.

“Where are you headed?”

“L.A.”

“Soooo jell.”

Another woman falls into the impatient class. She’s upset at the woman working the desk, who she feels is intentionally stalling, as if that poor employee hasn’t been standing there all day, listening to the same angry complaints from hundreds of angry people who believe that organizing and herding masses of travelers through airports is the simplest thing in the world.

I can’t pretend that I’m somehow above it all. We’ve been in this line for an hour-and-a-half. The last flight to LAX was scheduled to leave at 8:50. We’re way past that. It’s fucking gone. And because bad weather constitutes an “act of god,” I’m going to have to fend for myself on the mean streets of Houston (OK, I’m just going to have to wait for the shuttle to the airport Marriott) and pay for the reduced-rate hotel myself. I’m just hoping that with any luck there might be a flight to Vegas, because I can hop from Vegas to Los Angeles tonight and I won’t have to sleep in Houston (no offense, Houston). I’m too tired to stand and I’m just sick of sitting. I wouldn’t even mind sleeping in the airport, but I know that I can’t. It’s not that I find the carpet uncomfortable (in fact, Houston’s carpet is pretty chic). The problem is that they never turn off the lights. It’s a compact-fluorescent Las Vegas, without the fun. Perpetual daylight with no distraction from the crushing knowledge that there is a bed someplace with a light-switch nearby. Outside the airport windows, I can see that it’s nighttime. At least in a Casino you don’t have windows. Casinos are built for forgetting. Forget time. Forget night and day. Forget debts. Forget responsibilities. In an airport, the mantra is otherwise: Remember you are at our mercy. Remember your bodily discomfort. Remember thou art in transit.

The distraught mother is telling her story to the people in line around us. Every once in a while she stops to ask me an innocuous question, like, “Do you go to the beach a lot?” Innocent questions, which I answer innocently, hoping to generate the sort of meaningless and contrived conversation that politely peters out into silence. But instead, when I say, “Yeah, I like the beach,” she comes back with, “God, I can’t wait to just wash away all of this stress with a day at the beach, and a drink. I’ll tell you, the best thing to happen to me was to get that man out of my life. The beach is the first place I went to when the divorce was finalized…”

“Uh-huh.” There’s nothing I can do. In fact, my feelings toward this woman have become increasingly frustrated. I am no longer a stranger to her. I am her involuntary traveling companion. We’ve gone through the gauntlet together and now she not only feels that she can tell me anything, but that she is going to be there by my side until the bitter end. People are starting to ask where we are going. I want to shout that there is no we or us or you two here! There is just a sad woman and a tired guy—traveling separately—who both happen to be stuck in each other’s proximity. But all I say is a softly muttered, “We’re not together,” which is a negation, a denial, a refutation which insists on itself so much that it sounds like a lie—in fact it almost sounds like I’m part of her drama, now. Other people might well assume that we have become entangled in a sordid airport affair. And in a low moment I think I get it, I understand why her husband left. I have become an airport monster, too.

That’s what time does to people. We were drawn together in a minor drama, and we coped with it by getting familiar. But try as I might to keep a good respectful emotional distance, I see that what she wants is a for real and for true friend. And as I have that thought, and look at this person, I have a second thought—a more understanding one. Maybe she wasn’t like this before. Maybe ten years of trying to hold on to a husband who might have been pulling away from her, or neglecting her, or abusing her, has left her with just enough energy to plead incessantly for love and kindness.

It’s almost my turn up at the gate. But knowing that the distraught mother and I are going to the same place, I suggest that we see if the woman at the desk can help us both out at the same time.

The woman assisting us is trying to conjure a miracle. The gate has already closed for our flight to LAX. So she checks Burbank, then she checks Vegas. She’s staring intently at her screen, and I’m doing math in my head trying to figure out if I have enough money for the Marriott’s reduced-rate room. The distraught mother doesn’t know what she’ll do. She has to work tomorrow, not in the sense that she will be fired, but because she needs to eat. I’m secretly worried that she’s going to suggest splitting a room with me, an option that I find both frightening and yet impossible to reject, since I don’t really have any money either. I’m trying to find the darkest corner I can that might suffice for a place to sleep. I’m scrolling through my phone trying to think of anyone I know in Houston (didn’t Jenny go to Rice and say she’s always happy to help? How long ago was that?).

