{from Issue 37.1}

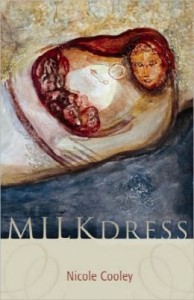

Milk Dress, by Nicole Cooley. Alice James Books, 2010. $15.95, 96 pages.

Nicole Cooley’s third book, Breach, beautifully and deliberately described the period of extended grief following Hurricane Katrina. For a native of New Orleans living in New York, there were a series of tragedies to be worked through: the hurricane and the subsequent failure of the levees, the poet’s heartbreaking attempts to reach her parents after the storm, the morning of September 11, and a grown woman’s wish to keep her family safe from what she had no power to control. Cooley’s latest collection, Milk Dress, retains the sustained pathos of her earlier work but the poet locates these poems more in relationship than in current events. In Milk Dress, we see the poet navigating the transformative identities of pregnancy, childbirth, and motherhood. However, it is clear from the first page that this poet is not one who has forgotten the dangers of our time, nor is she willing to sentimentalize family life as distinct from those dangers. In fact, the prefatory poem that opens the collection very much connects family life to national tragedy.

This first poem, “Homeland Security,” sets the tone of the book in subject and strategy, beginning, “Write against narrative: here is the television’s blue / square of light, milk needling my skin.” A few couplets later, the lines shift toward something more sentimental: “Write toward the girl, asleep beside me, her body / made of mine.” That Cooley combines the imagistic and the sentimental should be no surprise to those familiar with her work, nor should they be surprised by the frankness of these poems. To some, Milk Dress may seem less poetical and more journalistic, while to others the book will seem more precisely literary and metaphorical, and both are to some extent true. For my taste, I enjoy Cooley’s ability to mix the mundane and the metaphorical, as it allows her the emotional space to confront her questions more directly.

I am always intrigued by the layout of an Alice James Books publication, because they seem to give a great deal of creative freedom to their poets. Cooley presents Milk Dress almost as a single meditation, broken up only by italicized interludes that often refer to Harry Harlow’s “Nature vs. Nurture” experiments with infant monkeys. A curious strategy, certainly, but I was happy to see a change of pace from the standard preface-and-four-section layout of most contemporary collections. This plays very well into Cooley’s mastery of the found text: While these poems are ostensibly about pregnancy, childbirth, and family, the less obvious subtext is one of perceptions and ways of seeing. A favorite poem in the collection (“Pregnant at the Archive”) has the speaker thumbing through prints by Mary Cassatt, seated in a chair not made for a pregnant woman, and thoughtfully finding meaning in the interstices of art and motherhood: “All the conflicting voices. The body backlit. / The body incidental. The body reprised.” This is the eye of one who sees herself as part of her setting as much as she questions the fixity of setting altogether. This is also the mind of one who traverses the mysteries, doubts, and uncertainties of tragedy by being attentive to it both directly and peripherally, and who finds its traces in what may seems commonplace, quaint, or quotidian.

Nicole Cooley is political without being preachy and deftly poetical without being clever. While her Breach remains a favorite book of mine, and perhaps singular in those works attending to post-Katrina America, the new collection Milk Dress shows similar emotional and intellectual depth, while still retaining a thoughtful attention to form and craft.