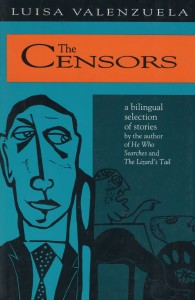

The Argentine writer Luisa Valenzuela has published more than thirty books, among which are novels, short story collections, flash fiction, and essays. Widely translated, Valenzuela is the recipient of a number of awards, including a Fulbright and a Guggenheim. She has taught at New York University and Columbia University. In 2015 she became president of PEN Argentina.

This interview was conducted in English between May 24 and June 14, 2018, in a series of phone calls, emails, and during a visit to the author’s home in Buenos Aires.

NEW ORLEANS REVIEW

What changes have you witnessed in Argentina in your lifetime?

LUISA VALENZUELA

Far too many. This is a roller coaster country, with good moments and very upsetting times like the current one, though the civic-military dictatorship was worse. But we have an incredible, almost miraculous capacity for recovery, which I hope will at some point still save us.

NOR

What can you remember of the civic-military dictatorship?

VALENZUELA

So many memories, all indelible. And they are coming back because the current elected government has decided to call upon the military to reinforce internal security, which is only threatened by the peaceful marches of people intensely worried about the astronomical cost of living. Or by women marching against male violence—a woman is killed every 32 hours in this country—and demanding legal abortion. But all I can tell you about those fateful times you may read in my books, Cambio de armas (Other Weapons), Cola de lagartija (The Lizard’s Tail), and even Novela negra con argentinos (Black Novel with Argentines). It is hard to elude writing about those terrible times.

NOR

So it gave you much to write about. Do you think hard times fuel creativity?

VALENZUELA

Let me separate this question in two. No, I don’t think that hard times necessarily fuel creativity. Often it silences you. Freud knew that very well. I had this ongoing discussion with Joseph Brodsky at the New York Institute for the Humanities; he used to affirm that censorship is good for literature but bad for the writer. But at home it could be seriously bad not only for the writer (who finally takes responsibility for his or her words) but also for everyone around us, even innocent people who appeared in our phone books.

And, on the other hand, I did write a lot during those terrible times. But I was one of the very few, and it all started before the military takeover. The Triple A (Argentine Anticommunist Association) under the leadership of José López Rega, Minister of Social Wellbeing (Bienestar Social) triggered the most irrational state terrorism, which inspired my book of spontaneous short stories, Aquí pasan cosas raras (Strange Things Happen Here). Things were already cooking then. Como en la Guerra (He Who Searches) was published, taking a risk under the dictatorship, but was written before that. Premonition? Of sorts. Horror was already in the air, ever since the late sixties, as you may read in my novel Cuidado con el tigre (Beware of the Tiger), written in 1966 but which I dared publish only in 2011.

NOR

Growing up in the household you did, was there any way you could have not become a writer?

VALENZUELA

There were practically all the ways not to. It was an overdose of writers around me, beginning with my mother, Luisa Mercedes Levinson, and all her friends and colleagues. I was a voracious reader and from a very early age attended their talks, but I wanted to become anything—mathematician, explorer—other than a writer.

NOR

So did you attempt to pursue an alternative career?

VALENZUELA

Oh yes, I wanted to be an explorer, an adventurer; or study a variety of subjects such as mathematics and physics that really attracted me. I was, and still am, omnivorous and knowledge excites me to such an extent that it makes a choice impossible. Wanting to be everywhere and learn everything, journalism seemed the best, or perhaps easiest, option. There were no real schools of journalism then, so I went head first into the practice. Of course, I had a rich background of lectures and readings and so on.

NOR

Were you encouraged by your mother to write?

VALENZUELA

My mother was a well-known writer at the time, so she knew what kind of life being a writer meant and did not encourage me at all. At least, not to write literature. She sent me to a private British school saying she wanted me to do sports and not become a “greasy intellectual.” Journalism, though, was okay; she considered it a minor form, and in a way, she was right. But I did not enjoy it and ended up writing fiction in spite of her. And married a Frenchman, went to live in France at twenty, and in a way left all that behind and wrote my first novel, Hay que sonreír (Clara), while there.