Suddenly, the woman behind the counter says “OK,” more to herself than to us. OK can mean anything. OK, here’s your shuttle pass. OK, I’m going on break. But instead, she looks up and says, “For some reason, and I don’t know why, the 8:50 to LAX hasn’t departed. Gate B-26. Go.”

The distraught mother and I thank the woman and run down the concourse, uncertain of how far the gate is. We run past Hudson news. We run past a closed-down pretzel stand. We arrive and hurriedly show our old boarding passes to the man at the door.

“These are for a different flight,” he says.

“I know,” I reply, “but the woman at the other gate said—”

“You’ll have to go to the information desk.”

Something in my brain pops. A momentary lapse of civility that makes me snap at the man. “We JUST went to a fucking desk! She told us to get on THIS plane.” I’m suddenly one of the assholes that I’ve been judging this whole time. I freeze for a moment, say, “Okay,” and the distraught mother and I hurry to the desk.

This time, we’re lucky. No one else in line is trying to get on the LAX flight, so they allow us to go ahead. The woman prints two boarding passes and we once again return to the man at the door. I hand him my pass, which he is prepared to just systematically scan, and I try to squeeze in all of my sincerest apologies into a three second interval.

“I’m so sorry that I snapped at you earlier, sir. It’s been a long day.”

“You’re not the first,” he says, smiling. “You won’t be the last. Enjoy your flight.”

9:00 p.m.: No Man Left Behind

The distraught mother has taken a seat beside me. My phone is dead and she lets me use hers to contact my ride back home to let her know that I’m not going to spend a wild night in Houston. After I let her know, I hang up the phone and look around the plane. This is the new Southwest interior. Blue strips of light run along the ceiling above the luggage compartments, and trailing above the windows the lights are a soft-orange. Apparently, the lights are meant to “increase the sense of spaciousness.” It kind of looks like a strip club. To me, it just signals that the designer was a fan of Steve Jobs. The Jobsian design legacy is a world of softer, less jarring angles; a world of smooth curvature. The seats are much more comfortable than they were on the last flight, though there might be slightly less legroom. Above our seats, we each have a warm LED reading light.

“Good evening everyone,” says the pilot. “We understand that most of you have had a long day, and we appreciate your patience. We just want to let you know that we do technically have a green light, but there is still one last passenger trying to get back to California. His flight is stuck on the tarmac waiting for a gate to open up. Now, I know if that passenger was any one of you, you’d appreciate it if we’d wait. So we’re going to go ahead and do that. Shouldn’t be more than fifteen minutes.”

That one announcement restores my faith in humanity. To my knowledge, this airplane has no reason to wait for a wayward traveller. It runs against everything embedded into a business built in accordance with the bottom-line. People shift in their seats uncomfortably and anxiously, but nobody seems to be grumbling or groaning. There are probably people on this flight who risk missing connecting flights in LAX, but that doesn’t matter right now. Long-term repercussions are set aside for the sake of an opportunity to be sympathetic—to be human.

The distraught mother once again starts talking to me. But this time, she’s a little more excited and less sad. As am I. We both get to go home. And I know that by some time late tonight I will politely bid her farewell and never have to see her again. But I feel a little guilt about this thought, because now she’s inviting me to her house.

“Here’s my phone number. DON’T worry! I’m not hitting on you. You’re much too young for me. I’m just saying that if you’re ever in Long Beach you have a place to say.”

I take her number, and being polite, I give her mine, just inaudibly praying that she doesn’t call me, and that I don’t have to change my number. I don’t invite her to Ventura. I just tell her that if I’m ever in the area, I’ll give her a call.

What really bums me out is how much of our daily encounters are built on top of these lies and hollow promises.

Lucky Dog has an average Yelp! ranking of 3.5 stars. Reviews often feature words like “tasty,” “nourishment,” “drunk,” “overpriced,” “rubbery,” “fatty,” and “rat.” The general consensus is that it is both tradition and convenience which keeps tourists and quarter rats alike coming back for more.

Southwest Airlines has a three-star Skytrax ranking and is simply called “a low-cost airline.”

Fifteen minutes pass, then thirty, then a full forty-five before the flight attendant opens the door and a passenger comes through.

And then another.

And another.

At least eighteen people come aboard. Every seat is going to be filled. There’s still one seat left in my row and two directly behind us. The distraught mother and I see a family of four walk towards us, trying to find four seats close to each other. The distraught mother understands the desire for this family to stay within a close proximity. So she volunteers her own seat, and takes a seat a couple rows away. Now a father and his daughter sit beside me, and his wife and son sit behind us. I don’t say goodbye to the distraught mother. She doesn’t say goodbye to me. She sinks into her Kindle, and I plug in my headphones, finally doing what I had intended to do thirteen hours ago: turn on, plug in and tune out.

10:00 p.m.: Technical Malfunction

It was too good to be true. We taxied out to the runway, and again the passengers applauded. But after ten minutes or so waiting to takeoff, with no sound coming from the engines, the pilot makes another announcement:

“You’re not going to believe this folks, but I’m asking you to bear with us. We’re having trouble with the plane’s starter, and we’re going to have to head back to a gate and get a mechanic to look at it.”

This is too much for one woman at the front of the plane. “I need to go!” she shouts. “I just want to go home!” Two flight attendants rush towards where she is seated. They try to calm her down. Nearby passengers try to assure her that things will be okay. “No!” she hollers. “Get me the hell off of this plane!”

The instant we get to a gate they escort her off the plane. I have no idea how that’s going to get her home any sooner. I don’t know if it’s claustrophobia, impatience, homesickness, restlessness, anxiety or what. Each individual’s physical limit is a mystery. Whatever it was, though, she reached it. But for some reason she reminds me of Brad the Burly Redhead. She is the microscopic gas bubble that floated from 10,000 feet below that caused a blowout at the surface. In this case, unlike the Deep-Water Horizon, the situation was managed, and order was restored quickly. Tonight there will be no mutiny on the bounty. At least, not yet.

“Okay folks,” the pilot announces. “The mechanic is on board, and it looks like everything checks out. So he’s going to stay on the plane with us, and this time we really are clear for takeoff.”

I’m sure that the pilot meant to assure us that everything is going to be okay. But there’s something unsettling about flying on a plane that had trouble getting off the ground. It’s not like the mechanic can pop the hood and spray WD-40 on the starter cap at 30,000 feet.

“Also,” the pilot continues, “I’d like to let you know that there is no alcohol aboard this flight.” This announcement elicits the loudest groan I’ve heard all evening. But then he comes back on and says, “Just kidding. Alright now, let’s get this show on the road.”

11:00 p.m.: Airplane Drunk

The flight attendant had informed me just before takeoff that they don’t accept cash for drinks. So when she comes down the row with her drink cart, I ask for a coke.

“Didn’t you want a cocktail?” she inquires.

“Yeah, but I don’t have enough money on my card.”

She looks at me a second, and then repeats herself. “Do you want a cocktail?”

“Yes, please.”

They were advertising Whiskey and ginger ale on a Southwest pamphlet, so I order one of those. We cruise over the Southwest, a vast expanse of darkness punctuated intermittently by islands of golden light. Maybe Dallas. Maybe Albuquerque or Santa Fe or Tucson or Phoenix. I’m happy to look out the window whether or not there is any light below me. If I crane my neck I can peer up at the stars, though most of them are blocked by the glare of the signal light blinking on the tip of the 737’s wing. It’s all beautiful, and it’s all getting a little bit blurry. I’ve never had a drink on a plane before. And I’m now on my third.

The little girl beside me has fallen asleep in her chair. Her father is reading and taking meticulous notes. We make eye contact, and I realize that I once again will have to be social. Both of us are aware that we have to perform a cordial skit, and in this particular instance, the first communiqués are crucial. He’s been sitting beside me, clearly aware that I’ve taken full advantage of what may or may not be complimentary hard liquor (no one has charged me yet, but I’m still distinctly afraid of the possibility. I seriously don’t have money on my card to pay for the drinks. What recourse does an airline have for a guy who doesn’t pay his tab? They can’t throw me off the plane…can they?). I feel compelled to prove that I am not an alcoholic, but just someone who—under extenuating circumstances such as these—takes full advantage of that which is free, alcohol or otherwise. But I’m afraid because the only words I’ve spoken since they started serving me have been “yes, please” in response to “would you like another?” How far gone am I? How much of this delirium is from half a day spent in Boeing fuselages breathing the same recycled air and germs?

As for him, he’s wearing a Ronald Reagan t-shirt, and I don’t think he thinks it’s as funny as I think it is.

Fully cognizant of every syllable, I resolve to play the whole thing safe.

“Where are you headed?”