NOR

Did you see much of Jorge Luis Borges, Julio Cortázar, and other literary figures growing up? What impression have they left on you?

VALENZUELA

I did see Borges often, and so many other intellectuals of great value, fiction writers, essayists and publishers and poets. My mother had some sort of informal literary salon, and they gathered often at our home, so since my early teens, even before, I would listen, fascinated by their debates and talks, but I found them excessively passive. That was not for me, just food for the mind. At one point, Borges (“Georgie,” at the time) and my mother wrote a short story together, “La hermana de Eloísa” (“The Sister of Eloisa”). It was meant to be an obnoxious story, and they both laughed so much that probably I thought story writing was joyful. Which it is, because even if you deal with the darkest of subject matters, the immersion in language is always elating. Cortázar, on the other hand, whom I admire deeply, I met much later in my life.

NOR

Do you think seeing writers from a young age gave you a different perspective on what makes a good writer? There’s a growing tendency, for example, to associate the writer with a certain charisma, eloquence and wit, but I know you’ve said Borges was shy and didn’t necessarily stand out from the crowd.

VALENZUELA

Charisma has nothing to do with the equation. What I learned then was to be natural and even irreverent around writers. No respect as such, only for their talent, in a casual manner. And yes, Borges was very shy and ironic and somewhat self-absorbed. His colleagues admired his writing, of course, but said he was a writer for writers, that the common reader would never understand him.

NOR

What do you think about the American writing scene that encourages open mics, participation in writing workshops and other activities that might cause anxiety in the quiet or timorous writer?

VALENZUELA

It’s not only an American scene nowadays. Here in Argentina there are many private and public workshops, lectures, readings and other activities that may or may not cause anxiety in a writer. Writers have to earn a living, and it’s not easy to do so with our books, so all these other literary activities help a lot. Of course, there are many shy writers who do not like to speak in public. And there are others who love it, even to excess. But writing is a solitary job, so one needs at some point to be secluded. You do have to go out at times, though, and perhaps promote a new book—that means a launch party, getting in touch with your public in lectures at universities and in places where you can have a dialogue with readers.

NOR

Which other Argentine and Latin American writers do you appreciate? Or writers from farther afield?

VALENZUELA

Oh, the list is vast, a movable feast if we may say so. Cortázar is the one who is closest to my way of understanding the act of writing. And nearer to my heart. I admire Carlos Fuentes on the opposite extreme of the equation. That is why I wrote a book on both of them, Entrecruzamientos: Cortázar/Fuentes (Crossings: Cortázar/Fuentes). It is astonishing to discover how much they connect in their so different personalities. But if you ask me for a list, it can go from Clarice Lispector to Haruki Murakami, with innumerable names on the way.

NOR

You mentioned you started out as a journalist—you worked for Radio Belgrano, El Hogar, and later for La Nación and Crisis magazine, among others. Do you think journalism is that different from fiction? Did you enjoy telling other people’s stories?

VALENZUELA

Already at eighteen, I wrote my first short story, “City of the Unknown,” which still exists in translation. But from the very beginning, I knew that journalism and fiction travel on very different rails. And I wasn’t necessarily telling other people’s stories for the papers but doing full-fledged journalism, in the streets, on journeys, and of course interviews, but that’s a different matter. And later as a columnist, offering opinion and analysis of the news, the sort of journalism that forces you to be very close to facts.

NOR

To what extent is journalism, as your mother believed, a minor form in comparison to fiction?

VALENZUELA

My mother believed strongly in intuition. She thought intuition was the way of accessing profound poetic thinking. She would often repeat that I was too intelligent to be a good writer; she thought intelligence wasn’t something that had to be at work when creating literature. I don’t agree; I think you need a blend of intelligence and intuition. But in journalism you cannot allow a flight of fantasy. And probably my mother was thinking of journalism as simple reporting. A reporter has to be very factual. Of course, New Journalism relies on intuition, and we have something called Performative Journalism, and great non-fiction books are published—the Truman Capote kind of journalism. On the shadowy side of this story, I remember the case, many years ago, of a very bright journalist who was kicked out of The New Yorker when he cheerfully admitted that he sometimes changed the locations where his interviews took place to give them a more interesting background. Reality in excess was the old-fashioned way of seeing journalism; it killed whatever poetic insight you could have.