(So far so good.)

“Los Angeles,” he replies.

(Doing fine, Stew.)

“Is that home?”

“Uh-huh.”

I’m in the clear so far. Nothing personal. Nothing political. No drama. Just meaningless conversation between two people inside a rocket-powered aluminum can kept 30,000 feet in the air by the Bernoulli Principle and whatever magic Joe the Mechanic worked on the starter. No big deal. Still, I feel compelled to insist to him that “I don’t drink often,” and he nods in the way a person nods when he can neither verify nor discredit your claim, and yet has no reason to press the issue. He doesn’t care. All of a sudden I wonder if maybe I do drink too much. The one clear thing is that the liquor has moved my observations inward, receding from the people flying with me, gravitating towards some point in my head where I keep my insecurities; a solipsistic place. A place incubated by the forces of cabin pressure and mass transit and weather anomalies and safety concerns and the visceral human emotions that we often keep busy in order to avoid delving into, working and working and working and playing just so that we don’t have to stop and sit with all of the things that are inside of our heads.

Maybe this trip has had a toll on me. I decide it would be healthier, at the moment, to talk rather than think.

This man is not just a father. He’s a high school teacher in Fontana, near Rancho Cucamonga, Los Angeles’s region of oddly named towns. (Cucamonga has been a punch-line since Jack Benny’s old radio show—“Train leaving on track five for Anaheim, Azusa, and Cucamonga!”— as well as Bugs Bunny and The Simpsons, where Krusty the Clown assigns it on a list of funny place names for students to memorize, along with Walla Walla, Keokuk and Seattle.) He teaches history. The book is some work of historical fiction that he’s going to assign to his students. He doesn’t suspect that they’ll read it, but he still goes on annotating, preparing for class discussion. There was a time when it made him happy. He used to teach Advanced Placement history, but because of budget cuts the school cut the program. He remembers having lively and invigorating class discussions about the books that he had assigned, but now he just offers extra credit to those who actually do the reading.

“Are you at least looking forward to maybe having your own kids as students?”

“I already do,” he says. “We homeschool.”

My gut reaction is a sort of reserved understanding. As much as I appreciate public education, I can’t really debate the effectiveness of the particular school this man’s daughter may attend, the one where he has the inside scoop. But then he adds, “We disagree with the school’s values.”

By values, he means non-Christian values. By school, he means all public schools. He wants to be able to teach his children the lessons that Christ taught the disciples. My mind immediately drifts off to a very smart girl I dated in college—from Rancho Cucamonga, coincidentally—whose very religious parents homeschooled all of their children. As wonderful as she was, the debate between private, public and home schooling was a point of contention as divisive in our relationship as when a married couple decides to remodel their kitchen. The man’s eyes are drooping, but I don’t know if it’s the exhaustion of his own flight, which began someplace far off from my point of departure, or if it’s the exhaustion of twenty-five years teaching in an institution that he finds fundamentally flawed and misguided. I wonder if he feels like his whole career has been a compromise of his own values. Maybe he is one of those people who views Jesus and the Bible as so foundational to American Democracy that he is doing his students a grave disservice by teaching American History without mention of the Lord God Almighty, Jehovah.

Maybe he feels as strongly about Christ’s place in the curriculum as I do about the injustice of abstinence-only education. But this is not the conversation you delve into on an airplane. I give him a tight-lipped smile that I hope projects more disinterest than disdain. It occurs to me that we are navigating an 1,800 mile roughly east to west line across the country from Texas to California, and intersecting that line, in the five-foot space of three airline coach seats, he and I represent the vast expanse of the American ideological spectrum. In the middle, a little girl nestles her head into her father’s side, and he places his hand on her shoulder, and kisses her head. She’s in the safest and most comfortable place in the world, but she still has her own seat, her own dreams, and her own mind. When she grows up, and no longer needs a chaperone, she can always choose between the aisle and window seats.

12:00 a.m.: Going Home

When I stand up and work my way to the bathroom—waking up the little girl and once again interrupting the father’s reading—it takes a minute to find the handle (not because I’m drunk, but because this is also the first time I’ve used an airplane lavatory. Maybe partially because I am drunk). But my flight attendant/bartender watches me fumble for the handle, and she says, “We will cut you off.”