NOR

What about telling your own story, as in Dark Desires and the Others, where you recount your own experience of living in New York for a decade? What was that like?

VALENZUELA

Again, it was a different matter because I didn’t sit down to write about my New York experience but simply was talked into using my diaries of the time, which were extremely personal and emotional, not at all factual in the sense of telling my comings and goings.

NOR

How is it different to be a woman in New York compared to being a woman in Argentina, where there is still a culture of machismo?

VALENZUELA

The difference is that machismo here is out in the open, whereas it is subtle and under cover in the States. There I learned a lot about those nuances.

NOR

And how does Argentine feminism differ in its objectives and its methods to its American counterpart?

VALENZUELA

Well, feminism in the States was overpowering during the eighties, while it was quite isolated here. But now the scale has flipped, and it is important to point out that finally, here in Argentina, women’s struggles are intense and out in the open and that force is taking over the streets in a very courageous and powerful way, as you might have well experienced.

NOR

Yes. At present Argentine women are marching for their right to legal abortions—through the referendum tomorrow. Do you think that it will happen here?

VALENZUELA

I think they will vote for the law. By a very narrow margin, but they will. I think the government, even if shamelessly rightist, is interested in getting this law passed as it is a distraction from the current horrible economic situation they’ve got the country in. What is absolutely fantastic here is the power of the women’s movement—the fight is very intense at this point. But we do have a history of courageous and combative women; think of the mothers and the abuelas of Plaza de Mayo. And now the young people are really joining in the demands; it is moving and very heartwarming. I hope that the senators will vote in favor because of all the lives lost from women doing illegal and very unsafe abortions. So what kind of life are they defending, those against legal abortion who call themselves pro-lifers? We should be defending the lives of women in general, including those who cannot afford a child. I am president of PEN Argentina, and PEN defends all liberties for women, the essence of freedom of expression.

NOR

I’m asking for many comparisons, but what differences do you notice between the Latin American and North American literary worlds?

VALENZUELA

We have a completely different approach to the act of writing, and we are intense about reading between the lines. It was fascinating to compare both approaches while teaching creative writing in English.

NOR

You taught creative writing at New York University. Do you think creative writing can be taught?

VALENZUELA

At Columbia, I just taught Latin American Literature for Beginners. Only NYU finally tempted me to try something I thought was out of my reach when it offered me the Berg Chair for a semester, by the end of which they decided to keep me on. So I can now say that writing cannot be taught, no, but stimulated, yes.

NOR

How do you recognize emerging talent in creative writing classes?

VALENZUELA

Oh, it is not hard to discover those who have a real, deep feeling for language, not just a talent for telling stories.

NOR

Where do your ideas for stories come from?

VALENZUELA

Good question. That is a mystery that keeps you going, from one surprise to the next. Which is my way of writing, without a prepared plot or anything.

NOR

Where and when do you write?

VALENZUELA

Anywhere, anytime, when I manage the connection with that creative part of the self which we ignore.

NOR

Do you enjoy rereading your own work?

VALENZUELA

Yes, when I am forced to; otherwise I don’t. But when perchance I do, I usually find that I was a much better writer at that time.

NOR

Do you still feel you have a lot to say?

VALENZUELA

I never felt I had anything to say. Just the curiosity to explore….

Elizabeth Sulis Kim was born in Bath, England. She holds an MA (Hons) in Modern Languages from the University of Edinburgh and currently works as a freelance journalist. She has written for publications in the United Kingdom, South Korea, and the United States including The Guardian, Positive News, The Pool, HUCK, and The Millions. She currently lives between London and Buenos Aires.