All I can do is smile. Eventually, I do make it into the bathroom and back out again, and back to my seat without incident. The glorious golden haze outside my window—enhanced by 90 proof—is the unmistakable footprint of Los Angeles. It stretches out in all directions, flat and bright, like someone tipped over all the lights of New York City and left them splayed out on the ground like incandescent legos. There aren’t any bayous winding through neighborhoods. The river is nothing more than a concrete structure speckled with street-lamps, beautiful in a sad post-apocalyptic sort of way. I remember reading in a book last semester that Los Angeles is the city most often destroyed in books, television and film. Something about it suggests the end of civilization. It’s hard to see that from the plane, and it’s even harder when knowing that the moment you land, you will be home. The distraught mother, although she does not have her daughter, will have her bed in Venice Beach. The teacher will have his middling students, his Christian values, his family. I’m not going to make it to the beach tonight, but I have a friend waiting for me, and I’m caught in this tide of inebriated elation, even though I have no idea what it means to come home. I know that that’s what this is, and something deep in the soul will always act as a beacon for home. Whatever each of us is arriving at, our quixotic odyssey has imbued us with a sense of entitlement, or desire, or yearning, to be there. But that feeling will fade faster than I want it to.

As our wheels hit the runway I expect the passengers to once again applaud the crew. I even lift my hands to join. But it doesn’t happen. Half the plane simply slept through the last moments of their journey. As the plane pulls up to the gate, the father wakes his family, and readies them to deplane, but neither of us say a word to the other. The distraught mother—my traveling companion—turns off her e-reader and sighs, but she doesn’t look back at me. Starting at the front of the plane, passengers stand, stretch, open the overhead bins—carefully, for contents may have shifted—and collect the bags they’ve stowed away. Cell phones come to life, and people whisper into their receivers acknowledgements like “I’m here,” even though, technically, we haven’t moved at all. Haven’t we been here on this plane the whole time? Whether we flew over Texas or New Mexico or Arizona or California, I had only thought of myself as on a plane, and that’s still where I am.

The wave of reanimation moves back until it reaches our row. We gather our things and start the slow impersonal procession off the plane.

1:00 a.m.: Baggage Claim

I packed a hundred pounds of books into two bags, and I’m waiting for them to shoot down the conveyor belt onto the rotating platform in front of me. The distraught mother is close by, but we don’t acknowledge each other. I wonder if I should say goodbye, or wish her luck, or smile, or wave. But I don’t actually do anything. I just don’t know the appropriate way to act towards someone for whom you suddenly know so personally, yet feel no real long-lasting personal connection to. Whatever our relationship was, it lived and died in transit.

I collect my bags first and then take an inconvenient route in order to not have to confront the distraught mother, though I do hope that things work out for her. When I step out of the baggage claim area, that’s when I feel like I’m here. In New Orleans, I stepped out of the humid summer into the controlled airport climate. I haven’t breathed outside air in thirteen hours, and the air around me is distinctly Californian, though the airport pick-up and drop-off area is like the hypoxic zone that suffocates the mouth of the Mississippi river every year. In Louisiana, it’s the nitrogen rich agricultural run-off that causes the immense low-oxygen dead zone. At LAX, the awnings and concrete structures trap the heat and smog from thousands of taxi cabs and jet exhaust. My lungs are infused with the refuse of airports.

My friend pulls up and I load my bags into the car. We drive north with the windows down. As much as I want to look around at the landscape that I’ve been away from for so long, all I can do is look up. A plane takes off over the 405 and I look at its big gleaming belly, packed full of sadness, longing, excitement, and complimentary peanuts. I wonder if anyone on that plane is feeling at all sentimental. My generation doesn’t wax sentimental about air travel. We don’t have fond memories of Frank Sinatra with his thumb out and his smile beaming on an airport tarmac in front of a TWA plane singing Come fly with me! We have heightened security alerts and delayed expectations. But my trip from New Orleans to Los Angeles will linger with me. In my backpack, I still have a pack of peanuts. In my phone, the number of a childless mother. Even my intestines continue to digest a Lucky Dog that was ingested thirteen hours and two-thousand miles ago. An accumulation of strange multitudes that can sometimes be hard to swallow.

Stewart Sinclair is from Ventura, California, where people still wear flannel un-ironically, and he is proud of that. His work has been featured in The Millions, Lent Mag, Interstitial and Nola Vie. He lives in Benshonhurst, Brooklyn and can still see the ocean just passed the highway.

Illustrations by Katherine Villeneuve